Ciril Horjak a.k.a. Dr. Horowitz (Slovenia) – interview, Stripburger 63, April 2014

Dr. Horowitz, as Ciril Horjak calls himself, is a unique phenomenon in the Slovenian cultural space. He flies unrestrainedly from project to project, he is an active member of society who lectures on comics, participates in the Risanka [cartoon, translator’s note] radio broadcast, while at the same time regularly taking care of comic strips and illustrations in the newspaper Večer, his four children and probably many other things. His life is impossible to keep track of and his blog is always out of date. Therefore, it is a real treat when you meet him somewhere in Ljubljana and in five minutes he tells you about at least ten new things that he has read or seen since your last encounter. Therefore, the interview with him is necessarily more substantial than the regular interviews in Stripburger; to do them justice, his stories would necessitate a whole book.

Even though he lives in Ljubljana, it is difficult to meet with him in person. His answering machine tells you that you’d better not even try, as he is busy with various projects until the end of 2014.

So, taking things in his own hands, Domen Finžgar interrogated him over Skype.

As usual, we start with some general, introductory questions. Which comics influenced you the most?

I was heavily influenced by a collection of Disney co-mics from the thirties, which was reprinted by Politikin Zabavnik in the late eighties. These reprints were amazing. They obviously must have had the original art as well, the films or something like that, because the comics were printed in such a way that they felt very similar to those of the thirties. The collection consists mostly of old, wonderfully drawn Disney comics. If I put aside all the controversial issues associated with this corporation, I was able to admire the very refined drawing of early Disney. It is as if the reader has found himself in a time machine!

Can you still find any time to read comics these days? Do you follow comic novelties?

Yes. Thanks to mobile phones with larger screens, which have brought about a possibilities for reading comics. These days you can carry comics in your pocket again as well as buy them at a very low price, just a few cents. In America at around 1880 they reduced the tax on newspapers, resulting in them becoming cheap, which in turn made newspaper comics extremely accessible. Now, a similar revolution is taking place. Minimal prices such as 50 cents for a digital comic – despite my previously mentioned affection for old, fragrant prints on beautiful paper – enable something entirely new. These comics are reproduced at high resolution, individual frames can be greatly magnified to observe the details. It brings about a new quality of reading.

Currently I’m reading something that I previously found very foreign – American superhero comics. It is still a genre that is not to my taste, somehow it just doesn’t do it for me. But I regard such reading as my homework. I’ve read the early Hulk comics, early Batman… Superman was a true revelation for me. In the early editions, Superman was an advocate of trade unions and an opponent of capitalist exploitation, although at the same time he advocated the so-called ‘American dream’. The early Superman was naive and was able to fix things from within the capitalist paradigm using violent action. If that were in fact possible, he would make an ideal bank supervisor! In contemporary movies, instead of addressing bank malfeasances, he chases after crooks. But in the old days he used to leave the crooks to the police officers and focus instead on installing order in conference rooms.

You’ve always been considered to be an advocate of new technologies; you were one of the first cartoonists in Slovenia to change their brush and ink for a digital pen. Your artistic name is Dr. Horowitz. Is it true that the ‘doctor’ part of your nickname stands for your expertise in Photoshop?

True. I’ve been nicknamed ‘doctor’ by my colleagues at Ljudmila [digital media lab, translator’s note], just because I had – and still have – a good command of this software environment. For example, even when my creations are transmitted live on television, I withdraw all the tools and toolbars from the screen, as all the shortcuts are at my fingertips. Probably another reason why I am so good at handling Photoshop is due the fact that I once used to teach it professionally; at that time, I must humbly admit, many a student of mine had a much better grasp of it than me. I guess I was the one who learned the most from those lectures.

Your earlier comics were much more punchy and radical (for example, your works seen in Stripbur-ger and in the collective Grejpfrut). What has convinced you to take the edge off your drawing? It seems that your ideas are still sufficiently critical and controversial (especially in your illustrations for Večer newspaper), but they seem to be wrapped in a milder image. Do you find this a more effective way of presenting ideas?

The change of my work mode was conscious. Firstly due to the economic situation. At some point, comics were suddenly expected to bring me a regular monthly income. By comparison, Miki Muster, along with his wife, was able to pay off his house in four years, while I am currently in the middle of paying back a twelve-year loan for a much smaller apartment. At that time, financial conditions were better, whereas today a cartoonist must draw on a significantly larger output in order to survive. The second reason is that I see a big need for comics to support education processes.

You are saying that I used to be more radical? Two weeks ago I drew for Afghan immigrants in Slovenia at the invitation of trade unions. My drawing was used to explain how the labour market in Slovenia works. In the future I would like to make my comics even more clear and clean. The comic I am currently working on [graduate comic strip, editor’s note] discusses processes in dentistry. My mentor was completely taken over by the drawing, as it required a lot of hard work and concentration. One can very easily hide behind some kind of artiness. However, this is not meant as criticism of artiness the thing is, when you draw a comic, which you want to make understandable to anyone, you get used to expressing yourself clearly through constant adaptation and testing.

At a global scale, cartoonists producing educational comic strips are rare; in Slovenia, you are supposedly the only one. On the other hand, it appears that providing information in comic strip form is becoming part of everyday life (such as safety instructions on airplanes). How did you end up in this interesting comic strip niche?

I’ve always been a bit of a pedagogue. I am extroverted, I like talking, learning and teaching. First of all, I worked on educational comic strips along with a co-worker in DZS [National Slovenian Publishing House, translator’s note]. It was a motivational internal newsletter in comic strip form, with which we wanted to motivate DZS employees to have a better attitude towards their customers and colleagues. These motivational comic strips had a critical note from the very outset. We visited various locations and criticised the consequences of the restructuring that took place within DZS following the transition [from national to public, translator’s note]. The Director never supported this comic strip idea. On the other hand, the company bonded.

Communication began where it had not previously existed. In fact, with such projects it is not only about the comic itself, but also about the process in which it is created. It involved many people and stories.

I very much appreciate your enthusiasm for life-long learning, as I believe it the only way to develop as an artist. Is there any area that you are particularly interested in? Does this knowledge represent a kind of pool from which you draw ideas for your work?

I am extremely interested in theory. All kinds. From physics to the theory of language. The news that excited me most in recent times was the discovery made by Neil Cohn from TUFTS University. The study proved what I had been claiming all along. Namely, that the comics are a genre of literature, a type of language. This is what I had been teaching for several years as a guest lecturer with prof. Andrej Blatnik. Neil Cohn connected devices which detect brain activity to the heads of comics readers, faced them with a variety of comics (structured differently and of varying quality) and proved that the brain processes taking place when reading comics were the same as those connected with reading a text or speaking one’s mother tongue. This discovery turns a new leaf in comics theory. Comics are a medium with an extremely interesting past and an even more exciting future.

I suppose there was a connection between your exploration of educational comics and your later desire to help marginalised people to integrate into society. What can you do to facilitate the inclusion of such people back into society?

Due to family and financial obligations, I am currently working less in the field of helping people with disabilities than I would want to be. Unfortunately, Slovenia is too rigid with regard to work in the field of disability; even when I had more time, my colleagues and I were unable to achieve significant changes. We made small and slow changes. In spite of my efforts at that time, nothing happened in this area at the organisational and governmental level. I am one of a few isolated agents; we do not have a common platform. I do not speak about it at conferences, I do not write articles. Status quo.

Currently my work in this area is limited to weekly vi-sits from a boy with an autistic spectrum disorder, who comes to colour my comics. It’s great that these comics get published. On the other hand, there is also a lot of teaching, individual creative work, which is perhaps even more interesting, but does not get published since the activity is for his development.

In general, when working with people with disabilities, the thing to bear in mind is the visualisation of structures. Making a process or a task – or whatever else – visible. This works miracles with people. There are certain regulations of how a process is visualised. Will Eisner, for example, during World War II, drew instructions on how to repair jeeps; people with autism need a comic that shows them how to perform basic daily tasks.

There are people who do not read comics. Some people of average or even above-average intelligence cannot grasp the comic as an effective medium.

Are you referring to what is called ‘visual literacy’?

I guess this is not merely a matter of visual literacy, but also about the functioning of the brain. In short, it is not merely a cultural issue, it can also be quite physical.

You are not afraid of collaborations with other artists (such as scriptwriter Andrej Rozman – Roza). Do you prefer working on your own or in collaboration?

I prefer collaboration. Currently I have developed a very clear, generic style of education and I would need a drawer who could be taught this style. Unfortunately, there is a shortage of comics drawers in Slovenia. Probably because it is easier to make money in other areas for the same amount of work. I have too few co-workers.

You are very socially active. In Slovenia, you can be seen in action on almost every current issue, manifestation. Most recently, I saw you in a documentary film about neo-Nazis in Slovenia. I wonder in what way you feel it your duty as a human being to draw attention to social problems and how you look on such issues as a comic artist?

At the time of the shooting of the film, Siniša Gačič [one of the makers of the said documentary film, editor’s note] reproached me for being naive. That was because my position then was that neo-Nazis are people with rights too, as every other citizen, and that in order to eliminate the problem caused by them, it is necessary to engage in dialogue with them. When you reconsider the problem soberly, you see that this claim is not naive. If we fail to establish a dialogue, if we refuse to dare to think about controversial topics, these issues will imprison us. (“If you do not catch the beast, the beast will catch you.” – Moby Dick). I think it important for me to engage as much as possible with trying to solve social problems in the time that I have at my disposal.

As for comics and social criticism, it’s not the comics’ job. A comics artist is just a man with a tool. Little Nemo in Slumberland does not talk about current affairs. You could even say that he employs a slightly colonial discourse. However, comics are also drawn by people who themselves originate from socially problematic environments, from distress (such as, for example, the authors of Superman). In these comics one often feels a social element in the story. A comics artist is a man with a tool, while it is the social context and the artist’s own decision that leads to the result.

How can you continuously engage in social criticism and at the same time take care of regular income? Do you choose which companies you cooperate with?

Very carefully. Also an associate within the firm, rather than just the company itself, needs to be adequate. The team with whom I work must be okay. It’s also important that the company offers their employees a good rapport in the workplace. It is logical that every company will also have some disputed points, but if my comics can be co-responsible for changes for the better, then it is possible to collaborate. But I would not work with just any company.

If properly used, comics can bring profits to a company. If they are used for internal communication and/or education, they can help reduce costs. So there is an economic reason, while at the same time it’s a fun way to work, even on serious projects. If people in a company do not recognise this fact, it is impossible to work with them.

In a way, you’re a very stereotypical comics artist. You’ve got your anthropomorphic mouse (named Mišima), and at the same time you have your own autobiographical character. The latter is more confident than yourself; he is even more direct, entertaining, one who takes matters into his own hands. Why are we cartoonists so fond of anthropomorphic animals and why do we portray ourselves as different from what we are really like?

Comics drawing is like a screwdriver. You “screw something on” and “screw something off”, make some changes. I draw myself differently in the desire to become such. And in fact, one does change oneself through comics. When you finish drawing a comic, at the end of the process there is a little change; your colleagues have changed – and, not least, your readers have changed. It is a powerful tool.

Anthropomorphic animals have the property of being slightly removed from the similarity to a real person. Therefore, both young and old people can identify with them. They function as a large container of water in which many people can see their reflections. Even cats could read comics with anthropomorphic animals and be able to grasp their point [laughs].

On the other hand, your departure from the comics stereotype is that you never had problems in establishing contact with people, not least in the business world. You are busy with various projects until the end of 2014. How do you do it?

I am definitely gaining some mileage in the business world; after all, I will soon be turning forty. Unfortunately, the Slovenian market is small; the culture is also somewhat specific; people are more cautious, less prone to risk. I have a desire to work, enough talent and communication skills. I can survive in this world. I would like the business culture to be a little more friendly, so that my colleagues, who may not be sufficiently communicative but are often more talented than me, would also get enough work.

In my case, the planning of a new comic for a company involves a lot of entrepreneurial reflection. When the desire arose in me to start a family, I consciously began to read business literature. Such knowledge comes in handy in my work with trade unions or, for example, in presenting alternative political options.

The theme of this edition of Stripburger is the radio. You work on the radio yourself, in Radio Študent’s Friday show called Risanka [cartoon, translator’s note], where you draw live following the instructions of callers. In this show you can once again be much more crazy; it represents a kind of return to your earlier period. What does drawing ‘on air’ mean to you?

In fact, I perceive this show as a vent. Even from the time when I was a net recipient of family finances, I have always imagined Fridays as a vent. For the last seven years I spend every Friday finishing off my work for Večer, all this time listening to Radio Študent. I listened to it even when I did not draw as much, and I also occasionally called in on a RŠ show – a show, which was called Lajdra [tart, translator’s note]. When Lajdra was abolished, it was a small shock to me. I called on RŠ and suggested that we start Risanka. Together with Rok Kušlan [presenter of the Risanka show, author’s note) we decided to use technology that I used for Ljudmila; visitors to Risanka’s website are able to follow my every stroke live during the show.

Do you see a connection between the radio and the comics? At first glance, there is no apparent connection. Then you realise, however, that both the media are somewhat reclusive. A lot of cartoonists are connected to the radio (e.g. Harvey Pekar, Jessica Abel) …

Even the early Disney comics were published under the parent company Radio Pictures. At that time, the radio had money. You could say that Risanka is a kind of successor of this story [laughs]. ›››

According to the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, both mediums classify as so-called ‘cool media’ due to their low resolution. A whole lot of information is hidden. With radio speakers you don’t know what they look like and you draw them in your imagination; just like in comics, the reader fills in all the gaps all that occur if you draw a circle with two dots and a bracket. There is little precise information, a lot of complementing.

You are some kind of local patriot. A true ‘Korošec’ (inhabitant of the Koroška region). All my classmates from the Štajerska and Koroška regions know about you and love your work for Večer, even if they do not otherwise read comics. You defend the working man in a true ‘paternal’ fashion, there is no conceit in you. How much does ‘folkiness’ mean to you, accessibility and attachment to the environment from which you originate?

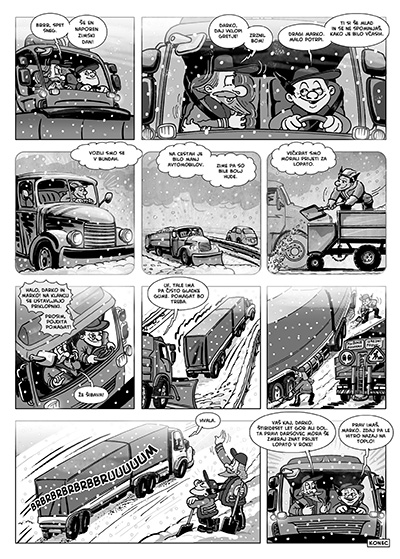

My mum is the one who is cultured – she used to be a librarian, as is my wife. My grandmother was also a ‘madame’. Grandpa, on the other hand, was not cultured; he was vulgar, a maintenance worker in the ironworks, he had no qualms about a fist-fight if there was a ‘jam’. This duality, both elements, are part of me. When I’m making comics for DARS (Slovenian Motorway Company), I love to just go on the road. Observe these warriors of the road, toiling in the heat. When you walk away from your office and go on the road, you hear truly amazing stories. Putting their necks on the line, while at night cars drive past them at outrageous speeds. When you hear such stories you can’t help feeling grateful that someone else is doing this work for you and you simply cannot afford to be arrogant. For me, a great aspect of this project was also in the fact that I brought people from the DARS offices on the road and vice versa. Both were able to better appreciate each other’s work. I love it when I can employ comics to perform a bonding function.

I think you are very successful in that.

I don’t know if I am. In life you can only hope to mainly have good failures. You’ve only got good and bad failures to choose from. There’s no such thing as success.

What do you mean by that?

I would consider it a success at this moment if I had a team of at least five people, drawers and scriptwri-ters, with whom to make successful comics, working more with immigrants, the poor, high risk groups, with people with disabilities. If I were able to produce such comics, I would be happier than I am now.

The failure is that I am constantly running out of time, continuously just trying to catch deadlines, I work at night and I work in order to earn money and consequently I don’t spend enough time with my family. According to Freud, the role in which a man is always unsuccessful is the role of parent. It could also be said that the role in which a man is always unsuccessful is the role of the comics artist. You may be unsuccessful in a good or in a bad way. The creators of Superman were also unsuccessful. They did not protect their work properly and ended up in disputes. Nevertheless, they were unsuccessful in a good way.

Your next projects?

First my degree and then completing my debt to Stripburger, Bridges 3. One day it’ll be done. This trilogy needs to be completed. But I think that Erič and Čoh* took an even longer time to finish off their cartoon, so I still have time. Bunch of procrastinators.

*It took M. Erič and Z. Čoh ten years to complete the first Slovenian animated feature film.

A SHORT BIOGRAPHY

Ciril Horjak is born in 1975 in Slovenj Gradec. He attends primary school in Ravne na Koroškem, where he and his twin brother Metod are comic strip missionaries through the means of a photocopied magazine named Packa od črnila (Ink Stain). They publish an impressive five issues. He continues his comics creations at Ljubljana High School for Design and Photography, where he draws the comic Lejla – vladarica svemira I and II (Lejla – Queen of the Universe). While studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, he joins the influential art group Grejpfrut. Generations of secondary school kids learn quotes from their Poljedelski zbornik letnega pridelka ledenih gomoljev na Kamčatki (Agricultural Compendium of Annual Production of Ice Tubers in Kamchatka) by heart.

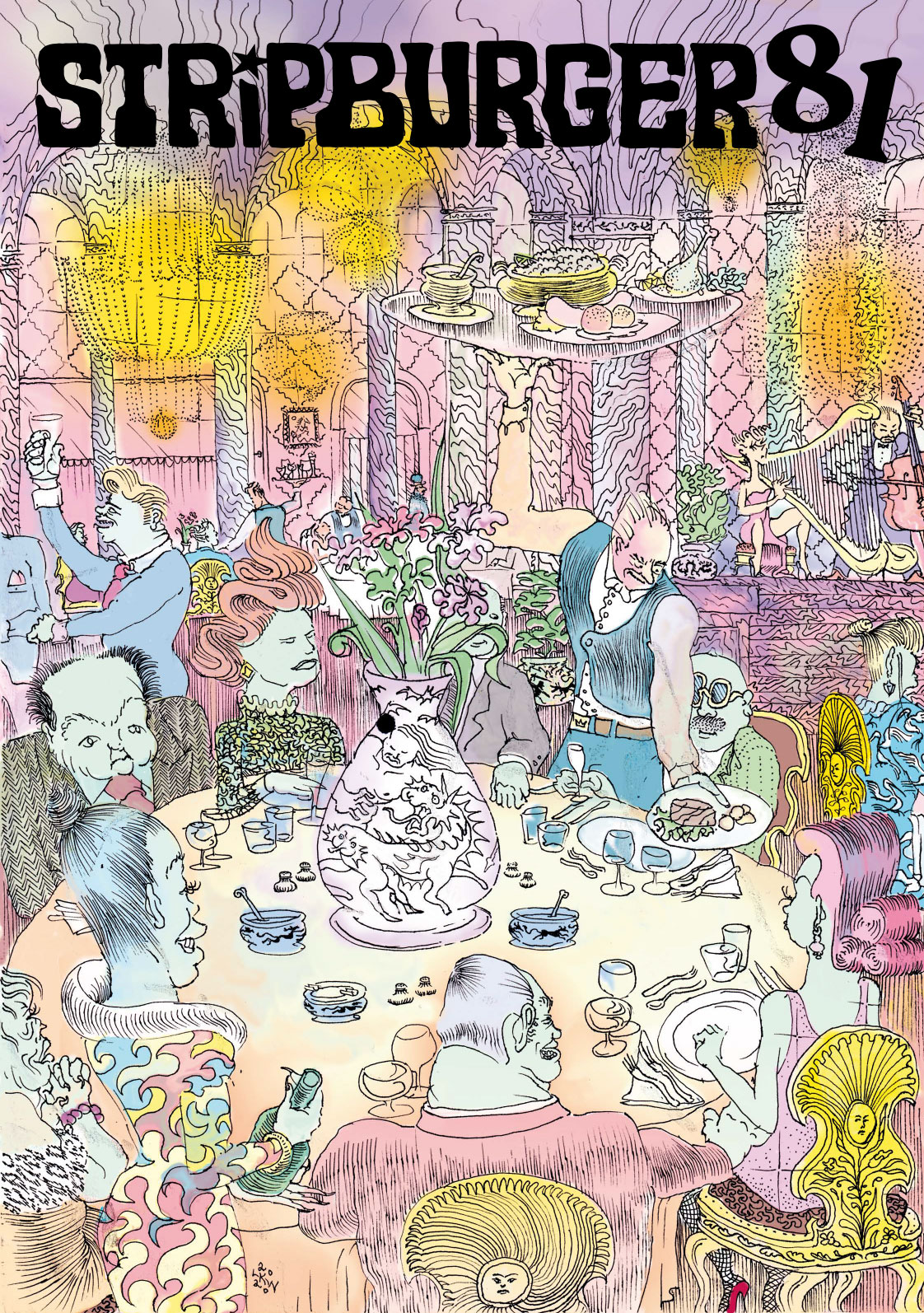

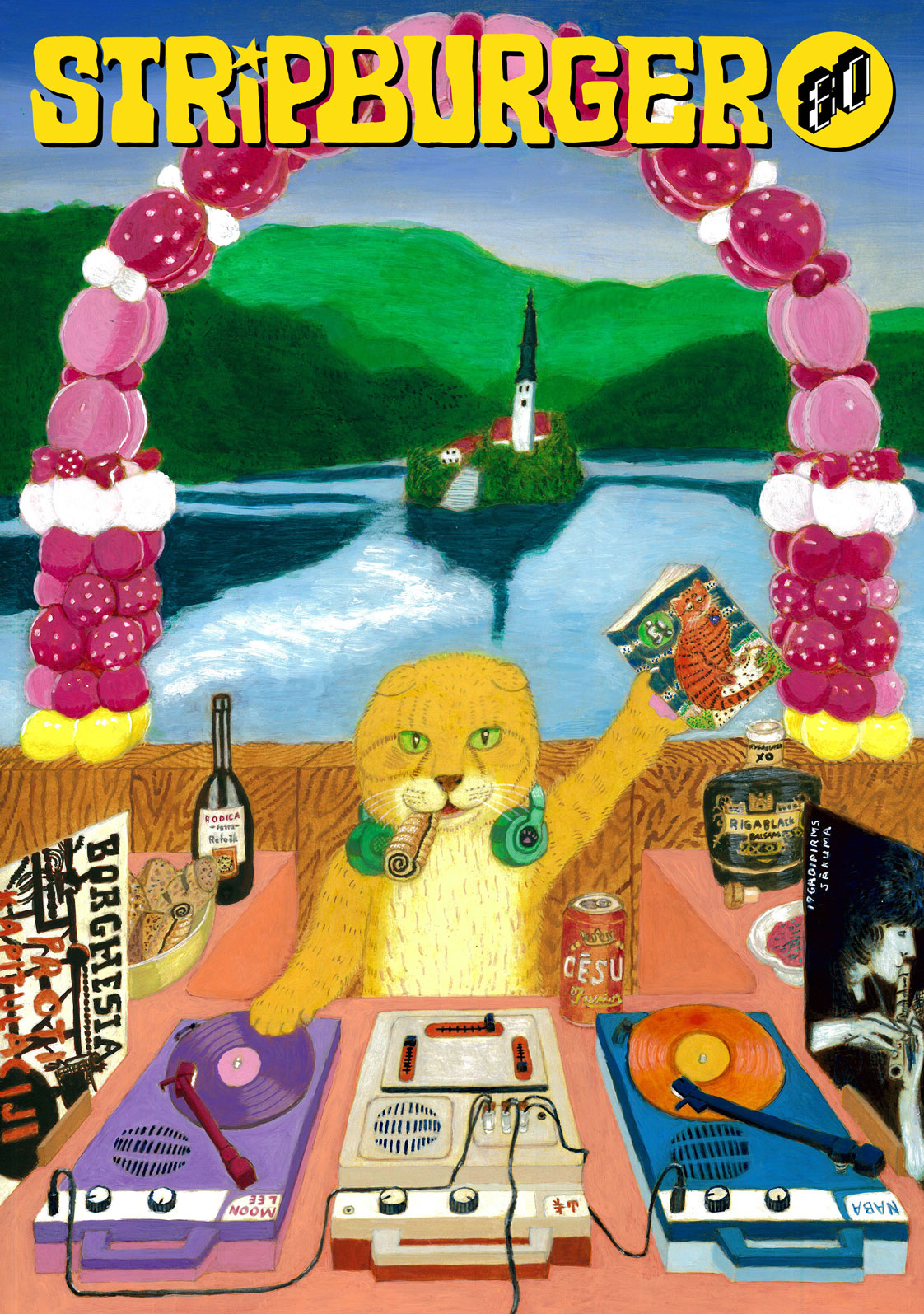

In the nineties he cooperates with the reputable magazine Stripburger, where in addition to his artistic creation he also manages Stripburger’s educational department. Many young talents sprout under his and Matej Kocjan Koco’s mentorship, including Žiga Aljaž, Olmo Omerzu, David Krančan, Milan Plužarev, Domen Finžgar and Martin Ramoveš. He continues his educational mission with Najmanjša velika enciklopedijo stripa (The Smallest Ever Encyclopaedia of Comics) – for kids – and a series of educational comics entitled Kuhna (The Kitchen) – for more grown up audiences.

He expresses his social and political engagement most vividly in 2003 with a series of posters against Slovenia’s accession to NATO, which is one of his few unsuccessful projects.

Outraged by the typeface and technical implementation of Maus 1 in Slovenian, he intervenes and creates a sophisticated font for the reprint of the unfortunate issue. He presents author Art Spiegelman with a graphic from the limited series, for which the artist expresses his heart-felt gratitude.

Despite his numerous projects, he still finds time for friends, to whom he recites his metal and folk songs while sipping coffee or drags them rowing on the Ljubljanica in the middle of winter. In short, Ciril is a family man and a man of the world.