Zoran Smiljanić (Slovenia) – interview, Stripburger 68, November 2016

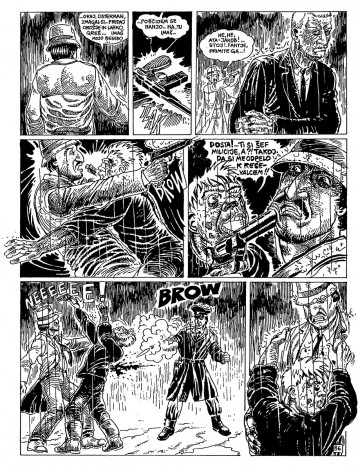

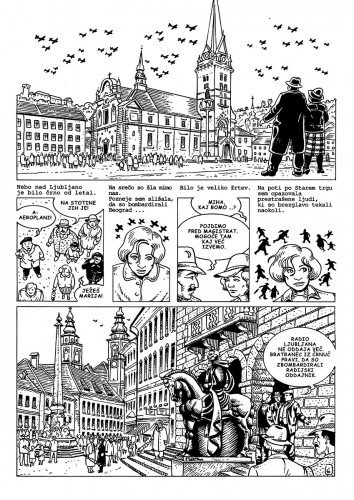

Zoran Smiljanić, a seasoned veteran of comics, a cinephile and a publicist, has a plethora of iconic albums behind him and an even greater amount of new ideas and plans in front of him. A long decade of hard work done by him and the scriptwriter Marijan Pušavec has resulted in the longest Slovenian comic book epic titled Meksikajnarji. He took some time for us despite his exhaustion and told us ‘a few’ things about this feat.

[Bojan Albahari]

Let’s start at the very beginning. Tell us about your first encounter with comics. How do comics artists start off? What’s your story?

No one is born a comics artist, it’s something you become. If you’re exposed to immoral influences early and long enough, you will sooner or later succumb to sin and misdeed.

Comics entered my system at a very early stage, already with my mother’s milk, so to say. In the 60’s, when I was growing up, I was exposed to the damaging influence of several comics publications: apart from Zlatna Serija and Lunov Magnus Strip there were also Panorama, Stripoteka, Plavi vjesnik, Pobjeda, Biblioteka Lale, Super strip biblioteka, Nikad Robom, Politikin Zabavnik, and of course Zvitorepec and so on … All my older peers were reading comics and they forced me to try them. At some stage I gave in: first one, then another and another, until I was hooked. Soon I was swallowing enormous quantities of comics and gorging excessively on them. Parents, school and society tried their best to protect us from this contagious disease that preys upon the young, clean and innocent souls, but it was all in vain. Sometimes they organized raids, confiscated the comics, hid or burnt them, I don’t know, but they weren’t able to uproot them. We’d hide them, exchange them in a highly conspiratorial way, and later they’d be around again, forcing the defenders of the morals to raise their hands in defeat. Comics contained something special, a secret, a magic that we kids instinctively took on, accepted as ours and got addicted to. But my problem was even greater: compared to my peers, I used to experience comics (and movies and books) in a stronger way: they always hit me like bolt of lightning and put me in a trance like state. I was very young when I contracted this addiction of the worst kind; it was so bad that even my peers started making fun of me because of it. I began hiding my obsession from them – I was an outcast among the outcasts. Outcast squared. This is my sad genesis of a future comics artist.

I suppose you started with the Bonelli editions, the ones we all started with. What did Bonelli mean to you at that time and what does it mean to you today?

Eh, Bonelli, the irresistible king of kitsch and pulp. Bonelli’s comics were my informal education, everything that official culture could not give me. Youth heroes that were mandated by the state, such as Martin Krpan, Peter Klepec and Andrejček the Messenger, could not compete with the likes of the great Tex Willer, the cool Tim and funny Dusty, brave Little Ranger or the invincible Comandante Mark. I also fell heavily for the didactically-adventurous Stories from the Wild West, in which they covered the entire 19th century through the lives of three generations of the MacDonald family. Of course, ‘His Majesty’ Zagor was on top of the pyramid. Zagor had something that simply made kids’ fantasies come true. Kids’? Heh, I know quite a few grown-ups who still swear by Zagor, idolize him, buy his comics and stack them in perfectly aligned fetishist collections.

The Bonelli fairytale lasted as long as my childhood, but with puberty, the first cracks appeared. I was 12 or 13 when I noticed that the stories all had the same template, that they were repetitive, that the creators lacked inspiration or that they were trying to cover this up with fantasy that did not truly belong in the Wild West. The heroes were becoming increasingly infantile, the villains moronic, the situations forced, the dialogues stupid, the humour unfunny, the action lazy and not thought-out. I remember the increasing feeling of dissatisfaction and aversion for Bonelli comics. The first to fly through the window was Il Grande Blek who was borderline retarded. He was followed by Comandante Mark and the rest of the bunch, the penultimate was Tex, and in the end even Zagor got dethroned. I was angry with them, I felt they let me down, that they took me for a fool and that they weren’t even close to what they used to be. Back then I didn’t realize that I was the one who changed, not them. They stayed the same and they still remain the same. Well, the only exception and the only one I am still happy to read is Ken Parker, who improved with each episode and is the only Bonelli character to have met his demise. Glory to him!

Then came Metal Hurlant and Alter Linus magazines. These convinced you that comics can be different, that they could address grown-ups, and that you can draw. How do you see this scene from the 80’s now? Do you still find them relevant and inspirational from today’s perspective? How do you see them as a reader and a comics artist?

It actually started in the 70’s, for the first Metal Hurlant was published in 1975. I got my hands on my first issue of the magazine two years later, in 1977, when I was 16. My older brother brought me issue No. 16 from Paris. There were huge red letters on the cover saying DANGER! NUMERO RADIOACTIF, so it must’ve been a radioactive issue. Wow! When I flicked through this wonder, I felt my body temperature rise and I became dizzy. It changed my life. These comics were something completely different from what I used to read before, it was like they came from another planet. Those were comics that addressed intelligent grown-ups, not frustrated kids. Metal Hurlant provided me with everything the other magazines avoided: juicy violence, perverse sexuality, black humour, political engagement and aggressive anarchism. The drawing and storytelling style were new, different, elaborate and artistic. Metal Hurlant catapulted the comics genre into unimagined heights and after this no one could call comics ‘pulp fiction’ anymore. I read that issue at least a thousand times, studied every minor detail, even the ads, learned French, tried to figure out the jokes I couldn’t understand, and absorbed all the different styles and artists. The comics story that made the strongest impression on me was Absoluten Calfeutrail from a certain Moebius. Only later did I discover that this was the pseudonym of Jean Giraud, the creator of my favourite western Blueberry. Moebius was a comics wizard, an artist with limitless imagination, virtuosic drawing and stunning innovations all of which influenced me greatly.

I soon realized that I wasn’t his only fan, but that he was admired and copied by practically all young comics artists in Yugoslavia. We all imitated him, we all did the same hatching, we drew similar wacky and bloody stories, imitated his lettering and used the same letter E like he did (three horizontal lines without the vertical one). Zoran Janjetov from Novi Sad perfected the emulation of Moebius’ style and soon realized the dreams of any up-and-coming young artist: he became Moebius’ successor, and started drawing for prestigious French publishers and collaborated with the great Alejandro Jodorowski. He’s a master drawer, a creative and witty artist, but he got completely lost in his role model. He became his copy, a replica, reflection. The true Janjetov remained undeveloped and non-realized, like a premature foetus. And this is the problem. Regardless of how revolutionary the role of Metal Hurlant and Moebius was, a fan has to detach himself from his role model and find his own way. You need to kill your gods, no matter how big and important they are. Even if our insignificant fates lie in such a desolate place as Kranj.

How do you see Metal Hurlant and ‘holy’ Moebius today?

When I flick through the old issues of MH, they seem worn out. Some artists have aged well, others not so much, but their time has definitely passed. They were radical and striking, they were alternative and avantgarde, but that was years ago, today they’re mere dusty classics. Are they still relevant and inspiring? I doubt it. Well, not for me anyway. You should ask the younger generation of comics artists.

Even Moebius isn’t what he used to be. When he died in 2013, I wrote a respectful eulogy in which I stressed the important role he had for comics and even movies. But I left out the fact that with the Nez Cassé (Broken nose, 1980) album his Blueberry series became somewhat watered down, empty and unsatisfactory compared to the high standards he’d set in albums from Chihuahua Pearl (1973) to Angel Face (1975). His virtuosic drawing could not compensate for the certain apathy and laziness that could be found in the scripts, his solutions became routine, there were no more turning points in the story. I’m not saying it was bad, but there wasn’t a spark, there was neither excitement nor passion, the hero did not evolve, but only rested on his laurels. That was Giraud, what about Moebius? Igor Kordej surprised me once, when we were out having a beer, by saying that “Moebius was an artist who drew wonderful comics about nothing”. From that point onwards I saw my idol in a slightly different way. He really was an extraordinary poet of the subconscious and an explorer of surreal landscapes, but what was all that in aid of? This was something that was already done by the avantgarde movements at the start of the 20th century. Did he say something new about the world we’re living in? Did he offer an analysis of our times? No, he focused on sci-fi, on the comics medium and most of all, on himself. Can his comics be seen today as pretentious ego-tripping, as a superb form without content or as pseudo-intellectualistic masturbation? Surely we can. He was great, maybe the greatest, but time wasn’t very kind to him.

Many remain nostalgically faithful to the comics of their youth even 20 or 30 years later. By this I mean both ‘zagorists’ and ‘moebiusists’ who represent the majority of the clientele at Sandi Buh’s comics shop. Is it just about nostalgia and clinging onto proven comics material? Which contemporary comics (artists) can perform the same role today as Bilal and Corben did for you?

He he, that’s an interesting diagnosis of our comics reading scene. I’d add ‘alanfordists’ to your two groups, for they represent a rather numerous and extremely resilient segment of our comics readership. People tend to grow fond of a certain period in their lives and they get stuck in it. It’s where it was nice, warm and cosy, which is why it’s hard to leave this nest. There is nothing wrong with this in principle, it only becomes a problem when ‘zagorists’ belittle those faithful to Moebius and these look down on them back, while the ‘alanfordists’ despise everyone. I think these polemics are unproductive; it’s like arguing whose religion is better, more true and meaningful. They’re all nonsense. It’s a dogmatic dialogue between the deaf and the blind who have dug into their trenches and won’t budge. As a man who has admired both Zagor and Moebius, and then left them both behind, I know it’s not about the comics, but about those who read them. Your view is not defined by Zagor or Moebius, but only by yourself. When I speak about those clueless and tasteless ‘others’, I’m in fact speaking about myself.

But I don’t want to be overly sharp: Buh’s comics shop attracts interesting and wacky characters who even argue in an amusing way. I feel at home with these different ‘patients’ with various diagnoses and medical conditions, and I’ve also learned a lot from them. They know a lot about comics, they are the keepers of the most bizarre information and details, they often recommend good reading and in most cases I am happy with their suggestions. Yes, I can still be touched by comics, there are so many good comics, too many, it’s impossible to follow them all. Recently I’ve painfully enjoyed Tardi’s First World War albums, I was swept away by Gibrat’s Matteo and Le Sursis, shaken by Sacco’s Goražde and fascinated by Juillard’s The Seven Lives of Gavilan (and a little less with its sequel). Fibra’s publications are, almost without exception, at least attention-worthy, if not truly exceptional. The last one I’ve read holding my breath was Macan/Kordej’s serial We, The Dead, and their unfinished Texas Kid was also a masterpiece. And of course our own Tomo Lavrič who’s much better when he draws for his own scripts than he is when he draws for the elite French scriptwriters. I closely follow, weekly, his Young Yeshua’s Gang and it’s ‘bloody excellent’.

Let’s remain with Buh’s comics shop for a bit longer. Today it seems like he’s always been there, but he hasn’t. How did you manage in the times before Buh, before the internet, the computers and digitalization?

Yes, Buh’s den, in which one can hardly turn around, is much more that the sum of the square meters he occupies. He’s got a few competitors lately, but he’s still the main dog, the epicentre of Slovenian comics. But there was also the time before Buh.

When I began publishing in Mladina in 1987, I was more or less left to my own devices, just like all the other artists. The comics were analyzed and directed by the editor Ivo Štandeker. At that time, evaluation between artists was rare: you got a friend’s opinion every now and then, and that was it. In Mladina’s golden era, when their print runs exceeded 80 thousand copies and I was present in God knows how many Slovenian homes, I lived in a perfect vacuum. I didn’t have a clue whether anyone was reading my Hardfuckers comics story, I didn’t know whether they hated it, ignored it or got it, whether what I was doing made any sense to anyone. There was no reflection, no feedback, no readers letters, nothing. I spent long years in total darkness and this situation started to appear normal to me. Then Buh came along. I started visiting his comics shop and I met some new kids there who took comics very seriously and also knew a lot about them. Finally! I was literally moved when I saw them meticulously cutting out the pages with my comics from Mladina magazine and binding them into some kind of funny brochures. This is how I entered Sandi Buh’s orbit. He has become my second mother.

Buh is no comics theoretician, but he’s also no ordinary peddler. He loves comics, he’s a great connoisseur and a collector. He has established a scene and connected people for whom comics are more than merely entertainment, even though we do get on his nerves sometimes. He’s an organizer, promoter and manager, which is something we artists direly need, as the majority of us aren’t able to take care of ourselves. He sets up presentations and exhibitions as well as places comics in the media, he attends all kinds of comics events, he thinks and acts in the long run. The reputation of Slovenian comics has risen, his comics shop hosts presentations of domestic and foreign artists, he even brought my hero Hermann Huppen to Ljubljana. And when he started publishing a selection of the best domestic artists, he became a true spiritus movens of the Slovenian scene, a padre padrone, godfather Buh. If I would try to illustrate his real importance (and weight, hehe) I would have to imagine there is no Buh, that he never existed at all. Can you imagine a world without Sandi Buh? I, for one, cannot.

You acknowledge that both comics and movies have shaped you significantly, especially genre movies, specifically western. This must be the reason why numerous people consider you the most movie-like among comics artists in Slovenia. Do you also believe that you’ve shaped your comics language to resemble the movie language or that movies influenced your drawing (montage, framing)? What do you think about these ‘malevolent insinuations’?

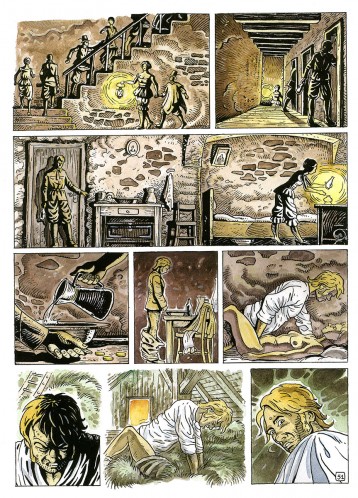

I admit that this has happened, but I don’t feel guilty. I just obey the orders from my superiors. I’m but a cog in a well-greased machine, a tool in the hands of generals that define and manage my activities. The order how to draw something comes from my centre for visual projection in my brain, where the headquarters of the visualization of specific scenes is situated. I don’t argue about why it should be done in one way and not the other, I merely follow the instructions down to the letter. If they tell me I should draw long horizontal scenes that resemble the cinemascope view, I do that. Usually they want me to include a part of the previous picture in the following one, so that the comics story has continuity and movement, and I comply. The bosses don’t like it when the frames are scattered all around, they expect a certain order, arrangement, inner structure and logic, and I stick to this blindly. I’ve also noticed that they prefer certain movie compositions, panel layouts or the rule that the size of the image should be equivalent to the length of the movie scene (i.e. the smaller the image, the shorter the scene) and I attentively execute this. If they want me to kill innocent people and have blood splattered all around, I will do that without objections. I’ve ‘taken care’ of hundreds of characters, but my conscience is clear and I sleep peacefully at night. The work usually runs smoothly and without delays, but sometimes the communication between the headquarters and my hand breaks down from unknown reasons. No orders are given by the centre of operations, there is only silence, thumping in my temples. Then I have to find a solution for a specific scene by myself and that’s the hardest part. That’s when I can feel the burden of free will and independent thinking. I stare at the blank sheet of paper for hours and I have no idea what to do. Those scenes are not just born in torment and pain, I de facto miscarriage them. Then communication is resumed, the superiors scold me for my poor performance and send me new instructions. This is why I don’t feel responsible for my work and I deny feeling guilty for all charges.

Who is Vittorio de la Croce, and what’s his role in all of this this?

De la Croce is a dissembler, a hypocrite and a coward. He’s a made-up persona I’ve hid behind who made it easier for me to continue with my work. In the 80s, when I first started publishing comics and provoking the authorities, the government, the tradition, the nation and the municipality, I quickly felt the consequences. I was locked to a pillory in my job at that time, and one of the secretaries with whom I got along quite well gave me a reproaching look and said, in a disappointed voice that she didn’t expect something like that from me. Criticisms from my comrades came in abundance, the municipal authorities were all rabid and demanded responsibility. But I shat in my pants when I was told by a reliable source that people in the YLA (Yugoslav People’s Army) headquarters have discussed my poster Tedna mladih Kranja ne bo! as proof of a ‘counter-revolution’. And you couldn’t joke with the army, they could come for you and the night would swallow you. When I began publishing Hardfuckers in Mladina, I picked a pen name to protect myself, and all other Mladina’s artists soon followed suit. Thanks to this we could draw nasty stuff and make fun of the regime. When Lady Liberty, justice and democracy came to our beloved little country, there was no more need for Vittorio, so I discontinued him. With time, I’ve become increasingly patriotic, submissive and obedient as an artist, finally selling myself out to the system. Maybe I need a new pen name now.

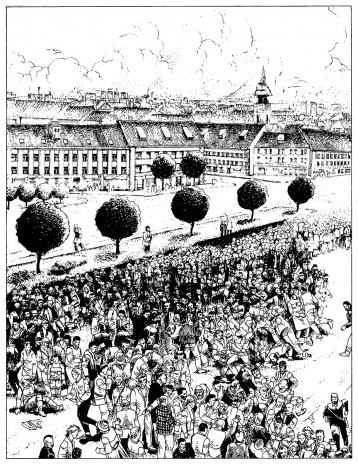

You and Pušavec created the longest comics epic in Slovenia. Any domestic comics reader knows Meksikajnarji. How do you feel now, having completed this saga that took you almost a decade? You seem quite worn out.

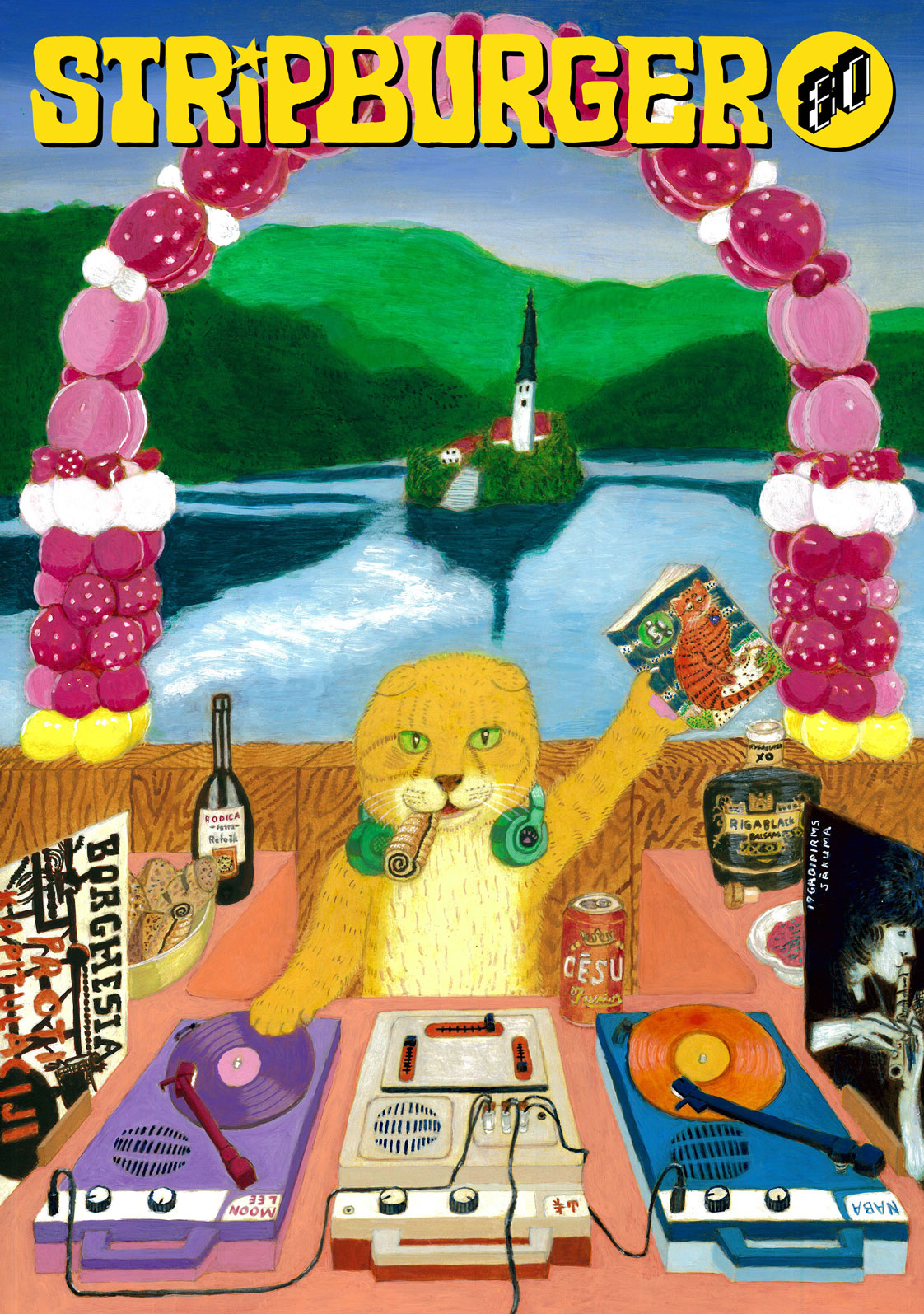

Yes, it was exhausting. I’m completely burnt out and empty, which is why I’m not able to draw the obligatory comics story for this issue of Stripburger. When I mentioned this to your ‘high priestess’, she said she’d tell me to fuck off. Luckily the new generation of editors is more sympathetic and lenient. Shoot me, I just can’t do it.

Many people doubted I’d be able to complete the story and maintain the quality level I have set in the beginning. Even I had similar concerns. I’m a guy who likes to do different things, I like to switch from comics to illustrations, from writing to drawing caricatures, from graphic design to scriptwriting. I find working on a single project for long periods at a time tiresome. Osterman, one of my characters in Hardfuckers, sums up my feelings at the end of the book when he says: “I’m tired … I’m so tired.” The Meksikajnarji story is significantly longer and in full colour, which is why it was so tiresome to draw it, it was difficult to maintain the concentration, motivation, dedication and energy, especially during the second part of the last tome, when I’d rather be doing anything else, even cleaning the house. If it wasn’t for Mladina that compelled me to work by weekly publishing the pages and thus depleting my comics reserves, it’d take me much longer to finish it. Then, I finally wrote THE END OF PART FIVE, drew three more pages of the epilogue and said to myself: “You’ve finished it. Dammit, you did it.” With the fifth tome I’ve crossed a kind of a personal border, an invisible barrier, and arrived where I’ve never been before. Now I have a better understanding of those madmen who drag themselves to the North Pole or swim the Amazon. This is not an epochal achievement, for numerous professionals create the same number of pages in two or three years. Compared to the intimidating opus of, let’s say, Marcel Štefančič jr. or Igor Kordej, I’m still an amateur and a lazybones. I don’t feel special triumph or pride over this, I’m merely glad it’s over and that I can rest. Elementary things.

You divided the work with Pušavec, as a work this long would be too demanding for a single author. Does such a collaboration work out in the end?

Of course it does, a single author would never have come this far. If two people create together, they contribute two life experiences to the project, two viewpoints, two approaches, and the project is much richer because of that. I grew up comfortably on genre movies and comics, i.e. in pure fiction, while Marijan Pušavec was forced to do craftwork and farm work at a very young age. I’m a city dweller, while Marijan is a farmboy. I’m a failed student, Marijan is a graduate of comparative literature. I contributed laziness, non-demandingness and hedonism, while Marijan contributed knowledge, diligence and experience to the project, so I could say our shares are equal. We’ve been good friends for a long time, we share a similar worldview, the only question was whether we’d collaborate well together. You know, friendship and business do not mix well together. Well, we passed the test period with flying colours: he helped me solve a problem with Hardfuckers when I encountered a dead end, and in the second part, where he was involved from start to finish, we has a successful collaboration, since this part is considered the best part of the trilogy. Meksikajnarji was an incomparably larger and more demanding project, thus we stepped into in thoroughly prepared and reached an agreement what kind of comics story we wanted to create. The creative process was described in detail in the previous issue of Stripburger, thus I won’t repeat it, but I’d still like to note an interesting thing I’ve noticed only at the end of the project. Once we created the outline of the story, I drew a storyboard which was to serve us as our basic plan, but then I created the scenes my way, without consulting Marijan too much. I assumed he was not interested in this, that the visual solutions were down to me. However, from time to time he would express mild discontent: “I didn’t imagine this scene the way you drew it.” Then I read the interview with the script-writer Alejandro Jodorowski who admitted that he was sometimes appalled at what the artists have done to his story: “I imagined one thing and they’ve drawn something completely different. They got it all wrong, they fucked up, they ruined my script.” But he didn’t say anything. With time he realized that every person has his own vision, his way of doing things, that there’s no right or wrong vision. He has accepted the fact that everybody sees and solves things in their own way, no one can be forced to do it your way. I’m not saying this just so Marijan would give me a break, but I did realize at a rather late stage that the writer, a man of words, has his own vision and should have greater influence in the creation of the visual part of the story. We’ll do this next time, amigo.

Did you stick to your original plan or did you change some important things as you went along? How do you see your collaboration now? What did you learn during this time?

Basically every writer/artist duo chooses their own type of collaboration. Some like it when everyone does their own part without tampering with the work of the other, while others work together in every aspect of the creative process. For instance, Charlier and Giraud never met during their years of collaboration: Charlier wrote the script and sent it to Giraud, Giraud drew it in his way and the writer saw the result only when the comics story was finished. There are no rules. With Marijan and me, we were both in constant reciprocal control of each other. I could’ve strayed in my enthusiasm on several occasions and ended up god knows where if it wasn’t for Marijan who coldly and rationally led me back to the right path. It is priceless to be able to think with a cool head about something that seems like a great idea to someone else, as it usually turns out that the great idea was complete bullshit.

We’ve mostly stuck to our plan, only once did we have to deviate from the planned route: we were tempted to prematurely end the career of our main character, but after a long and thorough discussion we decided not to sacrifice our main story arch merely for the sake of an original and wildly effective momentary effect. Thus we returned to the original plan and we kept that idea for another story. However, we did implement one major change: Tone was originally supposed to be present at Max’ execution, which would be their third and last meeting. But then my wife suggested a great idea for the finale and we scrapped the intended ending without hesitation, although this came at the cost of this nice symmetry. We’re not sorry, for the final result is incomparably better.

In short, creating Meksikajnarji wasn’t a duel of two egos, which often happens in tandems, instead we’ve just dragged our rickety wagon somehow in the same direction all the way till the end. And we did it and I fulfilled the initial promise.

When I look back, I think it was of vital importance to have this initial wish, this passion and need to tell this particular story. It’s abstract and intangible, it can’t be merely created, I don’t know where it’s coming from and what’s its purpose, but it’s essential to the whole process. There would be nothing without it. If we both have this, and we did, it’s a good start, although it is not a guarantee for success. First there’s this spark, only then come money, fame, the capability of supporting the family, recognition and other motivations for work. I also haven’t learned anything, I’ll be merrily doing new mistakes in the very next project.

I’m asking because our comics scene, which is historically characterized by comics in which the writer and the artist can be found in the same person, is currently experiencing a shift into increasingly more common collaborations between a writer and an artist, most often in the field of children and youth comics. Unfortunately, the editorial casting and pairing of artists often doesn’t work very well. What needs to be taken into consideration? What are the advantages and pitfalls of this kind of production process? What kind of advice would you give to the editors?

The relation between a writer and an artist is like a part-time marriage. A thousand details decide whether it will work or not. You may fit wonderfully, work great together and create a crappy comics story. You can torment, torture and hate each other, and then produce a wonderful piece of work. There is no recipe, you won’t know until you try. Since it’s a very intimate thing, I suggest that they are sent to a motel for a week where they can communicate at will and try everything, from the front, from the back, on top, on the bottom, domination, S&M, chandeliers, badger, rabbit, impressionism, futurism and neo-folk … If they fit together, great, make them create comics, if not, try someone else.

Now that Meksikajnarji is finished, how do you see you work as a whole? Have you succeeded in realizing your vision? Would you do something different?

I’m pleased with the story and the way it was told, and I am also pleased with the atmosphere. I am not pleased with the drawing and I think the colours are so-so. I just can’t seem to draw like I’d like to, there are still plenty of mistakes and weak spots. Fuck it, this is my reality. Except from this, the first part, Miramar, is very ‘stiff’, it should be drawn anew, but who’s going to work on this for six more months? When I flick through the earlier books within this story, I’m amazed about all the meanings we have managed to capture and all the layers that can be found in the story. I like the fact that it contains more humanity and optimism than my earlier works which were all more tragic, fatalist and pessimistic.

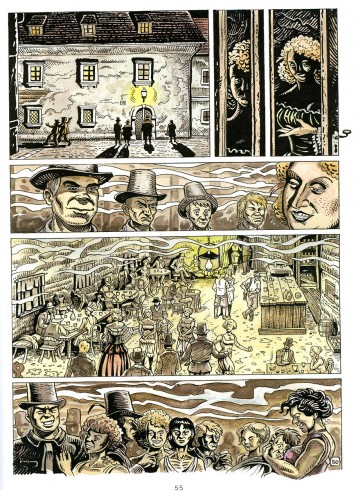

At this moment I am most pleased with the final scene of execution/birth that came out better than I expected. The two parallel co-existing stories of Max and Tone are condensed and closely intertwined at this point. The rest of the story is composed of scenes running though one or several pages, alternating between Max and Tone, but here the story is condensed and we have alternating frames instead of pages, which gives the action the appropriate dramatic quality as well as a strong emotional charge. This condensation of events works great as a formal climax of a two-tiered storytelling, especially since this alternation of frames brought with it a new quality, new meanings and effects I didn’t plan and just happened by themselves. I haven’t enjoyed drawing like this for a long time and I wondered what was going on. It was some kind of a drawing orgasm that happened to me maybe three or four times in my life. A door opened and let me into this new dimension where it’s … nice. It was an unexpected and sweet reward for my previous work.

You previous comics were colourful, but drawn in black & white, while Meksikajnarji is your first comics story in colour. How did you decide for this and why? What did this mean for the drawing and the creative process? Was it an attempt to appease today’s spoiled readers who demand colours, or was it an autonomous artistic decision without any ambitions to please?

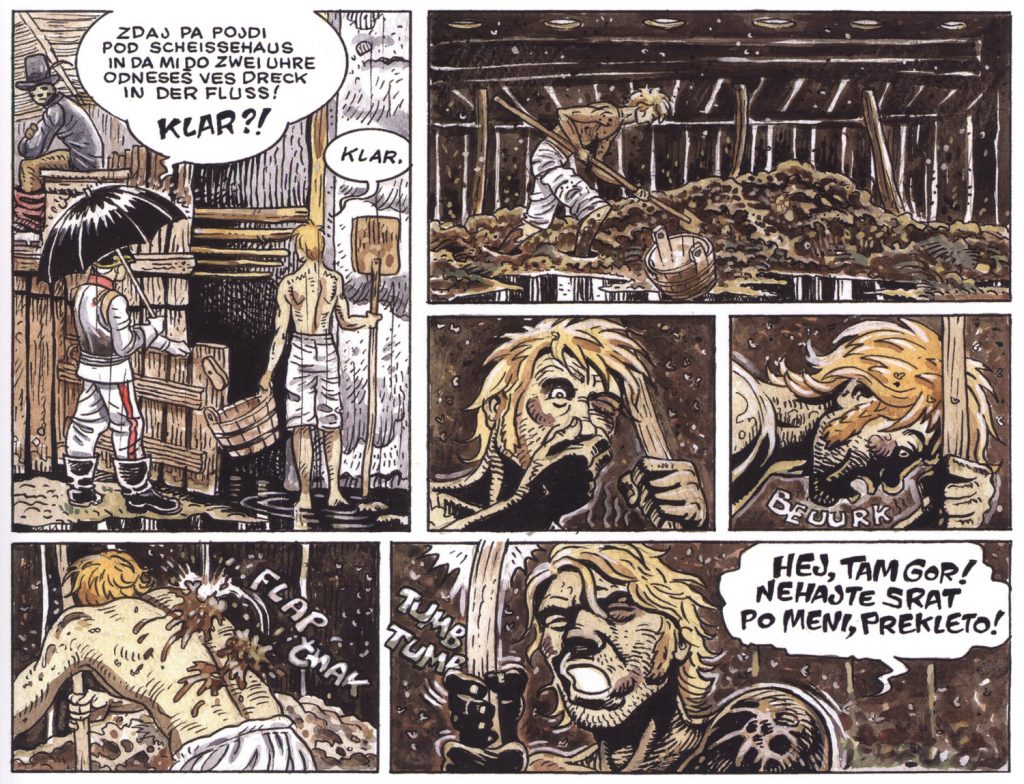

The choice for colours came from Robert Botteri, the editor at Mladina, where Meksikajnarji was periodically published, who nonchalantly informed me that their magazine was in colour and that he wanted comics in colour. I agreed to this without thinking about it twice as I thought Meksikajnarji needed colours and I wanted to try something new. Okay, alright, no problem, I said. And this complicated my life greatly. I’ve created some single page comics in colour earlier for the PC & Mediji magazine, but they were colorized with the computer, while this time I didn’t want to use the computer as I felt it didn’t fit the 19th century theme. So I have done it all by hand, using watercolours, temperas and markers. There was lots of experimenting, lots of applying colours and lots of cursing the idiot who convinced me to do this. Well, now that I’ve finished it, the unwanted bastard turned into a little prince. Now I’m the proud father of approximately 350 original pages that I can touch with my hands and not just browse in some digital labyrinth. Meksikajnarji is one of the rare products of the dying-out domestic handicraft.

You used to be more daring and provocative (the poster for Teden mladih Kranja, covers for Mladina), what about today? Have you abandoned this or have you merely cunningly hid it between the lines/frames/bubbles? What does a modern comics artist have to draw to be edgy and provocative?

One calms down with years, it’s inappropriate for a middle-aged gentleman like myself to stir things up. I have also thoroughly vented all my rage and anger from my younger years, there is simply no need for that anymore. Now I’m pushed to the brink of tears even with a nice landscape painting or a bouquet of flowers. Furthermore, Meksikajnarji is such a sure-shot work that I cannot possibly offend anyone. I’ve even heard those ‘patriotic’ Hervardi like it and promote it on their webpage. I guess they didn’t pay attention to the artist’s name…

It is hard to be provocative in the times of the internet which is full of brutal accident videos, shocking pornography, sadistic executions and pathologies of all sorts. I wouldn’t even want to compete with that. Circumstances have changed and we need to find new forms of expression. It’s not easy, the times of activism and provocation are over. What can you do? If you’re provocative and focus on a particular individual, he’ll sue your ass, if you’re provocative and focus on politics, a few strong guys will wait for you in the dark, if you rant against capitalism, it’ll buy you off and profit from your work (in the best case scenario). The most likely option seems to be a print-run of a few hundred copies and a life in mid-misery.

Lately I have noticed a growing self-confession trend. Artists have turned away from the big themes and are unreservedly revealing their intimacy, washing their dirty linen in public and sharing all of the family secrets.

They’re doing this so sincerely and without any reservations, that it’s almost embarrassing to read it. I’ve noticed this in literature (Pascal Bruckner: Un bon fils, Karl Ove Knausgård: My struggle, Miljenko Jergović: Father and the Slovene Gabriela Babnik: Intimate and Miha Mazzini: Childhood) as well as in comics, for example Nina Bunjevac with her Fatherland and Samira Kentrić with Balkanalije. Recently I have read the shattering Catharsis by Luz, the caricaturist who luckily avoided death during the terrorist attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. The artist faces his life after the tragedy painfully, sincerely and with bitter humour. Luz is very tough on himself, just as Charlie Hebdo was tough on everyone. Same measure for all. I think this new intimacy that goes all the way brought a new viewpoint, a new approach and new subversiveness. By revealing these extremely unpleasant and traumatic secrets that any normal person would bury deep into a dark pit so no one could see them, the artists are not merely talking about themselves and their experience, but also about the wider society and the times we’re living in.

Alongside the genre (western, historical), a socially critical note is constantly present in your works. What do you think is the wider role of (comics) art? Is it enough to entertain and thus offer an option to escape reality? Is this escapism subversive enough, or is there a need for something more?

Well, I don’t have the ambition, ability or wish to deliberate on the socially-artistically-critically-subversive role of comics. I’m just not competent enough. I don’t want to be a promoter or a comics advocate: comics are actually getting on my nerves, since I’ve wasted half my life on them, worried about, suffered failures, terrorized my family and made their life worse with my drama & discontent when something went wrong. I don’t care about comics, they’re merely a medium, let them deal with themselves or die out, if their time has come. If I was able to bullshit about the role of comics art, I’d rather work as a bureaucrat or an official and receive a hefty pay check at the end of each month.

I just happen to like edgy stuff that transgresses the boundaries of genre, I dare to do this and I know how to do it. These are the stories that I’ve enjoyed the most as a reader and I also enjoy doing them as an artist. I deal with topics that I find important, that relate to me and which I can say something about. I’m not really interested in the rest.

Your first, early comics were surprisingly not published in a specialized comics magazine or general periodicals for a wider audience, but in the Music Lovers’ Association bulletin. How did this happen? Couldn’t you get them published anywhere else? Did you know the editors personally? Do you like music in the same way as you like comics and movies?

That was in 1981 when I returned from serving my military duty and I was eager to get published. The true question is whether I was ready for it or not. At the time there was no magazine in Slovenia that would publish comics, especially not ‘alternative’ ones. The Croatian Novi Kvadrat has just established itself in the youth press segment, the comics scene was getting increasingly stronger in Serbia, while in Slovenia there was nowhere I could send my comics to. The only one who seriously dealt with comics at that time was our guru Igor Vidmar. I remember visiting him in the company of other up-and-coming comics artists (joined by Dejan Knez and the late Tomaž Hostnik from the band Laibach) as he intended to create a special comics issue, but the meeting was a failure. He criticized us and sent us home. Thus I turned to the club KLG in Kranj, where youth gathered in a cellar where they listened to music and published their bulletin. It was an A5 fanzine printed with an ancient technique of cardboard clichés. We soon struck a deal and I finally lost my comics virginity. The first comics story Folk Against Rock was related to music, while in the second one I picked a different direction and made fun of Kranj. The third one was about Metod Trobec (infamous Slovenian serial killer) and this helped me gain recognition at the all-Yugoslavian comics contest as well as at the Vidiki contest. The fourth and last one was Balada o dveh vojakih in treh baletkah (A ballad of two soldiers and three ballerinas), a mute exercise in style that followed the visual styles of Alfonse Mucha and Sam Peckinpah. Then it was time to move forward …

Yes, music is important. I have been listening to music since I was a child, at that time Sweet and Slade were all the rage, later came prog-rockers such as Pink Floyd, ELP and King Crimson. As a teenager I was into punk, in the 80’s I listened to Yugoslavian and English new wave, in the 90’s I was a fan of Dead Can Dance and the Cocteau Twins, while my greatest favourite during all of these times was film music, which I especially enjoy listening to while drawing. As the years pass by I’m turning towards authentic folk music such as American folk, bluegrass and of course blues. I agree with my Croatian colleague Štef Bartolić who said that music was of vital importance in our youth, while now it’s more like an acoustic backdrop.

Meksikajnarji became hugely popular thanks to Mladina, where it was published periodically. What is the role of the media in reinforcing the comics reading culture?

Yes, Mladina’s played a key role in this and it published practically the complete Meksikajnarji story, with the exception of the prologue, the first six pages in which Max and Tone were children. These six pages were included in the album, so nothing is lost.

The story was published in 165 issues of the magazine. Can you imagine the quantity if you threw it all on one spot? The fees dwindled slightly since 2005 when the first part was published, but not drastically. I was able to live off the money I received from Mladina and continue with my work. If it wasn’t for them, I doubt I’d be able to bring the project to the end. I’m grateful to them and I hope they also got something in return.

What’s the role of the media in strengthening the comics culture? Hm, paradoxical. In former Yugoslavia all children read comics, even though the media was constantly saying that they were pulp fiction and a ‘bad influence’ on the youth. Following Slovenia’s secession the flow of comics from the south dried out, we didn’t have any of our own (except in the Mladina and Stripburger circles) and the media was more or less silent. Nevertheless, the scene recovered and today there are more active artists than ever, there are plenty of new publications, young artists are multiplying like rabbits and merrily drawing on, while the media is also doing a good job of covering comics. But will this influence the children to buy and read comics? I doubt it. On the other hand there is no more room in newspapers for domestic comic strips, they prefer publishing licensed ones, if at all. The media is contributing to this, but I wouldn’t place too much importance on it. Comics move in mysterious ways …

Meksikajnarji has been a work in progress for an entire decade. How did you bring home the bacon? How can comics artists live off their work in Slovenia?

While I was creating Meksikajnarji, I concentrated on this comics serial and rejected all other commissions. I worked on some decently paid commissions in the periods between individual episodes and that was how I was able to survive. But Max, Tone and the rest of the gang were constantly on my mind and I couldn’t escape them. The pressure yielded a bit only when I was working on the comics.

Comics artists have a shitty time trying to live off their work, it has always been like this and I sincerely doubt this will change. You can’t live off comics alone, you have to think of something else as well. If you create a little thing here and publish something else there, maybe get some royalties from your books, you might be able to afford some spam and cheap bread to go with it. We all try to survive according to our abilities, which usually means that we patch up the budget holes by performing slightly better-paid illustration gigs, but there is also increasingly more work for increasingly less pay. And there are those rare moments when the effort pays off and you strike gold. I have had more luck than brains on two occasions so far: I received more than a decent fee at the beginning of my career for my second book of Hardfuckers (when Mladina’s print run skyrocketed), thanks to Ivo Štandeker, and the second time for Spomini in sanje Kristine B. (Memories and dreams of Kristina B.), thanks to Blaž Vurnik. These two were like winning the jackpot. The rest is mere misery.

Which is why publishing an original album is always like a special holiday. I respect our artists, regardless if I like their comics, as I know how much they give and how little they get back. Domestic comics see the light of day as a result of enthusiasm, stubbornness, madness, obsession and a hefty dose of stupidity, both from artists and publishers. I’m always a bit surprised when I see that comics just won’t give up, that the scene is expanding and evolving in spite of the adverse conditions. In Slovenia comics are like those solitary trees growing on high mountain cliffs that proudly defy the elements and refuse to cease to exist in spite being put to the test by storms and lightning and … sorry, I got carried away there…

In one of your interviews you said that Stripburger was too intellectual for your taste. Have you changed your mind?

Well, you got me now … time to pay my dues. What now? Nothing, I’ll get away with it like politicians usually do: “you’ve taken my statement out of context”. I have only ironically commented on the difference between comics in Mladina and Stripburger. Ten or twenty years ago, Mladina’s comics were considered more communicative, more narrative-inclined, nicely drawn, funny and reader-friendly, while Stripburger’s were less communicative, more hermetic, obscurantist, avantgarde, subcultural and full of grotesque creatures that were cutting each other’s heads or balls. There used to be some kind of informal division between us, you kind of looked down upon us for being commercial, while you considered yourselves artistic and avantagarde, while we reproached you for being incomprehensible, pretentious and unreadable. However, in reality we all dealt with the same thing.

Well, with years these divisions became somewhat blurred: we became more difficult and you became more relaxed. The excellent comic book entitled Pijani zajec, for instance, is very easy on the eyes and I find it stylistically closer to Disney than Stripburger. I salute this, for we all have to move on. I’ve met many of your artists at the presentations on comics evenings that I’ve been organizing for the third year now in Kranj’s city library, and for me they were all a unique discovery. At first I didn’t really like Andrej Štular, my fellow citizen. I felt that his expressive style was merely a pose and that it reflected his inability to create a proper drawing, but after twenty years of work, I respect him as an artist with a vision and a unique style who’s completely autonomous and idiosyncratic, as well as funny. I like some Stripburger’s artists more, some less, but I do read the entire magazine, I try to understand the comics that I don’t like at first and I often discover surprising things. Give Stripburger a chance. I like the reviews, the interviews and the fact that you’ve been present on our scene for all this time and co-created it. Which is why I hope you don’t mind me and my bombastic statements. Peace?

And peace to you, brother …

So, what is your opinion of the contemporary Slovenian comics scene? Does it lack anything, how does it stand out from the others in a positive sense and what do you find inspiring in it?

It’s a real miracle that it exists in the first place. It lacks many things, but with the huge number of young artists, it sure does not lack enthusiasm and ideas. Generally our scene is very engaged, artistic and peculiar, which I think is a result of the economic circumstances, our extremely small market and the fact that we cannot export comics because of our language. Bigger countries have ‘programme’ comics, e.g. educational youth comics, comical comics, sci-fi, historical, musical, western … comics and all of them are commercially oriented, while there’s only a few artist’s comics. Many great artists from Croatia and Serbia who work for foreign publishers don’t create their own stuff, but work on commercial comics that need be proven on the market. In Slovenia you cannot sell a comic book in a print run worth mentioning, so we mainly create personal artist’s comics, which means that we can proudly state that we’re the land of artist’s comics. Isn’t that nice?

You’re also, to a certain degree, responsible for the state of the Slovenian comics scene, not merely because of your comics, but also because you organise comics discussions in Kranj’s city library. Where does the motivation for a comics artist to do these extra activities and become a comics promoter come from?

It wasn’t my choice; I never had this special need to play the role of a TV-show host. I was led into this by people who know me better than I know myself. They told me I’d be good at it and when the time arose they told me to go for it. So I did. I’m not sorry. I have learned a lot and I have broadened my horizons by presenting different artists and their work, for I was even forced to adopt an active stance towards their work. Even if I didn’t especially like a certain artist, I was able to find something good and worthy in all of them, and I tried to convey this to the audience. Or at least I formed a reasonable criticism. During all this I’ve realized how often I used to be the victim of my own ignorance, blanket conclusions, biases and upfront discreditation. So I did something good for me, for the artists and for the readership. Instead of having a resentful, begrudging and quarrelsome comics scene, I contribute my share to improved relations, a better understanding, communication and respect among my guild colleagues. It may sound pathetic, but I’m really sick of this Slovenian habit of everyone being in conflict with everyone else and of always blaming the ‘other’ side. Izar Lunaček is doing something along the same positive line, only on a larger scale, for I’m merely a provincial weasel who plays the cards he has been dealt. The comics discussions have taken on, they’re in their third year and are showing no signs of exhaustion. This must mean that those who led me into this had assessed the situation correctly and have guided me well. Sometimes it’s good to listen to ‘the men behind’.

What can we expect from you in the future? What are you plans and ideas?

I have loads of plans and ideas, however, I’m a little short on life: the First World War (the Soča front and the Serbian front), Slovenian brigands, short stories about my family, short stories about Yugoslavia, Mrlak, Cankar, a ‘true’ western and whatnot … And that’s without considering the stuff that jumps the line. With God’s help I’ll live to a 150 and draw everything I’ve planned. Even a comics story for Stripburger. To appease the terrible wrath of the ‘high priestess’.