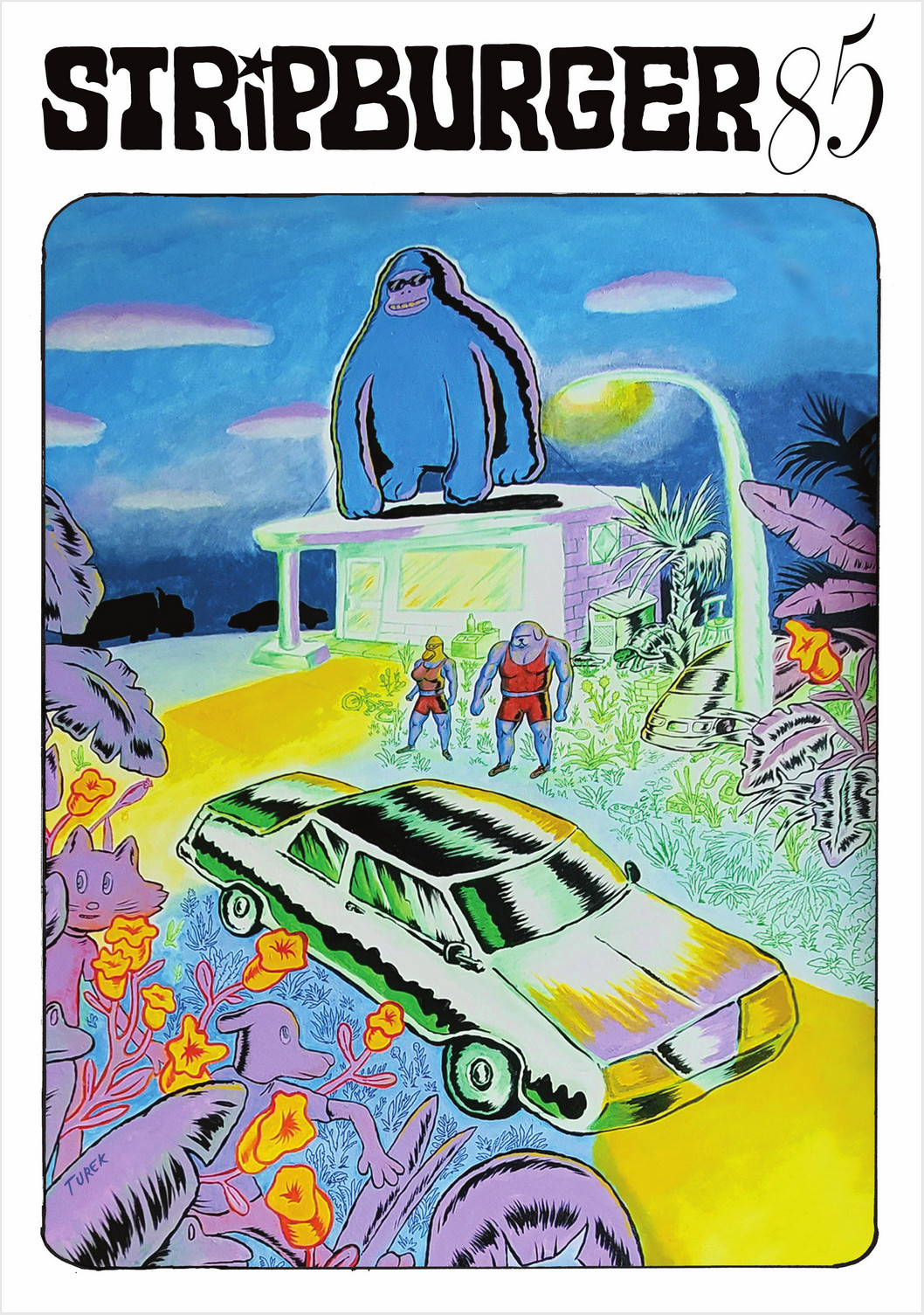

ATAK (Germany) – interview, Stripburger 71, May 2018

I visited him on a Friday afternoon in his home in Prenzlauer Berg, the bohemian and artistic quarter of East Berlin. During our conversation we were surrounded by hand-carved African masks and images and figurines of Hergé’s eternally youthful Tintin, created by his greatest fans. Among the myriad of things were also dozens of old wooden nativity scene figurines, at least a hundred years old if not more, bought somewhere in Tirol. His studio is a cabinet of wonders, just like the one from The Toy Box exhibition by Georg Barber a.k.a. ATAK (1967) which was held in the Kapelica gallery in Ljubljana way back in 2000. ATAK came to Ljubljana with an old suitcase full of figurines and toys that could instantly be transformed into a magnificent exhibition gallery. The former punk and dedicated professor of illustration at the Burg Giebichenstein – University of Art and Design in Halle, Germany, mastered the retro-mix style long before it became popular and trendy. He abandoned comics-making a decade ago and focused on illustrating and painting, but his works still feature, alongside picturesque plants, birds and other creatures, a bunch of different comics characters and visual quotations from the history of art, pop culture and other fields: from Tintin, Mickey Mouse, Popeye, the Simpsons and King Kong to motives from old illustrations and romanticist landscape paintings. Ever since he began his career he has been playfully crossing the borders between various media, passionately exploring and collecting all kinds of material, from original comics panels to fan art and folk art, always discovering anew a fresh, eclectic and unique way of expression. ATAK is a pleasant, interesting, eager and knowledgeable conversationalist with whom I could have spent hours in conversation if, two hours into the interview, another interrogator – the third of the day, and it was only 1PM – hadn’t rang the doorbell. (Tanja Skale)

If we start by looking into the rear-view mirror: you have a rich and diverse artistic path behind you. From an East-German punk rocker and an alternative comics artist you have become a renowned illustrator and university professor. How would you describe your career in a few sentences?

I never planned it to be like this. I am originally from East Germany where the comics scene was virtually non-existent. We only had one comics magazine, Mosaik, but this one was really good. Occasionally we would get to read Asterix or Lucky Luke or something like that, whenever someone managed to smuggle a copy across the border. As a child I was fascinated by comics and I loved reading them. Then, in 1989, a few friends and myself started publishing a comics fanzine entitled RENATE in Berlin. It was one of those comics fanzines with a true punk background and attitude, much like Stripburger in the 90s, which we came to know about after meeting Igor Prassel (a former Stripburger editor) and others. However, we never got any money from all that punk, even though RENATE was all in black & white. Me and my friends were interested in what was happening with the comics medium, in the different ways it could be used, but nobody at the time cared about comics as a form of artistic expression. At the time I was creating comics only for myself. I had a small publisher, but I was also making silkscreen prints, designing theatre posters and similar just to survive. Things began to change only after the year 2000 when I got the opportunity to create comics for newspapers such as the Berliner Zeitung and Die Zeit. That’s when I started to create comics in colour, for I only created black & white ones before that. Then I moved to Stockholm where colours truly began influencing my work, and my style, which previously resembled graphics, also changed. In Sweden I spent time with my family, I was surrounded by nature and I had a completely different feeling than I had in Berlin in the 90s when I was surrounded by techno culture, clubs and all that explosiveness … I had time to think about what I wanted and I was becoming increasingly interested in colours and painting … In 2007 I was invited by a publisher to illustrate my first book for children (Comment la mort est revenue à la vie, created after the story by Muriel Bloch, Éditions Thierry Magnier) and from that time onwards I became increasingly into this. So, my path led me from a B&W punk style to this here. It’s not that I’ve grown up (laughs), I’ve only become more fascinated by colours.

Why did you stop making comics? What changed?

It is hard to explain this in a few sentences. At first, nobody was interested in comics and when someone from the artistic circles asked me what I was doing, I’d answer comics, of course, which was followed by the question whether I could make a living from creating comics since nobody cared about them. For all of us who created comics at that time, and for me especially, this was a kind of freedom in the artistic sense. However, this also changed: in the new millennium an increasing number of Anke’s (Anke Feuchtenberger) and my students begun creating comics and even German newspapers started showing an interest in them … Years ago, comics used to be the »ugly duckling«, while nowadays everyone knows them, with graphic novels they have become a type of literature for grown-ups, they grew up themselves, in a way. This is why I’m not interested in them anymore. If you ask me comics have lost something they had in the beginning … they are no longer provocative. Secondly, making comics requires a lot of time and discipline. I am very proud of my colleagues who create big books with 400 pages. It takes a lot of time to create the story, research everything, make the storyboard, and then draw everything … I don’t have the discipline or time anymore. I also think I can tell stories with my paintings just as well as I could with long comic books.

I like reading comics, but the medium no longer fitted my work: I had to develop a story, do a lot of research and thinking, and in the end the comic only had approximately 5% of my idea. I don’t know, maybe I’m not a good storyteller or I’m not good at putting the story onto paper … but I do like the idea that you can create your own world using merely a pencil and paper, the fact that anyone who wants to do it, can actually do it at home. If you want to paint you need paints, a big room and so on, but you don’t need any of this for comics – this is what I like about them. However, I have finished with this story (laughs).

Let’s stick for a while to your comics period … Which artists were (and still are) the greatest influence?

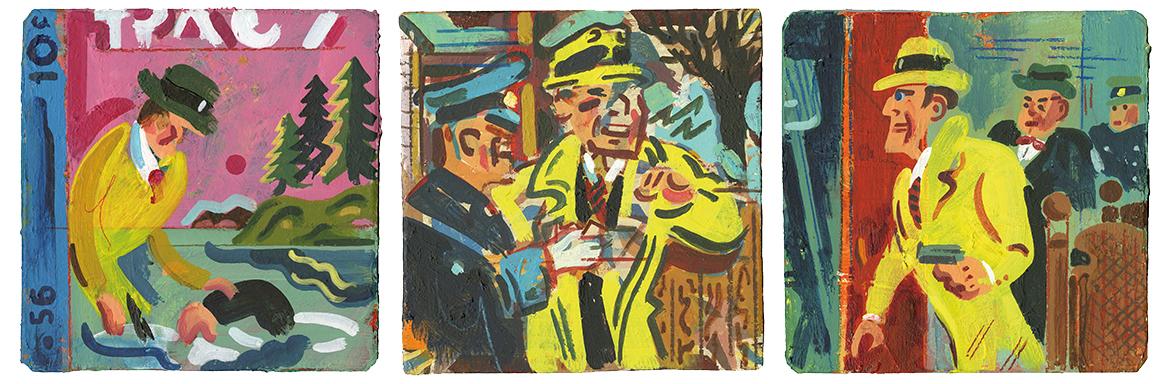

Gary Panter was a huge influence on both me and my generation. He created Jimbo in the 1980s and I think this still remains a contemporary style of drawing comics. His comics were punk rock. All that freedom was a great influence on my work, it showed the freedom to do whatever you wanted. Earlier, comics were like Tintin, for example: you had a narrative, a hero whom you followed throughout the story, a clear structure, a frame setup … Gary Panter turned all of this upside-down, and this was great. However, I’ve never read his stories, I was always fascinated by his images, the graphic part of his comics. He had connections with the art world, he collaborated with artists such as Keith Haring and Basquiat … at the time Gary Panter was the greatest influence on me, but now … Lately I’ve been working on some kind of a »fan art« project dedicated to Hergé and his Tintin. Tintin is a classic European comic, so to contrast it I used Dick Tracy by Chester Gould, who was never very popular in Europe, but was a huge hit in the USA in the 1930s … Today, when I look and browse through comics, I always end up with Dick Tracy in the end (laughs). It has everything I like in comics, it looks great in B&W, the characters, the energy, the narrative style … all are incredible, I really like this timeless noir style! This is the main reason I’ve started this »fan art« project.

Sounds interesting. Can you tell us a bit more about this project?

Since we didn’t have comics in East Germany, I started making my own comics during my teenage years, for which I would use characters such as Asterix or Lucky Luke. I used to draw 48 pages and practically make my own copy of the comic, just like kids do it today with mangas: that’s »fan art« too. It involves a peculiar way of thinking and drawing: not drawing what you see in the world, but what you see in comics in the way it is drawn in comics. I liked this feeling and I wanted to get it back.

For the last few years I’ve been working on another project named Der letzte Mann (The Last Man) with which I’ve explored war themed German folk and amateur art: from children’s drawings, figurines and toys of soldiers to soldiers’ and P.O.Ws’ artwork, different visual processing of traumatic war experiences … Similar collections of war themed folk art can be found in Belgium, England, France and USA, but not in Germany, since this remains a taboo topic because of the two world wars. When I began with the project, some people were disturbed by it, you know, because of national socialism, racism etc., but I found it extremely interesting and essential to inquire about the consequences wars have on artistic creation. Thus, I gathered different works on the topic and displayed it as an exhibition in a gallery in Halle. This year it will be presented in a major German museum, next year in another one … In short, this is a demanding, complex and long-term project that has no connection to my own artistic work, but I think it is very important for the German society. I got tired of it and thinking about what to do so I’d love to regain the feeling when I was a teenager, to re-discover the joy of re-creating comic worlds and characters. This is how this project came to life.

Right now my new publication is being printed in England, in the form of a magazine in which I recreated the covers of all Tintins and visually retold the story from each album in the form of a single-page comic. Hergé created 23 albums, the last one was left unfinished in the sketching phase, so it was published posthumously. In short, I’ve presented all Tintin publications in a single magazine as a sort of homage to this legendary comics hero. Usually when I draw, I take a little bit here, a little bit there and create my own world out of this, but in this case I was working directly with Hergé’s material and my publishers, the Belgian Fremok and the German Lubok, were seriously worried about copyright infringement since the Hergé Foundation is very strict about this. But this is basically the main idea behind »fan art«. I have a huge collection of »fan art« items dedicated to Tintin. What I like about »fan art« and comics is the idea of creating characters such as Tintin, Dick Tracy and Jimbo who then get to live their own lives and you have no control over them. For example, my collection includes a figurine of Tintin from Africa and I don’t think the person who made it ever actually read Tintin’s comic books. While in Belgium I met a guy who made several thousand drawings of Tintin and I bought a few from him. I just love how the story and its characters get to live their own lives in a new way. This is where the origins for my »fan art« project which connects Tintin to Dick Tracy in an exhibition entitled Fan Art, How To Be A Detective? created for the comics festival in Aix-en-Provence in France, come from. I wanted to show that the two heroes are similar: they are both detectives, both were born in the 1930s … This is not a very comicsy or artsy project, I don’t believe anyone from the artistic circles will show a great interest in it. This is my own personal project with which I hope to re-live my childhood feeling of creating copies and making »fan art« (laughs). I like the term »fan art«– it’s about art, but it also raises the question as to what art is in the first place.

I’d say you constantly tread the fine line between »high« and »low« art …

It’s true, I like it, but it’s not always easy. I don’t know exactly where to draw the dividing line … I like both »high« and »low« art, I like different things and I’ve always liked to cross borders.

Today I can say I’m an artist, but when I started with comics nobody in the art field was interested in them, so they represented some kind of a revolution, a space for freedom. But when I, as an artist, look at what happened to the comics scene with the arrival of graphic novels … I see that there are great things that I like, but sometimes it doesn’t feel enough … Hmm, how can I explain it? You asked me earlier about my comics influences: one of them was Jack Kirby, the creator of the Fantastic Four, and approximately twenty years ago I bought one of his original panels. Jack always used the same composition on each page, a grid of six frames. His work is wonderful, it is full of energy, there is always an explosion somewhere … He used to make six brilliant drawings on one page, but never gave them any thought while drawing them. This is what is different today. For example, in my last project dedicated to Tintin I was very quick at drawing covers and I spent approximately one day per cover. But it was a different story with the one-page comics, because each page has 12 frames, which meant 12 images or 12 days of work (laughs).

What I’m trying to say is that there are different approaches, different ways of thinking in art, comics and in illustration … In comics, less attention is paid to artistic impression, you need to concentrate on the narrative, the visual part is usually decorative. Some artists consider how to present a story in a different way, but in my opinion most of them are very conservative with that.

I’m not sure how much you’re into the contemporary trends in the global comics scene, but it seems that younger, up-and-coming generations are bringing with them a more experimental and more artistic approach to creating comics. Today, these have to be done in colours, riso-printing is all the rage now, as is a very retro style. The narrative comes second, if at all, it’s mostly about expressing a feeling or atmosphere …

It’s true, I’ve noticed this with my students. This is a small scene in which they make graphic fanzines and are not interested in storytelling. I think the difference between graphics and storytelling is very clear. If we look, for example, at Persepolis, we can see it’s visually quite boring, the drawing is very poster-ish, but the story is great. Satrapi is a great storyteller and his simple drawing style actually fits the story. If we look at Gary Panter and his Jimbo, the situation is different: each of his drawings is filled with energy and carries its own story. You have young illustrators who are great storytellers, but I can’t find anything visually new in their comics. However, it’s also true that I’m not up to date with contemporary trends.

I have great respect for my colleagues who create big books: when you open one you can instantly see the effort and work invested into it. When Scott McCloud published his Understanding Comics in 1993, the question arose as to what would happen to the comics medium in the time of internet and digitalization. Everybody thought comics would become mostly digital, equipped with sounds and whatnot, but nobody expected progress to turn into a completely different direction, into graphic novels. Now it’s important for the reader to have a comic book with many images, many pages, a story to follow and in the format of a book … Even the reputation of comics as a medium shifted completely over the last ten or fifteen years. The bourgeois didn’t care about comics at all, but with graphic novels, comics became literature, even in Germany, they are almost like Goethe in the sense »this is okay, this is a book, this is literature«.

But when I look at Dick Tracy … Chester Gould has been drawing one comic strip a day and an entire page for the weekend every single day for forty years. I am interested in his approach as regards narration: he had to tell the story in four frames, so he put a lot of attention into cuts and the temporal component of the action in his comics. With graphic novels you have many frames with which you can create an atmosphere and this can sometimes become boring: I feel one could leave out one third of the book since it’s just some talking heads looking at each other … Personally I find it a bit boring, but then you have good books and you have boring books, it all depends on the author. Maus or Persepolis are of course very interesting as regards their themes, but comics are also entertainment, action and adventure. I find this tendency for autobiographic comics that became popular around the turn of the century quite boring – many comics artists don’t lead very interesting lives and it can be very boring to watch and read about their boring lives. This led me to the idea of creating the most boring comics story in the world …

And? Have you made it?

Yes, nothing happens, it’s really boring (laughs). It takes place in a shop where a man that we never see meets a girl, buys three postcards and leaves the shop. And that’s it. It’s boring but it happens all the time, every day: someone comes to a souvenir shop and buys postcards. At least I hope the images are not boring. The idea for the story comes from real life: a souvenir shop in France where one of my friends has a studio. The comic includes three postcards with old photos from that same shop and the story of a woman can be seen in one of them. This friend told me the story of the woman’s unfulfilled love for a certain man, however, I got the inspiration from that actual space, the shop. And this was the last comics story I ever made (Kub, Reprodukt, 2008).

What’s the situation in the German comics scene today? Is it possible to make a living from creating comics?

It really takes a long time to create a big comics book and I’m truly glad that one can nowadays get a special scholarship to create comics in Germany. This was not the case in the past, you never knew whom to approach or whether comics were considered visual art or literature. Bestsellers such as Maus and Persepolis led to German publishers including graphic novels in their publishing plans. The results are sometimes lousy and poor because these big publishers have editors who have vast knowledge on literature but have no idea about what is good in visual arts. Naturally, sales also dictate the rules of the game: in Germany, a bestseller is a book that sells more than 50 thousand copies. One can easily reach this threshold with literature, but not with comics, at least not in Germany. On average the numbers range between three and four thousand copies for a comic book, which is good, but not enough for the big publishers. In short, things have improved, but comics artists still don’t have it easy.

When I started regularly creating comics for a newspaper in 2000, I was actually the first one to do this in the last twenty years. At that time it was an experiment, both for the newspapers and the readers, while now it’s considered something perfectly normal or at least imaginable. The younger generations have it much easier, but the majority still lives from illustrations. The situation is the same everywhere except maybe in France and Belgium. Creating comic strips for a newspaper allowed me to make a living from creating comics for the first time in my life, before that I had to earn rent and food money by working in a comics shop. Suddenly my comics reached a hundred thousand readers each week, which was a huge leap for me as I came from the underground scene. Prior to this merely a few readers found my books interesting, some liked them, some didn’t, which is normal … But creating comics for a newspaper changed everything. Of course, not all of the readers read the comic strip, but at least they had the opportunity to read it. And if they did, they’d forget it the next day, for this is the nature of newspaper comics. The stories were written by Ahne who has a great sense of humour, I only did the artwork because I was too afraid to address so many people at a time. Our comic strip didn’t have the constant characters as for instance Peanuts does, for the idea was to have different characters each time. (In 2002 avant-verlag published a selection of newspaper comic strips from the Berliner Zeitung in the book entitled ATAK vs. Ahne).

Let’s switch from your comics to your paintings and illustrated books. There’s always an element of surprise in your work when the readers suddenly stumble upon a familiar character such as Snoopy, Mickey Mouse or Tintin …You seem to gather references from a myriad of places and use them to create a unique eclectic mix. This invites the reader to linger a bit longer, to take their time, explore the details …

True, but it all depends on the image and its purpose. The idea of mixing comes from the hip-hop culture where you take a little bit from here and a little bit from there and make something new. When I, for example, create an illustrated book for children, I have a story, I have images and then I have a completely different level, the child’s point of view. An illustrated book is like a stage upon which several stories can take place at the same time, unlike comics where you have a sequence of images, one story that cannot have another one in the background or on another level. This is precisely what I like about it, but you don’t have to recognize all the references in order to understand the story. They have the role of special treats and don’t affect the main story.

How do you go about creating your works? Can you describe your creative process?

I start by sketching, but I never know exactly what will happen after that. With a B&W drawing you need to know what comes next, at least a little bit, since you start with one line and continue from there … but it’s different with colours. I often take my old works and work with them: if you take a closer look, you can see several layers… Painting is more about the process: it is about adding, covering or removing something, about the general feeling: »Ah, so I have something: I don’t know what it is, it could be a cat.« It’s never totally clear and I just love this process. In the beginning I used to build space with structure and patterns, for I come from a graphics and silkscreen printing background. But colour is like space, it’s like a sound that fills the space.

My creative process is long and tiresome, but then it’s more about the way of thinking, about the openness of the process. Creating comics requires a lot of discipline, you need to think about how you will guide the reader through the story … comics is like a prison, while painting is freedom, you can use your material over and over again… Of course, you can draw on a computer, add colours and all, but a painting has something behind it, something you cannot »fake« with a computer. A painting may seem great in a book but it’s not the same as seeing the original. The texture is different, as are the colours… A book is always merely a reproduction of the original work. My friend Blexbolex and I recently had an interesting discussion about what was an original work. His work is actualized only through the process of printing, thus he considers a book to be an original. The history of comics is familiar with this, e.g. Little Nemo’s original is a newspaper comics page printed in colours. The perception of what is an original can vary. Especially now, when it’s so easy to create and print something with the use of a computer. When it’s a global thing and anyone can do it, the original work, it’s materiality and it’s feel become much more important… Even my students are becoming increasingly interested in old techniques such as lithography and linocut, and in the process of printing, even though it is easier and faster to use a computer. I want to smell the paint, touch the paper …

Over the last decade you have created several illustrated books for children, which I believe are of interest also to adult readers. Do you use a different approach when you are creating books for children?

I only had this in mind at the very beginning, when a French publisher invited me to illustrate my first book, but never after that. I’ve never done anything for children before so I was a little bit scared. I asked some of my colleagues for advice and they told me I didn’t need to worry about it as kids know what is good and what is rubbish. The only rule is don’t show sex. Of course, sex is present, but in a different way. Comment la mort est revenue à la vie (How death came back to life) tells the story of Death which is feminine in French. While creating the character I had the Snow Queen with her cold-as-ice heart in mind. I’ve seen a theatre play with her when I was a child and I was totally fascinated by her: she was very cold, but also attractive, so I wanted to recreate this feeling with Death, who’s also not a one-dimensional character.

Your next children’s book was Verrückte Welt (Topsy Turvy World, Jacoby & Stuart, 2009) which you created for a German publisher but which was also published in several other countries. It’s an illustrated book that tells a story without the use of words, but it looks a bit like a comic because a mouse appears on every page.

The publisher had a poem about an upside-down world where everything was standing on its head and he asked me to illustrate it. I wasn’t interested in working with text and I didn’t have the time for it, so I thought I would create a book without text. Each page is one scene, one world, and you turn the pages and jump from one world to another. The mouse is there because I wanted the children to have something to look for, like a game of hide and seek.

But you did write the text for the Der Garten (The Garden, Verlag Antje Kunstmann, 2013) which you also illustrated? I found it quite lyrical, I’d say that you not only chose your images carefully, but you did the same with words, you carefully built a narrative rhythm and used it to create an atmosphere …

More than twenty years ago we used to have a garden and I created a small book, a very crude fanzine about that garden. I wrote the words myself, at that time I was fascinated by the language of Gertrude Stein which is both modern and poetic … When a German publisher asked me for a new book, I remembered this fanzine and story. This is how it started, but when I began drawing Der Garten, I actually had in mind my parents’ garden, and they are also included in the artwork, sitting in the midst of the flowering garden.

And your mother is holding a Tintin comic book in her hands.

Yes, even though my mother didn’t really read comics (laughs). She wasn’t able to, she had problems connecting images with words.

You’ve also tackled the remake of one of the most famous and successful German children’s books of all times, Shock-headed Peter (Der Struwwelpeter, Kein & Aber, 2009) which was written by the German psychiatrist, poet and writer Heinrich Hoffmann. How did it feel to address such a classic? I remember the fat cat with a red nose who smokes, drinks and pukes throughout the book … It seems like a rather untypical character for a children’s book, but then, the original is also not very children-friendly.

Creating this book was excellent fun. I was able to do whatever I wanted, it was truly liberating. However, it’s also true that this book wasn’t intended for small children. Fil, a comics writer from Berlin, who is these days better known as a comedian with his own show and a great sense of humour, dealt with the text and working with him was simply hilarious.

Shock-headed Peter is very popular in Germany. It’s an evergreen classic children’s book even though some stories tend to be on the scary side. When we started this project a lot of people asked us why were the stories so cruel: the answer is because they are stories. We started thinking about creating an additional chapter, the most boring chapter in the world where nothing really happens, just like in the most boring comic in the world (laughs). During my research for the book I bought many different editions of Shock-headed Peter, thus I have a whole collection of them at home. Amongst others I have a Danish edition with an additional story that has nothing in common with the others and doesn’t appear in any other edition, which is very strange. This led Fil and I to come up with the idea of creating something similar. The last chapter thus speaks about a boy from the present and nothing really happens. To make it truly boring, the drawing style also had to be boring, so the book only shows what is mentioned in the text, basically making the main mistake of a book illustration. Here you have precisely this: Justin is watching TV, playing games and wants to get a new Xbox console for Christmas. Christmas morning comes, he opens up the presents and gets the console he wanted. I tried to recreate really boring, plain and cold geometrical drawings that would appear to be computer generated. The last story in Shock-headed Peter is thus also an homage to the American comics artist Chris Ware. But it was really, really hard to create such boring illustrations (laughs).

Your recent works feature many flowers, trees and animals, mostly birds: owls and kingfishers. How come? Are you a big fan of Mother Nature and her creations?

When I published my Alice (Jochen Enterprises Verlag, 1995) my mother read the book. Of course, it is never simple when a mother reads her son’s work. She liked the drawings but she had a problem with the story which is characterized by the dark punk spirit of the times. Even when I look at them I find them completely alien. I cannot recall the situation I was in at that time, I only know it was very complicated. I had a different way of thinking and working in that period. Later, I think it was some 25 years ago, I had a creative phase during which I only drew flowers. Flowers are non-lethal, non-ideological, non-political, there’s no special story behind them. However, everyone has an attitude towards flowers and I used it in my work to attract an audience. My readers aren’t my family and vice versa, these are different worlds, but my aunt, who is over 80 years old, liked my recent books.

I think you can see a different world behind these colourful flowers, however one of my colleagues thinks that something dangerous is hiding behind them. I like flowers and animals. These motives originate from my childhood when my parents had a garden and I was in touch with animals and nature. But nature is never really clean, it always includes death. At first you can attract the attention with flowers, but there is something strange hiding in this world…

I remember the moment when I saw a kingfisher for the first time. I went out with my family and I wanted to take a photo of us by the lake when a kingfisher came flying by. The sun was shining and his colours were so wonderful in that light, those turquoise and orange hues, he was like a treasure or a diamond and I got the feeling that he was a work of art. It wasn’t just images, it was also the feeling linked to a certain moment. When I was illustrating a book of Gertrude Stein’s poetry entitled Ada (Büchergilde Gutenberg, 2005), I recalled this moment and drew a kingfisher. It also appears in the book Der Garten that I dedicated to my parents.

But, as you say, not everything is nice and okay in nature. Your most recent illustrated book Martha (Aladin Verlag, 2016) tells the story of the last known wild travelling pigeon that died in 1914 in a ZOO in Cincinnati, USA, its species dying out with it. Where did you find this story? Should we read it as a subtle criticism of the modern times and society, of our attitude towards nature and our excessive exploitation of the natural resources?

I found the story in the National Geographic magazine. I was fascinated because it is a true story and I am also fascinated by what is happening in nature as a result of human activity. During the first reading I was taken away by the image of millions of birds in the sky, so many birds that it was as dark as night, for the sun rays could not penetrate through the flocks. I was fascinated by this image, this spectacle of nature and by the fact that these birds were now extinct. I went to my publisher and asked him whether he’d be interested in such a book. It’s a fantastic story, I cannot find a better one to explain what’s going on with nature and with our future … I believe it is important for everyone, even adults, but it is mainly aimed at children. When I started researching for the story, I discovered that it wasn’t completely clear what happened and who was to blame: it wasn’t only humans to blame, the story isn’t that black & white.

The process of creating the book was a long one, it took me three years to complete and I applied a different creative process. With Shock-headed Peter, for example, my friend wrote the text so I could focus on the illustrations. But for this book I had to write the text as well as draw the illustrations, and as it is based on a true story, it wasn’t always very easy. While doing this I kept asking myself who actually needs all this (laughs). When I’m creating my artwork, e.g. graphic prints, I know I’m doing them for myself and a small circle of collectors. But when you’re creating a book for the widest audience possible, especially for children, you start wondering who is interested in all of this anyway, for some children don’t even read books anymore … As an artist you don’t feel any pressure, but it’s different when you’re doing it for the readers. In the end I was pleased with the book, but I was also totally exhausted.

How does your teaching job influence your artistic creation?

I started off as an assistant professor in Hamburg, at the same school where Anke Feuchtenberger taught, this was between 2002 and 2004. A lot of young German comics artists studied in Hamburg at that time: Line Hoven, Arne Bellstorf, Sascha Homer … Then I stopped teaching and moved to Stockholm where I began focusing on illustrations and paintings … After I returned to Germany I taught for a year in the Belgian town of Gent, which was awesome: I had a nice collective, great students, both Brechts (Brecht Evens and Brecht Vandenbroucke) studied under me. At the time I also travelled a lot between Sweden, Germany and Belgium and I found it extremely exhausting. After that I accepted a professor’s position in Germany, first in Offenbach on Main, then in Halle in 2008. After that things changed – at first I found it hard to coordinate two jobs: create my work and teach. But now, with the arrival of the new generations of illustrators I can safely state that I’m not as interested in creating new books as I used to be. I’ve created several books and now my current or former students can continue my work from there. I like working with youngsters and I believe they will start creating great books. I can make a good living from teaching which gives me complete and utter freedom in my artistic endeavours, I don’t need to compromise. This is why I started the »fan art« project: I wanted to figure out what I really wanted to do, find my own vision… At the moment I feel the freest when I’m painting, even though I started in the fields of comics and visual narration. When I complete a large painting it carries the same amount of weight as if I would have created a book. I have an idea for a new project, but I still don’t know where or to which »scene« this will take me …

What is the role of music in your artistic life?

My artistic name is linked to music, for it comes from the name of the band I had in the 1980s. We only had three concerts, but East Germany wasn’t very punk rock anyway, it was more in favour of atonal industrial music. The name of the band was ATAK and following the fall of the Berlin wall, when I started drawing graffiti, I used that name to sign my graffiti and later I continued using it for the rest of my works. At that time I mainly listened to punk, ska and reggae, but now I create a special mixtape for each project. As you can see I have a whole bunch of cassettes here, but now I just do them on the computer. I discovered this was very important for me. When I’m teaching I sometimes find it hard to switch back to my own creativity because it’s fundamentally different. I use a wide variety of music to switch back to my production phase: from jazz and punk to hip-hop, the Beastie Boys and electronic music.

Each of my books has its own mixtape and a specific sound. For example, while I was creating Alice, which has a very graphic drawing style, full of small halftone dots that took a long time to complete, I listened to a lot of electronic music. When I was creating Martha, the soundtrack was more melancholic, in consisted of a lot of classical music and movie soundtracks which were constantly on repeat, but during the Shock-headed Peter phase I listened to hip-hop and punk. Each book has a different feeling and a different atmosphere.

I need music while I work, but I don’t concentrate on it. I find it impossible to listen to the radio, as that would be an intrusion of reality into my world, instead I use music to temporarily move into my own world. I would say music is important in my life even though I don’t create it. I occasionally DJ, but only for fun, and I attend a lot of concerts with my teenage son. Music is definitely the most important secondary thing in my life. But I think this is the case with a lot of illustrators and comics artists: our work is lonely and it takes a long time, so you need something. Music fills the space and makes everything different. I need my space and music, but I also need the sounds from the environment.

You’ve been living in Berlin for over three decades. How has this city influenced your work?

I grew up in Frankfurt on the Oder, a small provincial town close to the Polish border. At that time it had approximately 85.000 inhabitants, maybe ten punk rockers in total, and everybody knew us (laughs). I’ve been living in Berlin since the 1980s and of course the city has changed a lot during this time, even for me personally, but it’s still my city. Nobody is interested in you here, nobody interferes with you, you can walk the streets in your pyjamas and it’s perfectly fine, there is no dress code. I cannot be creative when surrounded by nature. I have a small cottage by the lake but I can’t work there. I need Berlin, the traffic, the noise, the pulse of the city, the possibility to go for a beer in the middle of the night, to the movies, anywhere … I need all of this if I want to be creative.