Katerina Mirović (Slovenia) – interview, Stripburger 70, November 2017

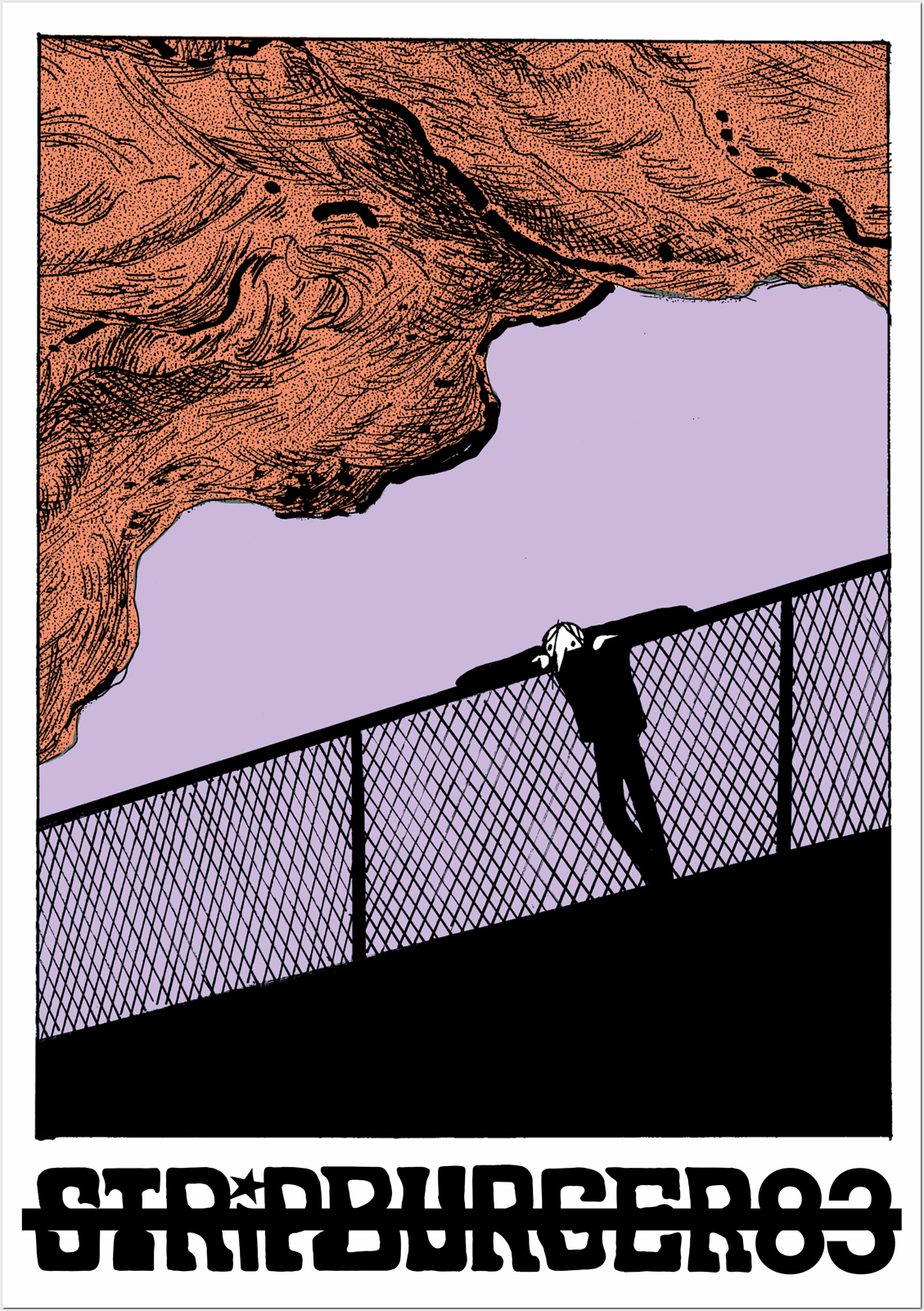

(excerpt from a comic by Tomaž Lavrič)

We are about to break rule No. 1 – no interviewing of current Stripburger members in order to avoid incestual promotion of ourselves. However, the 25-year jubilee is a perfect occasion to break this rule. We will take the spotlight from her kidney stone and focus on her persona. Although she doesn’t draw comics, Katra is the founder and a synonym for Stripburger. Although she is a hardcore punk, she works in her office in silence or to the music of Fela Kuti rolling out of her speakers. She is the director of the Lightning Guerrilla festival, but because of her »always black« T-shirts, albedo and focused aggressive approach she sheds some light only through her honest smile that penetrates through her strong red lipstick. She is old school in a way that she prefers making to the point and deeply thought-through work, rather than preparing for a public presentation of it where she prefers to improvise. When she speaks she is cooler than Morgan Freeman. She doesn’t need to remind us who is the boss of the office, however you definitely won’t see her in the morning news in a report on mistreating workers.

Interrogators: present and former members of the editorial board and near and close satellites

What was the alternative and cultural scene in Ljubljana like in the nineties, at the time Stripburger was born?

The scene was very alternative, small, but also very intense. It was a good scene with not as many events as today, which is why every event was interesting, and we attended them all, from concerts, music video screenings … However, there were so few of them that we decided to do the things we were interested in, but could not be found here, ourselves. So we began organizing hard core concerts, we had our own band 2-2-2-7, we were drawing graffiti … After organizing a graffiti exhibition we got the idea for Stripburger magazine which would, as a fanzine, cover all the things we were interested in, namely the entire alternative scene ranging from music to visual arts.

I wasn’t overly excited about the idea at the very beginning since I knew it was a long term project that could stretch into infinity, and I’ve been avoiding larger and more responsible tasks for a long time.

At the time there was this association of organizations called ŠKUC-Forum, with our ŠKD (Students Cultural Association) Forum, which was established in the sixties. I even think it was the first civil association in former Yugoslavia, and word is that it has very deep roots. This Forum had several sections and one of them was Strip Core, which was established in 1989. There was also the club K4, which was run by the FV label. This was an alternative club with different music theme nights, from punk to metal as well as a gay disco, which had an amazing programme, since it was an alternative gay disco, so that’s where we used to go and dance to music. Another sweet spot was the ŠKUC Gallery where they screened music videos from different alternative bands on Saturdays, so we’d go there and after that to the flea market, which represented the highlight of the night (laughs). Radio Študent was also extremely important for us (and others), for this was where we could hear new alternative music (from jazz to hard core) from all over the world. We might have been on the wrong side of the Iron curtain, but we knew more bands than anyone anywhere.

Before Stripburger, you used to manage the hard core band 2-2-2-7. We want to hear a crazy anecdote from those times!

O, shit, I can’t remember anything right now! My memory is fleeting … What was cool about 2-2-2-7 is that it wasn’t just a band, as all band members were creative also in other fields. This was how Stripburger came into existence: the members of the Strip Core collective had their own band, but they also drew, made experimental videos, drew graffiti, etc. All of our creative imagery was made by us or in collaboration with other artists, thus there was no need to hire other people for this. Our concerts also included graffiti as a visual setting and lighting in combination with projections of DK’s photos. They were a visual as well as a musical event.

We toured all across Europe. Our greatest expense was renting a van and almost all of the money went for this. At the time we were the only band in Norway that could and did play eleven concerts in eleven days. Norway was a somewhat weird country in which events only took place on weekends since week days were dedicated to work, so they were shocked when they heard someone wanted to perform during the week. Luckily our contact there was a musician who also organized concerts and was able to convince the venue manager to hold a concert on a working day. He could not believe that we knew more bands than him and he thought we were screwing with him when our singer told him that he had a punk band even before Stiff Little Fingers existed … It was fun driving across those Norwegian mountains where our car windows froze from the inside. When we first arrived we were a bit scared as there was no smoke coming from the roofs of the houses. It was only upon our arrival to Trondheim that we figured out they used electric heating, so of course there was no smoke. We had a really bad previous experience in the Netherlands with their lousy food (we always had to bring our own sausages and ham with us) and their poor heating, so at first we thought that these Norwegians were even wackier than the Dutch and that they didn’t heat their flats at all. In the Netherlands we once slept in the place of one of the organizer’s, and this place had a big hole in the facade of the building because one of his former roommates tried to commit suicide with the kitchen gas cylinder. The cylinder exploded and threw him together with his bed onto the street. He was allegedly OK, which could not be said for the building: a hole remained there. However, this Dutchman with whom we were staying was amazed that we were sitting in his kitchen eating breakfast in our jackets in January, while he was only in his T-shirt.

Tell us more about the Strip Core art collective, how was it founded, why, by whom, who were the members of the collective and how are they connected to the magazine? In short, when did Stripburger start and in what context?

Strip Core is a combination of »strip« (comics) and »hard core«. We found both interesting because at that time they were both very alternative. Comics were considered pulp fiction and hard core was the alternative even in relation to the punk movement. Strip Core was supposed to be the amalgam of both the visual and the musical, while Stripburger was the medium in which we could publish everything that we found interesting at the time. Stripburger stands for »strip« (comics) and »burger« (as in hamburger), and is as such like a sandwich filled with comics (artwork), a feast for both the eyes and the brain. This is clearly visible in the first magazine cover which was made by Jakob Klemenčič and Božo Rakočević from 2-2-2-7, i.e. a joint cover created by two artists. This approach was heavily used also within the magazine, in which the first comic was a sort of a comics jam-session: one artist started the story on one page only for it to be continued by another artist on the next page. As we were penniless it took us two years to raise the funds for printing the first issue which was published only in 1992. A lot of its content became obsolete in the meantime, especially the reviews of photo exhibitions and reports from concerts, so they had to be thrown out of the magazine.

Throughout that period we were also interested in international networking since we never felt connected merely to the Slovenian scene and we certainly did not wish to focus merely on this scene. Especially as the scene was so small you soon started repeating yourself, so we couldn’t focus merely on Slovenian comics. We knew all the hard core bands in the USA, and we also followed the European scene, we were constantly corresponding with various people around the world who created similar things such as musical zines, etc. We had friends all over the world and we considered this to be normal. We were doing things no one else was doing in our country at that time; graffiti, comics, visual arts in general, all connected by hard core music both as a scene and as a way of doing things. So our »schtick« with Strip Core and later Stripburger was that we never had any bosses or editors in chief, but we did everything as equals and together, which is very complicated and time consuming. With the first issue, all the members of Strip Core were considered as editors, there was no editor in chief, while the magazine was assembled and the layout created by Samo Ljubešić, a comics artist himself.

Other members of the collective were Jani Mujič, Božo Rakočević and Dare Kuhar was also very active … Jakob Klemenčič wasn’t exactly a member, but he joined us with the first issue of the magazine – basically anyone could join us. Similar to the band, the Strip Core collective also created different comprehensive presentations of itself, like the one in Ilirska Bistrica and several events in Ljubljana. The publication of the sixth issue of the magazine was accompanied by the presentation of the No brain, no tumors album by 2-2-2-7, by their concert, by a screening of their new music video, by a graffiti exhibition and a Stripburger’s comics exhibition – that was just awesome!

Who were the creators of the magazine at that time? What were their goals and what motivated them to continue with the magazine?

We had a great party after the first issue was published and we also received some feedback, but the editorial team still gave up and shifted the burden onto Boris Baćić who joined us at that time and later on assembled his own editorial team. His role with the magazine was crucial: if it wasn’t for him, the magazine would no longer exist. He completely revised and changed the concept and turned Stripburger into an exclusively comics magazine, so he was the one responsible for its continuation. He established all the contacts with artists from former Yugoslavia, while Jakob Klemenčič, who joined us with the second/third issue, focused on networking with other foreign artists (e.g. Marcel Ruijters). The intent behind the second/third issue was to reconnect the artists from the previously shared cultural space of the former state, since there were no comics magazines at that time in these places. No similar comics fanzines existed at the time, most zines focused on music, activism or literature, so Stripburger was a unique phenomenon of its time. It grew from a very specific sub-cultural scene, but later became independent from it and went its own way.

At the time the magazine didn’t shy away from mainstream comics like it does today, but it was the zine-esque nature of the medium that attracted predominantly alternative artists and this alternative orientation was later followed by the editors who followed. I can mention Jakob Klemenčič, who skipped only one issue, and Matjaž Bertoncelj and Igor Prassel, who were joined by others later on. Each editor left his own mark, but our editorial policy was always collective and followed a general direction. When Boris Baćić left Igor and myself took over the managing of the magazine. I took over the organizational tasks, design and DTP, while Igor wrote a lot of the texts and was very successful at establishing contacts abroad and at the international promotion of the magazine. We all contributed according to our capabilities.

The editorial board has seen many people come and go. There were artists who, for a while, contributed a lot as editors, but later left in order to focus on their creativity once they realized managing a magazine is a complex task that takes up a lot of time. Publishing two issues a year sounds like a rather simple task, but it’s much harder than publishing a translation of a foreign album or publishing an original Slovenian work. With translations you work with the translator and the person who does the lettering, there is very little contact with the artist, as most communication runs through their publisher/agency, usually when you receive or submit the materials. When you work as an editor/publisher with a Slovenian artist, there is a bit more work, but usually you simply receive the work when it’s completed and then you only make slight corrections if necessary. With a magazine you deal with multiple people, you need to have a concept, a vision and constantly come up with new highlights.

So what was the concept of the magazine at the time? How did it fit into the international comics scene?

The founding editors simply wanted to make a comics magazine which happened to be in the fanzine format due to a lack of funds. A comics magazine because we all loved comics, we all read them and because we’ve read everything that was available at that time.

Stripburger was thus a comics magazine that included all sorts of comics. Boris’ idea was to publish everything we could, which meant that the concept was much more inclusive than it is nowadays. For example, today we would not publish 90% of the comics found in Ecoburger. Boris considered it was extremely important to give artists a chance to get published, and he still follows this same principle for his haiku comics and the Apokalipsa magazine: he wants to give everyone a chance. We found this to be problematic with thematic issues, for which we published a public call for submissions and received so many submissions that it was impossible to fit them all into the book. In cases like this you are forced to make a selection. Only later did this selective editorial policy prevail, and this led to higher publication criteria. In the beginning we didn’t have money for a translator or a proof-reader, especially for English, so we developed a kind of Tarzan English of our own with which we communicated with the international audience. We always tried our best to improve the magazine, but we didn’t have the money or staff for all that back then.

Initially, our focus was on reconnecting the comics scene in former Yugoslavia while keeping an interest in the international scene. At that time Stripburger was a peculiarity in the European comics scene. The only comics fanzines or magazines older than Stripburger are probably the Swiss Strapazin, ¡Qué Suerte! by Olaf Ladousse and the Swedish Galago, while all other existing ones are more recent (like for example kuš!). We were always interested in the international environment, we wanted to collaborate with foreign artists, discover new artists, scenes, etc. This was very important to us and even in the early post-socialism period, when borders kept popping up all around us, we transgressed them as if they didn’t exist. In other words, we were »networking« before this became cool and trendy and even before a word existed for such activities. Stripburek is a publication that reveals our passion for discoveries and our tendency to connect. We were pioneers in discovering new artists in former socialist countries and we often published presentations of national scenes and contacts of publishers, comics activists and artists alongside their comics.

Stripburger evolved from a fan-zine into a »pro-zine«, or a fanzine that looks like a professional magazine. Did this also bring with it a change in the concept? What has changed, if anything? What is zine-esque about the magazine, and what is »pro«?

Fanzine-esque is of course our motivation to work with comics, our attitude towards the material, the content and the scene, the DIY approach and low production costs, while the professional part has to do with the technical execution of the magazine, its continuity and steadfastness, and now also with the quality of the featured texts.

We’re still interested in the evolution and development of the comics medium, the exploration and discovery of the new and innovative, networking, the exchange of ideas and the presentation of foreign and domestic artists. The concept did not change much, the main difference is that now we have more funds to cover the production costs, especially printing and postal costs. Content and concept-wise Strip-

burger is still a fanzine, while production-wise it feels professional which means that we can now afford a printing house that is able to print the magazine properly, and we can also pay exhibition fees to the comics artists we exhibit.

You surely must’ve had a moment in your editor’s career when you wanted to give it all up and find a »normal«, boring, but at least less stressful and more lucrative job. What’s your most unpleasant and traumatic experience while managing the magazine?

It’s nice as we have a great team at the moment, but as we do things collectively there are always some interpersonal problems. We don’t always have time for each other, we all do other things as well, we all have our own routines and lives, so if you have other obligations (university, personal life), you aren’t always able to manage it all properly and your colleagues at the magazine also pay that price. Sometimes you might have a problem with your significant other and you end up blaming your colleagues for everything. Some people handle that well, some don’t. Changes in the editorial board can be especially stressful because you need to find someone reliable and willing to work, even if it means for free, like we did at the beginning when no one was paid for their efforts for a very long time. When we were younger we could afford to do this, because we were students and/or living with our parents. Anyway, I still get a headache when I have to go through the same old things all over again.

Meanwhile, as we all know, our biggest problem are the cultural policies and having to deal with them on top of everything. Our input is immensely greater than the input of certain public institutions in which everyone has a nice job, is nicely paid for it and has all the social security that comes from this. It is mind-blowing how the decision-makers, including the Ministry of Culture, have no idea how important this input is and how much this scene contributes to the development of arts, audiences and the general cultural scene in our country. Come to think of it, Stripburger is a synonym for the development of the comics scene in Slovenia. I think we’ve made significant progress over these 25 years and if the soil was more fertile, the progress would have been even greater. If only we didn’t have to handle all of these issues: you solve one, only for another one to come along and you start doubting if it’s worth the effort since it’s often them – the decision-makers, the economy, and similar – who create these problems.

What pushed you into music and later into comics, arts, culture in general? And what inspires you to persist, to stand firmly as the foremost champion of our comics scene? What are the rewards for all your headaches, effort and stress in your activities with Stripburger and in the field of alternative culture in general?

I find it rewarding to be involved in the creative process, producing something and receiving feedback for your work. If only our readers were more communicative in this sense … Ironically we get more feedback from the artists than from the readers, although the artists tend to be more asocial than the others (laughs). To see things happening, to see them changing, meeting new people – these are the main motivations behind my work. If I saw no progress, I would have stopped doing this long ago.

Then the Lighting Guerrilla came around, the festival of light art and light installations. How did this came to see the light of day?

The Lighting Guerrilla festival was born because once again we decided to do something no one was doing here. It’s the same reason that previously led us to bring new hard core bands here or to publish the Strip-

burger magazine. In the beginning our festival was called Detektivi svetlobe (Lighting Detectives) and we had a group of people who worked in lighting design, mostly architects and public-space lighting designers, very few artists among them. One of the exceptions was Aleksandra Stratimirović, my artist friend from Belgrade, living in Sweden, whom I knew from other projects that involved the Belgrade scene. Many of her installations are publicly displayed in Swedish hospitals, schoolyards, courts and other public spaces. The Swedes have a law, which is finally also going to be implemented in Slovenia, which foresees that you have to dedicate 1% of your investment in the public infrastructure to publicly available art. They have a public tender and the artists can present their ideas.

I actually wanted to present her work, but then we decided to make it about the Lighting Detectives. The first festival featured a workshop in which we transformed a subway passage under Zvezda park in Ljubljana, which was overly illuminated in order to fend off the homeless and the drunks, into a place in which one could hang out. We wanted to show how the use of illumination and lighting objects can create a different and interesting space. Later we decided to rename the festival and concentrate on artistic projects. We’ve »stolen« the name Lighting Guerrilla from our Lighting Detectives people who created a series of workshops and interventions for the festival but found this name too aggressive, so they called their activities Light Up Ninja instead. These were one-off lighting interventions: they invited people from a certain neighbourhood to gather in public, light up their flashlights, illuminate something, fly illuminated kites, etc. These people, otherwise architects, didn’t just create megastic professional projects, but they also tried to present the concept of light to common people: housewives, pupils, etc. In our everyday lives we take light for granted, so we tend to forget its meaning. It is only during power cuts that we realize what electricity means to us, how little thought we put into what we can do to make our lives better using light(ing) and all the things we could accomplish with artistic lighting installations in public spaces. This is what Lighting Guerrilla is about.

Could you tell us a bit more about the exhibition of your kidney stone that took place years ago? We find this idea very telling and full of expressiveness, both personally and sociologically …

I consider this kidney stone to be a direct result of the incessant fighting with the cultural politics in Slovenia and I exhibited it in this context, for the title of the exhibition was Cultural politics vs. Art. I took the role of the self-sufficient curator. I found it interesting that the curators are being celebrated as if they were the creators of an exhibition, and the actual artists became (unpaid) subcontractors, although they’re the authors of the exhibited artefacts. In most cases the curators are the only ones who actually get paid, while the artists apparently serve a common good for free. Apart from the fact that cultural politics in Slovenia are unbearable, the exhibition was also inspired by a public tender where you had to have a certain number of previous projects to be eligible to apply, and we lacked a single one. We knew very well that we’d receive only a few pennies for the project, and that we’d need to split the funds or invest them in other, more expensive projects. So I went for a very cheap idea: to exhibit my kidney stone in Kapelica Gallery, which at that time focused on similar body art projects. We had a pedestal with a nice blue velvet cushion and my kidney stone stood illuminated in the middle of it. Next to it you could read my biography with a list of all of my projects, printed on fanfold paper, as well as photos and my medical reports. Afterwards I even toyed with the idea of creating a group exhibition since I knew several artists who had problems with their intestines. We’d have a multimedia exhibition with videos of their stomachs …

Damjan Kocjančič (DK) also took a great photo of this kidney stone that made its way to the cover of the Maska magazine, so I’m really proud of this project (laughs). I was even invited to exhibit it for the European Commission in Brussels by a curator who wanted to organize an entire tour, but I didn’t want to pursue the career of a self-sufficient curator with a single masterpiece (heavy laughs). I hope there won’t be any similar projects in the future.

Who or what is it that gets your blood pumping? Or, in other words, what do you enjoy the most? Is it the fish caught by the »first man in your life«, or is it maybe the fantastic homemade fig marmalade that you cook every year to delight your colleagues at the magazine?

Yes, there is something: it’s called idleness. It’s totally inspiring, and I never seem to get enough of it. A friend once complained how bored he was and I thought »I wish I could be bored from time to time!« Wouldn’t that be awesome? So bored that you really don’t know what to do and can’t think of anything?! No responsibilities, no nothing! Crazy!