Akinori Oishi (Japonska) – portrait, Stripburger 65, Maj 2015

This issue of Stripburger features a Japanese artist, illustrator, designer and sometimes even comics artist Akinori Oishi and his always happy face. Aki’s tiny and constantly smiling characters appear in magazines, newspapers and books, they conquer shop windows, gallery walls, even building facades, they follow him to artistic residences and strut as mascots at different festivals while starring in ads, animations, interactive projects and on the internet. We wanted to know if his smile (as well as his characters’ smiles) ever turns into a frown. Aki insists it doesn’t. Let’s see if this is at all possible. [Tanja Skale, Kaja Avberšek & Katerina Mirović]

Interesting. Comics represent the smallest part of Aki’s artistic endeavours. While growing up in Japan he was surrounded by the hugely popular mangas (it seems that the stereotype of mangas occupying almost all aspects of Japan’s popular culture is not overrated) and wanted to become a professional manga artist (as well as a professional football player!). However, with the discovery of European children’s books, a whole new world opened up and captured his imagination. Of course, he did not understand the stories, but he was drawn to them by the exotic images. He had never been an avid reader and art never played a great role in his family. As a teenager he discovered MTV and decided to become dedicated to the art of animation. In the 1990s only a handful of schools in Japan offered the opportunity for a budding artist to learn about new media and animation, thus he studied painting at the Kyoto City University of Arts. “Only paintbrushes and oil based paints! No computers! They expected us to create monumental conceptual works, but I was interested in everything else but that!”

During his studies he discovered alternative French, German and American comics, became fascinated with the legendary Japanese comics magazine Garo and admired artists such as Yoshiharu Tsuge, Hironori Kikuchi, Suzy Amakane and Shingo Iguchi who published their comics there.

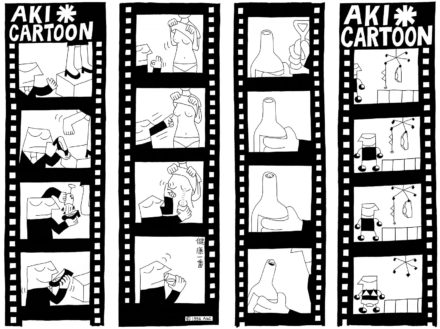

This led to the attempts of creating his own alternative comics. “I’ve asked a few professionals what they think about my comics. Most of them shared the same thoughts: they enjoyed the drawing, but thought that the story lagged behind. Personally I still think I’m not good at telling stories, thus I’ve decided to focus on the visual language, the drawing itself.”

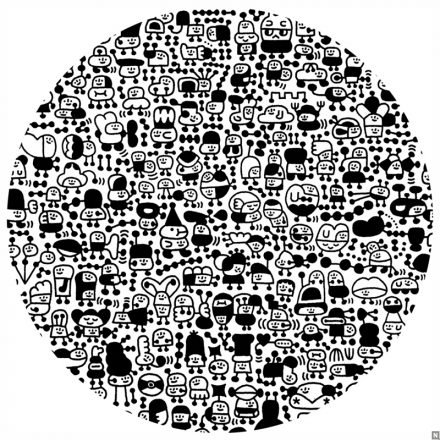

Indeed, while tracing the development of Aki’s visual style, one notices an increasing minimalism and streamlined stylization, both of characters and background. His drawings are small, yet complex and meticulously orchestrated universes that seem to have neither beginning nor end. However, they have rhythm. Characters form chains and patterns; they grow like living organisms that can occupy any open surface. Quite literally: within his creative process Aki is led by form, shape and composition, rather than story, content and message. “I start with two dots and two lines. Eyes, nose and smiling lips. Then I add a little here and a little there and an interesting figure suddenly appears in front of me. That’s all! That’s my daily exercise!” Finally, we realize that Aki’s characters are shapes that come alive only when the reader gives them character.

However, let’s return to storytelling: something has to eventually happen to his characters … “I like to use slightly abstract and simple jokes in my short comic stories. I love simple and adorable humour, typical of the French film director Jacques Tati. I admire the way he uses pantomime, the universal language that leaves plenty to the imagination. I like it when readers use their imagination to interpret my stories and characters. You might find one of my characters erotic, even though I don’t. Meaning is born in the eye of the beholder. It’s interesting to hear what people see in my characters. Their interpretations are a source of great inspiration. They might get the character totally wrong, but through mistakes new things are born!”

We were introduced to Aki and his work in 2006 when we published two of his one-pagers in Stripburger

#44. “At the time I was trying out a new recipe: a short story with a hint of adorable humour, served on drawn-out frames. It worked!” We wondered how did he discover and find us. He replied that he doesn’t remember, maybe it was Stripburger that found him … “Slovenia was outside of my interest zone at that time, he he … But I was in touch with the publishers of the Swiss Strapazin magazine, I had friends in the Moga Mobo collective in Berlin … maybe this is how I came across you.”

Aki says that his tiny drawings are fuelled by great imagination. It all starts on the micro level.

As you enter his website (aki-air.com), four of his mini-men appear on a washed-out blue background. They’re dancing within a small white square, obviously pulsating to the rhythm of electronic music. A click on the square takes you to a black page with twenty small squares on top: these are Aki’s so-called “micro-movies” that almost need to be viewed through a magnifying glass … At first glance one could say that Aki is a man of micro things. At the same time, a huge “macro” can grow from a “micro”, as, for example, was the case with the huge mural that he made for a building facade in Taiwan. Size matters, but it also depends on the perspective and the point of view. Micro can be macro and vice versa.

At this point the great Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama comes to mind, for she deals with micro and macro universes, patterns, dots and especially infinity in her own particular way. She says that “The universe contains infinite dots. Stars are dots. Everything starts with a dot. I’m a dot, you’re a dot, we’re all dots.” So what does Aki think about her art? He points out that all that their visual languages have in common is that they are Japanese, and the Japanese love details. “Yayoi’s art is totally different from mine. I think that her motivation comes from within; her art is born out of frustration or trauma. Maybe it’s about her hallucinations, maybe she’s visualizing her emotions, fear and stress … on the other hand, I draw from typography, not from my inner world or my emotional state. When I draw, I simply look for patterns, shapes and lines. My characters that form patterns are merely shapes. No feelings, nothing spiritual. The most important part is enjoying the drawing process. If I drew from my interior motivations, fear or sadness, my work wouldn’t have been so joyous. My observation is that female perspectives generally stem from interior motivations, while male come from exterior ones.” Ok, now we get it.

Aki’s mini-creatures that tend to hang together are always smiling. Happiness is the only emotion they know and choose to show. In the same way as his many creatures form a pattern, their smiles also form a pattern, a tapestry that conveys no emotions, a tapestry that just IS. Aki confesses that their smiles were inspired by the smiling Lego figurines from the 1980s. At the time he could not get hold of Lego building blocks, thus they became even more desirable. When Aki seriously started dealing with typography, their smiles meaningfully complemented the different typographical elements and this is how typographical smiling patterns came to be.

“My main message is optimism. The duty of the artist is to never give up even when this seems impossible.

When someone is sad, they can’t go on. A smile is the best way to overcome stress. When I’m tired in the morning because I slept for only two hours, I try to convince myself that I’m OK. Smiling helps with self-control. I smile, I’m not tired, everything’s OK, I can continue. Life has taught me that smiling is like therapy: it always has a positive effect. It’s like a virus that spreads and gives hope. My childhood was not that happy. I wasn’t very tall or confident, but my heroes were all great sportsmen. Now it’s different: I’m an international artist and when I’m invited to a festival I’m seen as some sort of a hero! I believe in my abilities!”

Aki fills his sketchbooks like a madman and says that each and every one of them is a trip in itself. We wondered if he enters a special state of mind while drawing, some sort of a trance without taking any drugs. We also know that he loves to travel, not only within the universes in his head, but also physically (although he’s unwilling to discuss anything personal and constantly tries to obscure the meaning of his words). Aki’s drawing process (rhythm, repetition) is almost like meditation, like creating a mandala that doesn’t get destroyed afterwards. It is like therapy for the mania, obsession or addiction … to drawing. He even gave himself the nickname “Drawaholic” and the addiction is compulsive per se. During the interview we realized that Aki balances this peculiar compulsiveness with discipline, routine and perseverance. So how does he spend his “normal” day? During the day he is a husband, father and housekeeper. His time comes only after ten o’clock, when the rest of the family is asleep. He stays up and draws until two or three o’clock in the morning …

It’s impossible not to notice Aki’s regular Facebook activity and his smartphone snapshots of his wee lil’ men in different situations from Aki’s supposedly banal everyday life. They seem to be very outgoing, curious about the world and attention-seekers … “I find inspiration for my work in everyday tasks. I’m in the kitchen, holding an apple. I say to myself: This apple is really beautiful! I’ll put my wee lil’ man figurine next to it and take a photo of them. When I’m hanging the laundry, I see the sky and I watch it change. Then I take a photo of it together with my wee lil’ man! During the weekends I usually take my son to the park. While the children are playing I’m bored. I see a flower, I draw a lil’ man, I put him next to the flower and take their photo: art is everywhere! I always try to stay positive. In the beginning it was hard to find time for my artwork as I had so much housework to do. Then I realized I just needed to shift my perception and find a new way of dealing with all this. I figured out that my sketchbook is all I need: it only takes a few minutes to draw a tiny drawing.

I consider it vitally important to continuously post photos of my mini-interventions on Facebook and Instagram. This is how I prove to the world and myself that I’ll never stop making art.”

Aki has also worked for big studios. His master’s degree from the IAMAS international academy in Gifu (where he studied animation techniques and multimedia in general) opened numerous doors for him. The academy encouraged participation in international competitions, and Aki’s works were well accepted in various international multimedia fairs, such as MILIA in Cannes where he received the young talent award in 2001. This led to the invitation to work for the French giant studio Teamchman, which he gladly accepted as he always wanted to work outside of Japan. He designed videogames, animations and trailers for Canal+, worked in advertising for Coca-Cola, Nivea, etc. “That was a great career. But then the economic crisis struck and I was forced to look for work elsewhere. I was a visiting professor at ECAL, University of Art and Design in Lausanne, Switzerland, where I taught animation, then I lectured at the Tama University in Tokyo … all of this is in the past now. Now I’m a freelance artist.” Would you accept Disney’s or Coca-Cola’s offer to work for them as a “freelance artist”? “Sure! That would be a great opportunity. But I’d have to be cautious, for this could be very disruptive. If my character was chosen as a mascot, I’d become hugely popular and that wouldn’t be me anymore … I think the author has to stand for the character, not the company. Well, but I could sure do with the money!”

Aki admits that it’s not easy being a freelance artist, even in hi-tech Japan. Many artists have other jobs so that they can pay the bills and these jobs often consume all of their energy that could be used to make art. “In this sense I’m doing quite well. It also helps that I’m not the sole breadwinner in the family.”

Our next question dealt with his artistic residency in MGLC, Ljubljana, where he spent eight weeks in late autumn and during which he also appeared as a jury member at the international animation festival Animateka. During his stay he also presented his works in exhibitions in Kinodvor, Slovenska kinoteka (Ljubljana), Udarnik (Maribor) and placed cut-outs of his characters in many window-shops throughout Ljubljana.

When the happy-go-lucky Aki arrived to Ljubljana, the city was covered in fog and he felt blind. Eventually he became used to the fog and was able to see through it. He even named one of his characters Friendly Fog – we wonder why? Then there are Mr. Triglav (inspired by the highest mountain in Slovenia and the eminent national symbol), Mr. Zmaj (the dragon which is the symbol of the city of Ljubljana) and other characters that appeared on the Ljubljana Castle, on city busses, on our diligent Carinthian bee … “I knew nothing about Slovenia which is why I thought it had the potential to be interesting. When I think of Italy, I think of Ferraris and football, with France I think of Versailles, but Slovenia was a blank sheet of paper. Just like my sketchbook before I start using it – in two months I’ve filled both, Slovenia and the sketchbook, with my characters.”

He stated that such a long stay was necessary for his creative process. “I need a lot of time to get used to the environment and start enjoying it. Only then can I start enjoying the creative process, which results in a happy art piece. I’m happy that I was able to give away my smiles to the Slovenian people from whom I’ve received nothing but positive responses. I sensed that my art fits the current Slovenian situation perfectly. The economic crisis is still present and the people are unhappy. That’s the reason they need external stimuli even more than normally – to see the world in a brighter light!” Dear Aki, if only it was that simple!

Last but not least, the most obvious and essential question: what are his plans for the future and what is he looking forward to? His desire is to travel some more, discover new places, meet new people and create new characters. He points out that the continuity of artistic activity is of utmost importance to him, but he’d also love to work on bigger and more ambitious commercial projects, earn more and become more popular. He’d like to penetrate the American market where he could combine art and business even more efficiently. “But I still think that the artist should be more important than the audience.”

Inconsistencies notwithstanding, Aki will continue to spread the seeds of joy around the world. And boy did he make us happy with his first-person comic story about his artistic residence in our little city. So kawaii!