Gašper Rus (Slovenia) – interview, Stripburger 69, May 2017

At Stripburger we know Gašper as a comics artist, but his Behance profile reveals that he is primarily an illustrator and only thirdly a comics artist. His reasoning behind this skewed order of occupations makes a lot of sense. Professionally, being an illustrator sounds less exotic than the latter, so you may avoid the inevitable question: »Is it possible to make a living from that?« Our laid-back conversation with one of Slovenia’s most prolific comics artists took place in Stripburger’s library, in the warm embrace of comic books, where Gašper used to be the editor in chief for many a year. I still remember his last editorial meeting, in which he told me he wanted to spend more time making his own comics, rather than editing other people’s. Now, a few years later, he is proving the skeptics that it’s possible to make a living from drawing all day.

Gašper is constantly attempting to break the stereotypes that surrounded his work in the past. No more ‘Aloha, Gašper’, ‘Paperhanger’, or, more commonly ‘God Fearing Gašper’. He does this with persistent self-reflection, self-irony, and stubbornness. He is a perfectionist, who often exchanges nonchalance for detail, integrity and rigor. He often attempts to swap cynicism with humor. He always completes his work in time and he even arrived to his interview before the two interviewers (Mimo, NE).

Gašper, tell us: How did you become a part of the comics community?

I have been making comics since I was very young. I had a whole production system back then. I would go to my grandma’s house with my collection of blank papers, she would sew them together with her ancient Singer machine, and I would write my story (dictated to adults in the earlier days) in a homemade booklet that I could illustrate accordingly.

I started drawing my first comics even before I went to primary school. I was about five years old at the time. That was the time I became aware of comics as a form in which I could express myself. I distinctly remember a Miki Muster comic book that my father brought and this was the transformative work that pushed me to go out on my own, although I probably saw the works by Marjan Manček and Božo Kos in Ciciban (a kids magazine) way before that.

I was presented with my first semi-professional offer, which I carelessly rejected, during my high school years. It came from Pil – a magazine aimed at high school pupils. They didn’t have the space for an entire comic, so they only wanted an illustration, but at the time I thought there was more room in our country for comics and illustrations alike.

Did you want to be solely a comics artist at the time?

Yes. I told them I’m not considering illustration and that I want to be creating comics. A few years later, while I was a painting student in art school, the Pil story repeated itself. However, this time I sent in my illustrations and they were published.

Even though you don’t like painting, have you ever considered painting comics with acrylic techniques, similar to Jerry Moriarty?

I have to correct you. I never said I don’t like painting. I love painting, I just don’t see myself as a painter. I haven’t created a single painting since I completed my Painting studies at the Ljubljana Academy of Fine Arts. I probably won’t paint a comic either, although I like to leave my options open. I experienced the entire Academy studies as extremely uncomfortable. It was a wrong choice. There wasn’t any chemistry between me and my lecturers, or me and my classmates. You can’t truly develop in an environment like that.

Haven’t you showcased this experience in your comics?

I did, but I merely touched the surface. The entire ordeal was far too complex for a short comics story. I could make a lot more from what I experienced. But, honestly – I know this might sound pathetic – it’s still a great trauma for me. I don’t really want to delve into my Academy experience.

Can we expect a Slovenian Art School Confidential (Ed. a short comics story by Daniel Clowes)?

I sure would not oppose something like this.

It seems that your stories are often autobiographical (for example, Encounter, Melania and Her Consequences, and Betrayal) or explore social themes (for example, The Swing and Death is a Cliché). Your work rarely touches upon fantasy stories (except perhaps your story in Stripburger’s Greetings from Cartoonia or your comic Through Time and Space). I assume this isn’t a coincidence?

Encounter is definitely an autobiographical comic. The other two are only partly autobiographical. Betrayal and Melania both have personal starting points but they eventually branch off into fiction. The two main characters are also only partially based on myself. I prefer to treat them both as entirely fictional. I would prefer to categorize Journey to Space and Idea as autobiographical.

You have also mentioned social themes. It’s interesting that the two comics that deal with society are both based on suggestions I received from other authors, namely Žiga Valetič and Željko Obrenović. I am not sure I feel personally connected to these themes.

How do scriptwriters interested in social themes reach you?

Recently, the publisher Žika Tamburić (Modesty Comics) found me himself. He was looking for comics for a collection of Obrenović’s short stories, and he needed one more, so he recommended me for the job. Valetič, who was the scriptwriter for my graphic novel The Swing, saw gentleness in my style that really worked for his story. He didn’t want the comic to be expressionistic or grotesque, so he considered me a perfect fit for the project.

Do you prefer to use other author’s scripts or do you prefer to write your own?

I have noticed I have certain limitations when it comes to writing my own scripts. Longer scripts represent a great challenge for me, possibly a challenge beyond my capabilities. However, I have a strong will and ambition to create a new graphic novel. I’m just not sure I’m up for the task.

But when it comes to drawing comics adaptation of literary works, I am far more confident. I consider this a phase between illustrating other author’s works and writing my own. When I drew Limited Shelf Life, which is based on Vinko Möderndorfer’s short story, I considered myself a writer. I got to choose which excerpts I would use, and I could dramatize the story however I wanted.

Vinko generously gave up the rights to his stories so that comics artists could turn them into comics without his input. He wasn’t worried about what we would do to his work. However, I sought his advice once. I asked him: »Is this skyscraper where the story is happening the Ljubljana Skyscraper?« He told me I was correct in thinking this, but he also told me not to consider the Skyscraper a crucial motif in the story.

In the end, I decided to go against his advice and find a way of incorporating the Skyscraper into the comic, which made my life somewhat harder. At the time I was writing this, the café at the top of the Skyscraper had not been reopened yet. I could only go to the top of the stairs, where I would be stopped by a locked door. I really missed the view of the city from the Skyscraper’s terrace that is accessible only through the café. As I couldn’t go there at the time, I had to use old images I found online, but they didn’t look so good. If the café would have been open I could have taken photos or sketched there. As it was I had to help myself with the metal model of the city located on Prešeren’s Square.

Have you ever rejected a script?

I have. This was soon after The Swing was published. I won’t go into too much detail. A female author approached me and asked me to create a comic with a religious theme. I think she came to me because she had heard I am a practicing catholic, which was no longer true at the time. She just didn’t have the right information.

The premise of the project was actually quite interesting. The script was based on the true story of a priest with a difficult childhood. It was a kind of social drama with an alcoholic father who abused his family. In the end this priest wanted to make peace with his father. He didn’t hate him, he merely wanted to show his father he loved him. The story actually had plenty good dramatic moments. I just couldn’t identify with the part where the hero finds the meaning of life in priesthood. Religion was an important chapter in my life that I had just closed and I did not want to reopen it. I am talking about Christian circles, Christian youth, and so on. These were the reasons I gave the woman who approached me. But I think it came as a great shock to her and that she was really disappointed with my answer. I think someone must have presented me as this god-fearing Catholic kid, but in reality I am a rather cynical person. Well, not exactly cynical, but I just wanted to be done with that part of my life.

However, I wouldn’t say that I have distanced myself from Christian virtues or principles entirely. I still agree with most of them, I just don’t see myself with that religious group of people anymore. The whole thing was a social choice really. I simply feel I don’t have a lot in common with these people. I missed the open spirit when I was with them. There was no one I could talk about art with, let alone comics. In the end, I think that’s what really put me off.

What was it like to work on The Swing with the scriptwriter Žiga Valetič?

Even though I was younger than Valetič, I was more experienced than him, for this was his first comics script ever. In a way, I was the one leading the entire process of making this comics. I’m grateful that the script had a rather open structure. Valetič initially divided the storyboard into pages and frames, but I changed this format the way I saw fit and Valetič never attempted to restrict me.

I can share an anecdote with you: when I gave Valetič the first draft to look at, he was really worried. He had been thinking about his story in a very literary way and when he saw his script in comics form, he suddenly felt there was not enough text and he wanted to add a commentary voice which would function as a narrator. At this point I just had to say no. The comics mainly has a film narrative structure and his suggestion simply doubled the information that was already apparent in the drawings.

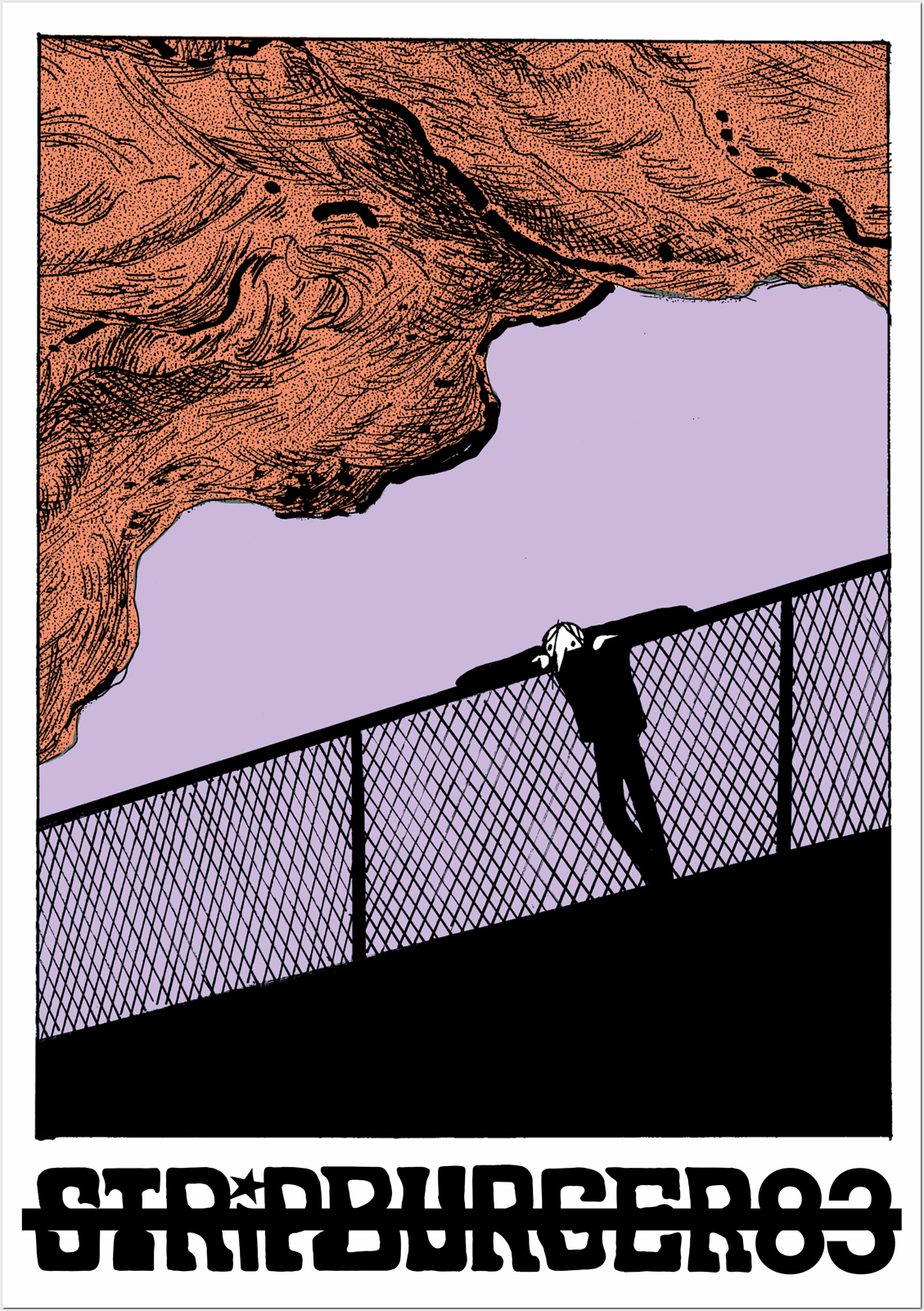

How come you decided to use the colour orange as the toning colour for The Swing? Isn’t that slightly unusual?

I rarely get input from both my scriptwriter and my publishing house, but there was one clear directive they both wholeheartedly agreed on: the comics needed to be more lively and optimistic, in a visual sense. When they told me this, I actually considered going full color, but the budget and deadline didn’t allow for this. The color orange was therefore some sort of a compromise. Since most of the story takes place on the coast in the summer, I felt orange was the ideal visual representation of a hot summer’s day.

The book was also translated into French, and published by the publishing house Des ronds dans l’O. What were the reactions to The Swing like in France?

I found four printed reviews and heard one discussion on a radio show. Most of the responses were positive. It is possible that the publishers kept some from me if they weren’t particularly flattering. I thought these reactions were quite subdued, which came as a cold shower for me. The French comics market is so big that even if you get published you’re merely a drop in a vast sea of artists. However, now I have a publisher in France with whom I can try out my future projects. It’s a small alternative publishing house with a clear brand. They are interested in engaging comics with social and psychological themes similar to the ones presented in The Swing.

I have noticed your comics are mainly about young people. You don’t really make comics about the adult life. How come?

I think these themes will appear in my comics at a later stage. I’m the kind of person who likes to take some time to reflect before I can really delve into a certain topic. I think the stories of my childhood and teens are just far enough from my current life that I can make comics about them.

You don’t think you’re being overly analytical?

Maybe, but on the other hand, creating comics takes a very long time. The entire production process is extremely protracted… So if I try to create a comics story about what’s happening to me today, by the time I finish it in three months, I will be in a totally different place and the comics won’t be up to date.

Can you tell me more about Melania and her Consequences? You started publishing your work online in 2015. Did you envision it as a longer comics story or a serial perhaps?

Melania has been on a break for a year. It was set up as a kind of experiment. I started drawing it without previously planning it. I have a general overall story in my mind, but I just draw as I go along. The initial idea was to draw it whenever I found any spare time, even if I only had time for a single frame. According to my initial plans it was going to be a mid length comic. I think I finished about half of it when I started working on an animated movie at the beginning of last year. My interest in continuing with Melania diminished greatly during this time, however, this isn’t the first time I’ve lost interest in a project. I’m still deciding whether I should put Melania in my Unfinished Projects drawer or buckle down and force myself to finish what I started.

When and why do you decide to use anthropomorphic animals in your work? Is this solely a nod to the comics tradition or is it something more?

I’m not sure it’s anything more. I’m simply affected by the influences of my youth: Miki Muster, Bill Watterson, Charles Schulz, and Jim Davis. Maybe anthropomorphism is a kind of a short cut to the personification of your characters, so the reader knows what kind of traits to expect.

Anthropomorphism is also a fun way of subverting stereotypes. For example, if you draw a frustrated and annoyed bear character, who is otherwise commonly portrayed as a cuddly and well-meaning teddy, you quickly succeed in conquering that prejudice.

One of the ideas I’m playing around with for my next project is a comic about animals that come to visit me in my studio while I’m trying to work. A lion, a cat, and a dog all clamor that I’ve forgotten about them and that they can’t remain alive if I stop making comics about them. One of the animals even tells me I have to resurrect my animal-drawing career because: »Gašper, we all know you’re better at drawing animals than anything else«. Of course I am very upset to hear that, but it’s definitely something I’ve heard before. I think comics with human characters present a greater challenge for me, and they give me more opportunities for growing and developing my creativity.

To conclude the interview, let me ask you this: You’re not a passive bystander of the comics scene in Slovenia. You were a long standing member of the editorial team at Stripburger and now you’re a comics reviewer and theorist. Do you think it’s important to not only be a part of the scene as an artist, but also as a thinker?

Writing about comics was how I penetrated the Stripburger circle and found my place in their community. I recently wrote a text for the catalogue of Slovenia’s comics over the last ten years. Looking at the text, I’m totally willing to put theoretical writing aside, or give it up completely. Every time I attempt to write I realise how difficult this truly is. If you want to be good at it you need to give it your all. If you want to write good quality reviews, you need to read a lot. You need to read everything that’s relevant and more. You need to read a lot of theoretical works and don’t even get me started on the amount of comics you have to go through. I simply think there are authors and critics who can do this better than me. If I didn’t have a drawing talent, I would find it acceptable to be a comics critic. It would be a way to channel my creativity. However, every now and then I do create comics and I do this rather successfully.