Izar Lunaček (Slovenia) – interview, Stripburger 71, May 2018

Izar Lunaček has been rocking the boat of Slovenian comics for quite a while now, for he’d begun regularly producing comics as a professional author relatively early. One could even say he’s one of the most recognizable and popular comics artists in our country: his comic strips have been published in several different newspapers and magazines, while almost all Slovene comics book publishers published at least one of his comics books. Even though he has been interviewed several times in the past, the interviews were never like the one we did for this issue of our magazine. Get ready for a less than decent exposure and enjoy the striptease. (Krančan and Albahari)

If we look at the sheer amount of your works it is perhaps best to start with the Minis which was your first regular comic. Conveniently enough, you’re celebrating the 20th anniversary of these »tiny black pests« this year. Are your going to organise a party or create an anniversary comic strip?

Frankly speaking, I have had quite enough of the Minis. I still adore all of the personal things in them, for there is so much of me and my father in the characters of the Hedgehog and Professor … but all that nagging with some kind of pseudo-sophisticated philosophy has really started to rustle my jimmies. We always show the least tolerance for what we used to be.

I have re-read them all over again recently and I fell in love with them for the second time. I remembered how I used to run during recess to the bar next to our school to read your creations.

I find it absolutely awesome that you people, just slightly younger than me, could get so enthusiastic about these comics, it really is an extremely pleasant feeling. Do you know how I used to make them? First, I read one of the books from the Pogo collection by Fantagraphics, then I sat down and came up with an entire season, approximately twenty Sunday pages, which would last me until summer when I was replaced for good by Robert Ilovar. The two of us used to sit in the same bar and show each other our comics, probably at the same time you used to go there.

I find it incredibly hard to believe that the later Minis were drawn with a brush.

It is true, I have truly mastered the brush technique by that time, I wanted to draw like Miki Muster (a famous & recently deceased Slovenian comics artist) and Kelly. Even Tomaž Lavrič didn’t believe me when I told him that the Minis were created exclusively with the brush. When I first started making them, I was 13 at the time, I would only create two images at a time, each on its own page, and it took me quite a while to really get the hang of it.

However, I am a bit tired of this process now. The use of a brush is very zen-like, you need insane concentration skills for it and if you were concentrated it will look great, but if you were not, it will look awful.

So, I’ve been using Rotring pens for a few years now, just to get over this demanding femme fatale of the brush. I did mourn and miss the added value of the brush, but I needed a little »peace in my soul«. I have managed to become friends with pens now, but I still reach for the brush when I need to do apply the washing down technique.

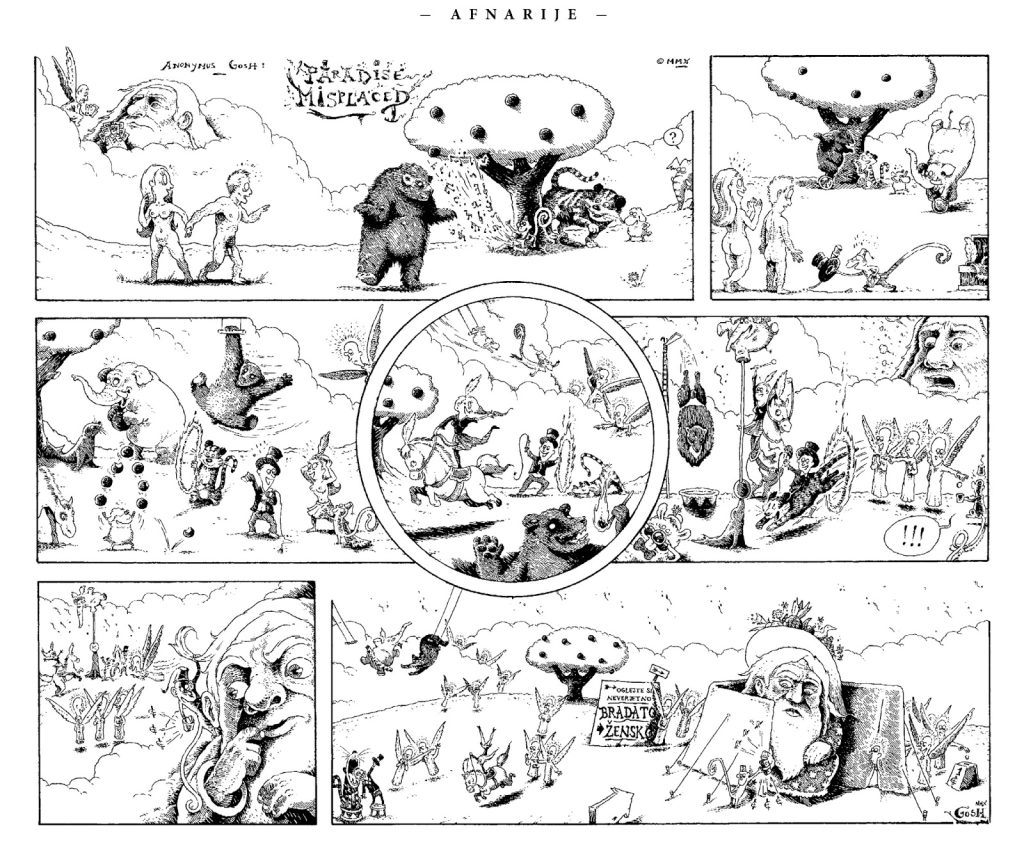

It seems that pens and Rotrings led you to the use of heavy crosshatching in Paradise Misplaced (Založeni raj). Did you feel your »bare« drawing lacked something and thus filled it in with shadowing?

No, not at all: the brush allowed for a certain minimalism that I used for several years, creating images with a few expressive strokes, which is more or less the same phase I’m in now. But then I got bored with this and wanted to create something more precise, something fetishist, something that needed vast effort. So, for a few years I focused on what later culminated in Paradise Misplaced. I pushed the dynamics to a certain level, but then I started craving for slow holy graphism. My intent was to prevent the reader from reading too quickly, to force him to stop and read the drawing closely and thoroughly. Fetishism, religion, ritual, all of these thingies.

Ilovar, whose minimalist design was in full swing at that time, disapproved of this, saying it was impossible to read my work on a jumbo billboard, and I replied that this was precisely what I had in mind, that this was for everybody who didn’t like billboards, everyone who wanted to stop in the middle of this hectic franticness and immerse themselves into the infinity at the bottom of a newspaper page. The lower second floor of Oklepaj followed this idea meticulously. If you don’t take your time (and a magnifying lens), you’re going to miss out on something and that was the whole point. You can move quickly and consume comics fast, but you will miss out on something.

This was followed by a complete change of heart. Your recent comics are drawn in a very quick manner. Was this a deliberate decision?

At this moment I prefer the opposite: quick dynamic drawing, fast consumption, hyperproduction. It’s a kind of an antidote to the previous phase. To explain it in simple terms, fetishism became its own purpose and a source of pain instead of pleasure, so something had to be changed. In this sense, the interviews conducted at the Stripolis events with Vives and Boulet who both draw at lighting speeds, were true eye-openers. At the time Vives stated: »People say my drawings are ugly, but they apparently confuse comics with illustrations. If you spend a mere three minutes on a drawing, you have no problems replacing it with another if you notice it damages the dynamics of the sequence.«

The drawings in comics gain their character only through the sequence, which allows for a quicker and more effective way of reading comics. On the other hand, fetishism has its own perks: I still like Paradise Misplaced, as well as all the Moebiuses, Crumbs and Millionaires that fascinated me at that time.

Newspaper comics are an extremely demanding form. You need an idea worthy of publishing every week, you’re always in a rush, you run out of space …

That’s all true, but I remember that I found these limitations excellent. You have limited space and time at your disposal, you have fixed characters, and you have to create something from what you have at your disposal. It’s a great exercise in the use of limited space and resources.

What about the proverbial newspaper haste?

That wasn’t a big deal, I even discovered I liked it. I like deadlines, because they give me a limitation that helps me avoid spending infinite time complicating.

What about your passion for travelling, this must’ve suffered during that period? Were you able to stockpile comic strips for future publication?

One time, while working with Oklepaj, I managed to create a dozen episodes in advance, because I was about to take a long trip to Africa to celebrate the end of my studies. I hurriedly drew comics six weeks before the trip, under the pine trees on the Croatian island of Cres. I used to get up at five or six in the morning while the rest were still asleep and make comics so that I could join my friends later on the beach and in the sea.

But then the newspaper Delo replaced my editor and the new editor dismissed me along with a whole bunch of unpublished comics. Sob.

And now they’re buying the rights for Garfield for peanuts.

My friend Janko Plešnar recently said that this was a superb metaphor for the current state of the Slovenian media and the general spirit. One fat yellow cynical blob that is constantly whining and complaining.

It’s a shame that Slovene artists have no more newspapers in which they could publish their comics. That used to be the only way of making a living by creating comics that were published only locally.

The Metamorphose Anthropomorphise is a story that sticks out. You’ve published the first part of the »ducks with dicks« in your first book collection entitled Beštije, but you continued it after several years in this book. What has gotten into you after all these years?

This particular story somehow wanted to tell itself on its own. At first, I only had the first part of the first chapter in which Bruno goes to a bank and hits on the bank clerk. This was supposed to be all, some kind of a surrealist genre parody of a TV soap-opera.

But it does originate from a joke that it was a comics with subtitles, right?

Yes, TV was my main reference. This was also hinted by the curved frames and static cadres in the first part. Somehow the gangsteresque Disney style, Italian language and television came together in a wacky coherent whole.

After finishing these three pages I started wondering what will happen next. So I wrote that part with coffee dancing. When the characters forced me to create the third part, I simply killed the duck, thinking it was all over. But a year or so later my upstair neighbours started to get on my nerves so much that I wanted to chastise them in a comics along with all similarly-minded regressive fellow Slovenians, so I said to myself: »Oh, Bruno the duck could fuck them up as an outsider and as such he would evoke the worst in them!«

So you chose Lakotnik (editorial note: a famous slightly dumb character from a Slovenian comics created by Miki Muster) to stand in for a typical Slovenian?

Yes, and this came along well as a Disney-meets-Muster drawing, especially with Muster’s cowabunga-styled and fruitlessly sexy universe, so I was already rejoicing over the excellency of the end results.

But … I lost all the excitement in a mere seven pages or so. A few years later I agreed to complete the story for the Mladina magazine and the deadline pushed me into completing two pages by Wednesday evening. And this is often the only way to really finish something.

And then you drew Bruno’s youth and the epilogue of the comic, which is, at least in my opinion, one of the best endings in Slovenian comics.

The last part had a life of its own and wanted to be told. I was driven by the question as to where had this duckling come from and I was inspired by the atmosphere in Italian neorealist cinema, Bicycle Thieves and the like … basically movies my parents used to watch when I was a kid. So, when I finally told that part, Bruno shut his mouth for good. He stopped whining about the continuation of the story, probably because he got such a nice ending. However, this poetically badass ending inspired me to start thinking intensively about Animal Noir.

Was this why you and your co-writer Nejc Juren created Animal Noir? You and Nejc were the first Slovene artists to be published in the USA. How did this happen?

We started off by writing a concept and the initial 15 pages of the comic, to which we added a synopsis, i.e. we had the entire pitch. We took it to the festival in Angoulême, but nobody gave it a second look.

Then I went to Barcelona, mostly for private reasons, but a comics salon was taking place there at the same time. It had a great pitching system: you left your pitch in a box and if the editors liked it they invited you for an interview. However, the interview was not with a sub-editor, but straight with the main head of the house. This is how we got an appointment with IDW and Ted Adams, who founded the publishing house with four of his friends fifteen years ago and who remained the one and only boss for all this time. At that time he was going through a phase of being fascinated by European comics, and he decided to take a risk with a few more European-style comics that didn’t fit into their line of franchise comics such at TMNT, My Little Pony and Transformers. If there was someone else from IDW, they would never have accepted the comic. I think Ted probably ran it on a personal whim, to take a breather from the turtles and ponies.

What was your collaboration with them like?

The great thing about it was that Ted was our editor all along, which was a huge honour since a head of such a huge corporation – which also makes TV-shows – doesn’t usually edit publications.

We agreed on a pilot series consisting of four parts. If these took off, they’d continue the series. However, the sales between 2000 and 4000 issues were too small for such a company (as opposed to the author’s publishing houses for whom these numbers would be a great success, even in the USA) and the series was cancelled. However, we got good feedback and the fact that the whole world is reading you and that you can listen to Australian podcasts about your work are awesome. As was the opportunity to work for a few months, creating 20 pages a day, knowing that they are going to reach a wide audience.

How come you decided to create it in colours and with such a saturated palette?

Sadly, I was told in the previous meetings with the French editors that colours were indispensable. When I got together with Nejc I even said »Let’s have a whole team and find a colourist!« But then I had to learn how to colour myself. As soon as I started I realized I was avoiding stronger hues, so I raised them deliberately to make it harder. One can easily hide behind pastel tones if they’re not skilled enough. At the moment I have had enough of colours and I’m working on a black & white comic.

Tell us more about it: what are you working on now?

I’ve been making pitches for half a year, I have five of them now. Since none of them resulted in a contract, I started working on the first story. I’ll continue working on comics for a while, without thinking about a foreign publisher. In the meantime Nejc and myself started working on a new comic that takes place amongst the student population in Ljubljana. A guy falls in love with a girl who returns to her native village every Thursday so that she can see her boyfriend (from when she was sixteen). The three days a week she spends in the capital make her look very lively and fall-in-love-worthy, but when the weekend comes she always runs back. This is the main story from which several of our favourite threads hang: local scenes at Metelkova, around Maksi, at the railway station, in old bourgeois apartments, etc..

Apart from creating comics you also write a blog (for online Literatura, previously for online Delo) which is a combination of text, illustrations and comics. Sometimes you start with a text, sometimes the whole post is in comics form. What’s your creative process for this like?

I’m constantly writing down all these tiny ideas about things I could be writing about and it’s always on the last day of the deadline that I decide which one to choose. In most cases it’s an event from 14 days ago, something that defined this period from the perspective of the last day before the deadline. Sometimes I write down an idea a week in advance, but when the deadline comes I notice that there’s something else that has grabbed my attention. It needs to be something that means a lot to me, something that comes with an emotional charge. Sometimes, when I am left without an idea, or when I feel generally indifferent and don’t feel especially inspired by anything, I simply go through my list of old ideas and create something professionally: I realize the idea with the best means available.

I’ve always wanted to do something autobiographic, but I had no idea how to address it, how to draw myself as I can’t do caricature portraits. A lot of the autobiographical comics I’ve read went on my nerves because I found them either too self-critical or too pompous.

This is the challenge: how to present something very personal to a broader audience, not merely to the people who already know me. I’m often told by the people who know me that I’m doing a good job, always adding that my blog feels very non-specific and not only about me and my kid, but about some ordinary living beings they can identify with.

What about »Izar the Initiator«? You’re good at creating sparks and you’ve ignited a series of comics events titled Stripolis, Stripolisfest (nowadays called Tinta), the Striparna comics shop …

Yes, I often have a strong idea as to what would be great and notice that nobody has the energy to start these things, while I like to start-up things. So I start them. I take them to a point and then I hope that someone else will take over. It worked with Tinta, partly with Stripolis and at least temporarily with the Striparna shop.

The other reason behind all of these initiatives (apart from the frustration over how little is required to start something nice that I’d love to have but nobody is willing to start) was quite egoistic. I just couldn’t work in a vacuum anymore: I needed feedback from readers and co-creators. I wanted to have a venue where comics would be promoted, and of course that would also mean my comics, and I wanted to have a place where I could learn what is happening in the world of comics right now, like I was able to do in the past in Kazina. Until then I only read what I usually read (Crumb, Krazy Kat, Moebius), but since then I’ve discovered many new comics and was inspired just by browsing through the hot new titles and reading them be-hind the counter. I met Nejc in Striparna, Boulet and Vives showed me a new way to draw in Stripolis and all of this is great. And if it helps others, even better!

But you’re also capable of maintaining the flame. You’ve dedicated several years to each of these projects.

True, but this is my maximum. Then it needs to become a real job for someone who has been in cultural management for at least five years.

I have the feeling that Slovenian artists don’t have the luxury of merely being present on the scene, making comics, but we also need to co-create the scene.

That’s true. But it’s nice in a way … as long as it doesn’t take too much of your time, it’s great. I’ve found it useful at times when I had no real inspiration for drawing. But when I was commissioned to create Animal Noir it got in the way, because I wanted to draw 5 days a week. Now it fits me again, especially the pop-up Striparna shop (editorial note: Striparna is moving from Mestni trg to Vodnikova domačija and will be operating on a monthly basis).

We haven’t even touched the subject of philosophy yet. I find it fascinating that you were studying philosophy at the time you created the Minis, and then you went to study painting at the Academy of Fine Art and Design. I remember how Tibor Kranjc, your remote cousin, was amazed when you finished both studies. How were you able to do all that?

Somehow, I was doing well and I enjoyed both studies. I think I would choke if I stuck to a single study. I was very hyperactive at that time, I liked being in constant motion and I liked to brag about my combination of partying and hard work.

What?! You even had time to party?

Sure, yeah, work hard, party harder! I went to most of the exams for my philosophy degree with a hangover, because that would make me relaxed while answering the questions. At the time I lived with my girlfriend in a small bedsit in Prule and every Thursday or Friday we had visitors in our place drinking until the early morning hours. I don’t know, apparently I have a bit of a promiscuous character, you know, it seems I need several things at once in order to avoid becoming smothered by a single one. This got harder as I grew older, so I deliberately minimized my world. I’ve totally done away with philosophy, for instance.

But before that you obtained your PhD in philosophy on the topic of the holy and the funny, and you published your findings in a book.

I’d love to turn it into a comic story because it’s a very interesting topic, and nobody wants to read the book: it’s very communicative for a doctorate thesis, but it’s still a doctorate thesis.

Let’s switch from philosophy to psychoanalysis: what’s the deal with all these dicks that you keep on sending us to publish?

I used to draw dicks at the university for years, party as a reaction to the mildly motherly approach from prof. Metka Krašovec, as an attempt to provoke her. But obviously it wasn’t about that, as I’m still into drawing dicks. I don’t know: dicks, tits, hitting, running, gorging on food – I like infantile ancient things, very specific but also abstract. They fit perfectly into comics which are also both ancient and infantile, the most specific and the most abstract of all arts. Smudges, big noses and feet, bold letters, visible time, while symbols, are also a totally abstract perception of speech and time, a stylization of everything. The same applies to dicks, they’re very specific and very abstract.

Would you like to add anything to the Neptuna and Lady Tomcat comics that are published in this issue of the magazine?

Both are pure improvisation, each was born from a single image that kept on evolving. Neptuna was at first merely a drawing of this hyper-virile badass sailor who was pushed so far (he eventually fucks everyone, even men and fish) that he becomes his own opposite. Even with his dick cut off he goes on to rule as the dark goddess of the deep … The first sentence from the story comes from a Monty Python skit that used to occupy my thoughts in which Eric Idle is reading children books that become perverted after the first two sentences.

Lady Tomcat toys with similar paradoxes. You never know what’s really going on: is this cat a woman and the whole tribe basically brutally rapes her? No, wait, it’s about this hyper-virile gorilla-type guy with a giant dick that gets raped by vulvas. In the end it becomes clear that these are two organisms that live in symbiosis, so you become even more confused and all that violence turns out to be merely a manner of reproduction. It’s all fun and games. There’s a lot of my fascination with biology in these comics, just like there was with Animal Noir. Same same, but different.

They look really nice. It was amusing to read through all that onanism, but I couldn’t shake off the feeling that I didn’t get it completely because I’ve never read Freud.

Teehee. There is no Freud in there and knowing his work wouldn’t help you in the understanding of the comic.