Darko Macan (Croatia) – interview, Stripburger 56, December 2011

Who could possibly manage to get away with a triple premeditated comicide? A ‘third-rate’ comic strip artist? A scenarist of American super-blockbusters? An obscure Balkan publisher? Or maybe a ruthless comic strip critic? The answer is: all the above, but only if they are all Darko Macan. With him, we are therefore confronted by a case of a perfect stripocentric, to whom, in addition to the sins listed above, we can add comic-book activism, the editing of a comic-strip magazine, theorising in the media and terrorising the scene in general.

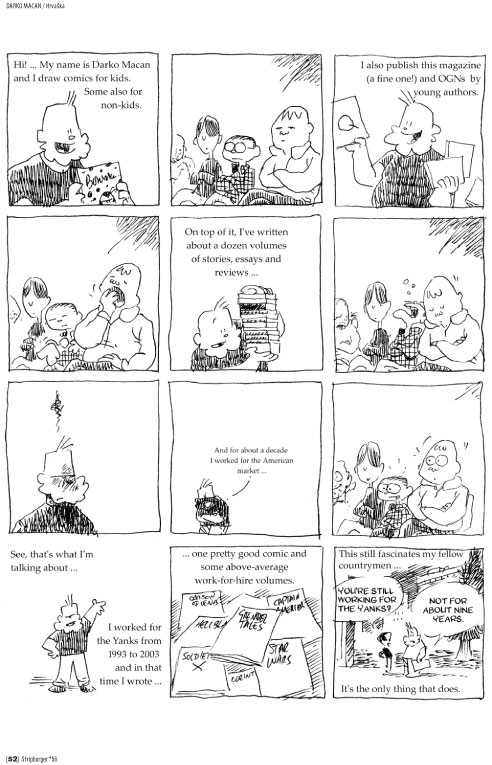

Born in Zagreb in 1966, Darko the stripophile is known to sometimes hide behind the pseudonym of Cecile Quintal. He was schooled as a historian and archaeologist, so his interest in the comic-strip scene of the past is not so surprising. He achieved confirmation with his success in the USA, where he wrote scripts for the Grendel Tales and Star Wars series for Dark Horse Comics. He has worked with eminent limnists of the calibre of Dave Gibbons; he has also sold his art to Disney. Among his most famous Croatian creations we find Borovnica, Sergej, La Bête Noire and Silver City. He writes youth and sci-fi literature, for which he has received repeated awards. In addition, Darko is today an institution on the Croatian comic-strip scene and an impossible-to-ignore personality. The real mystery is how he succeeds, in addition to all that, in finding the time to read any comics.

Darko Macan was interrogated by Gašper Rus and Domen Finžgar Mimo.

What comic book are you reading at the moment, or which one did you read last ?

The comic strip that I look forward to the most these days is Bakuman. It is an online manga, which is published on a weekly basis. I am particularly attracted to the fact that it’s published weekly. When I am informed via the Internet that a new edition has been scanned and published, I immediately go and read it. This feeling is the same to me as when newspapers still used to appear weekly; I always wonder what will happen in the next instalment. This is a rarity for me and that is why this is currently my favourite comic.

The Croatian comics scene, as seen from the Slovenian perspective, seems very fertile; you have a lot of comic book issues and good authors … How do you see it as an insider?

The answer is not simple. When I look at the Slovenian scene, I see everything that I would like to have in Croatia. I am referring to the opuses and the authors of these opuses; which can be appreciated through their albums. You have a much stronger original author scene, with more or less everyone writing their own material. There are exceptions, but in its essence, the scene is original. Croatia has illustrators and publishers. The latter has blossomed in Croatia only in the last five or six years or so. That did not have an effect on the domestic comic strip scene. It is not so much that the publishers would not be ready to publish, but rather that authors who become good then escape abroad to work for money. When I look at the Croatian scene, I never see anything good, I only see what is not good or what I am missing. There isn’t a particular comic which would appeal to readers, the readers are not interested in it… and the result is that in Croatia those who would like to live on their comics go abroad to work for money. This would not be a problem if it happened like in the case of Tomaž Lavrič, who goes onto the French market and produces his own comic books; but these Croatian artists do comic books on commission and make a living out of it, but the comics are not their best products. A whole bunch of Serbian and Croatian artists work abroad as hired labour, selling their ‘hand’ and skills there. I’m not saying that this is bad, but it nevertheless makes me sorry that the situation is the way it is. I don’t see the Croatian scene in such a rosy light as you are describing it, but my view is subjective, from the inside, and marked by trials and failures.

How would you compare comic strip production in the countries of former Yugoslavia today, and in the past in this same region? What differences do you see, if any?

First, I should point out a fact: when Yugoslavia was falling apart, I had just become a pro, so my ‘rosy’ perception of the scene in the former Yuga is that of the reader and the ‘dark’ perception is that of the author. I think the basic point of comparison is the former market of twenty-two million readers. Of course, not everyone actually read comics, but Veliki Blek was still printed in runs of a hundred and twenty thousand copies, Stripoteka in thirty thousand copies, etc. These were the figures which induced the publishers of Dnevnik, Forum, Dečje novine and other papers around the eighties, after twenty years of translating comics, to start investing also in domestic comic strip production. This ended with the economic crisis of the late eighties and the war. In addition – this is my completely subjective observation – up until the eighties, comics were important in the minds of readers. Sure, not everyone was buying them, but many did. After the war, comics started losing their significance. Croatia finds itself on the margins of children’s cartoons, original comic strips that are even less noticeable than children’s comics, and collectors. People used to buy those comic books that they tended to read in the past, for comfort, because they knew what they were going to get. I really don’t intend to accuse readers of anything, but they are not interested in finding new comics, they prefer to know exactly what they will get when they buy a comic book. These are their exact words: when I buy Zagor, I know what I get, I read that and relax. I find this slightly sad, because it is far from my vision of an ideal comic strip reader, who is always looking for something new and fun. Probably the situation is similar with films, when viewers only watch movies within a certain genre, so they do not watch movies that would encourage them to think, but rather watch them purely to relax. These days, the comic strip is less important, but it’s probably the case everywhere. Some ten years ago, Steven Grant said that there was far too much choice for any medium to be a genuine mass medium. In the former Yuga, I would buy about sixteen issues per month (not including Lunov Magnus Strip and other series) out of the thirty or so that were available; they were cheap and it wasn’t impossible to keep track of them. So, everyone was more or less reading the same comics; but today, the choice is unlimited: with the Internet, torrents, the availability of complete filmographies. In the past, if you wanted to see some older film, you had to wait for a certain cycle of films on TV, borrow worn-out videotapes or watch it in the Cinematheque; while these days you can just download any movie or comic book off the Internet, anything whatsoever. Once, we all used to grow up in the same way; while today, each individual is formed in their own way.

While we’re on the subject of the countries of former Yugoslavia: Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia have the most developed comic strip scenes. How do you see the comic strip culture of these countries, and do you think it would be possible to identify any specific characteristics for each of them, which would reflect national identity through the medium of the comic strip?

In terms of identity, I do not think so; ten or fifteen years ago I would have said that Slovenia had an original comic strip scene, Croatia had commercial comics and Serbia had underground comics. Today this is no longer entirely true. In the last eight to ten years, Serbia has exported about forty draughtsmen to western markets (especially to France, as well as a few to the USA), while the underground scene in the country has diminished a bit. Even Zograf is in a way mainstream these days, Wostok and others have diminished a little, they are less prominent in the public eye. In comparison with the others, Croatia probably has a more developed comic book scene for children; but this is not relevant, because it’s kind of a coincidence. Slovenia has the most developed original comic book scene; here there are authors who both write and draw their own albums and have been doing it for many years. In Croatia, someone creates one or two albums and then forgets about it, because the comics do not sell and people do not talk about them, so they either go into other branches of art or start working in the commercial sphere. There are also exceptions: in Croatia, one such case is Danijel Žeželj. He actually had to leave Croatia in order to have a continuous production of his own comics. In Serbia, the best example is probably Zograf, but Serbia has another interesting phenomenon. There were some attempts to create a commercial comic strip scene: from Milan Konjević with his superheroes, through Marko Stojanović with his Vekovnici series, to the guy who puts out the comics fanzine Lavirint that provides entertainment for the whole family. These are all imitations of foreign examples, but it is nevertheless of interest that this is an attempt to overcome the main drawback faced in this part of the world: if someone wants to work on a comic album in his/her spare time, they will spend five years on it. It is basically teamwork: several authors are involved in the same comic strip with each of them only taking over a specific task. While this may leave readers lukewarm in their reactions, it is nevertheless a great way to promote production. The results were not overwhelming. Thanks to their enthusiasm something is still going on, but only time will tell.

As regards Croatia, it is difficult for me to judge what was good and successful and what was not, because I was involved in it all. What I like about Slovenia is this original approach to comic strip albums, and Stripburger, which has been in existence for almost 20 years. This is an enviable tradition, which others are lacking – of course Serbia does have Stripoteka and Politikin Zabavnik, but this is something else. On the subject of the national character: Slovenian comics are the most national, because they deal with concrete issues the most. Zograf’s and Žeželj’s works are intimate self-portraits of their authors; some comics did engage in national issues, but none of that was strongly emphasised (with the exception of some wartime comics).

You are active in many different roles in the world of comics: as a draughtsman, writer, editor, publisher and critic; so we would like to know whether you think this is important and necessary, and in what role you think you can contribute most to Croatian culture?

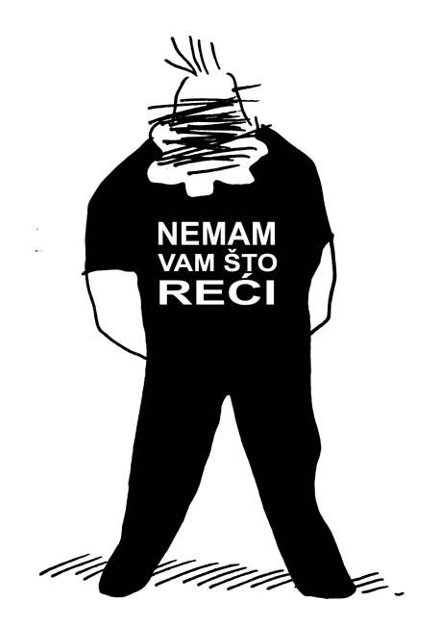

I developed myself as a writer because I perceived the limits of my own drawing abilities and because I wanted to do other things, which turned out to be relatively successful. Between 1993 and 2003 we talked about how it would be if we had a newspaper: we would all work for it, even for free. And then in this void, when nothing was happening at home, I took part of the money that I got from the Americans and spent it on publishing projects. This was exactly ten years too late. In 1993, when we started to talk about it, we had more energy, but in 2003, when it actually materialised, only a few younger artists remained. Others, who had proven their talent abroad, did not have the time to work for the domestic market. Well, Q magazine did not cover its own costs. Each issue sold worse than the previous one and each time it disappointed someone else because they couldn’t find Modesty Blaise or Blueberry in it. When they started to change the conditions of sales and distribution, I withdrew it from the newsstands, because we were no longer making even three hundred euros a month. It all stemmed more out of a desire for something to be going on. The positive effect of this project was that from this corpse emerged first Libellus, then Fibra, and finally More Comics. My mistake was that Q was published in the obsolete format of a comics magazine sold in newsstands, which is my obsession. Others were better than me at feeling the pulse of the audience; they issued reprints of Ken Parker in better-quality editions on better paper, with better binding and printing, and with better translations; everything was done better. Later they published entire French albums. This was what the audience wanted – they did not want a few select comics with fine artwork; they wanted a new, nice, fat, entire story in colour – so, I completely missed the format. Those that were successful after me were those who learned from my mistakes. I think that paradoxically I’m most successful as a translator. When someone praises me, they praise me for my translations. I think I’m quite a good critic, but “fuck critics” … I think at least my comics are not that poorly written, but they don’t receive a more significant response outside of child audiences. In terms of drawing, the most negative criticism on them comes from myself… An anecdote: at this year’s Mafest, I met Iztok Sitar, who got drunk, approached Štef and a group of colleagues and asked him why in the world he would hang out with these second-rate draughtsmen and me – third-rate; and he had a point! As far as my drawing skills go, in terms of their composition, graphic properties and other aspects, my comics really are third-rate, but my characters still work, because they are living characters in a living world. Otherwise, they are not too appealing in terms of drawing; in this I am in agreement with my colleague Sitar.

You mentioned translation and my next question relates to precisely this area. As far as I know, you are currently translating Lavrič’s Red Alert. Language-wise, this is a very sensitive comic strip, so I assume that the task must be quite challenging …

I translated the first part of Lavrič’s comic some seven years ago – while I haven’t yet started on the second – so I don’t remember any concrete problems. When translating, I tend to follow the principle that even in an ideal situation, a reader who does not speak the original language must be able to read a text in translation without ever getting stuck in the process. When the initial parts of Red Alert were published in Q, some readers very much appreciated that they were finally able to read it, because it had previously only been published in Slovenian. This somehow created an interest in Lavrič in the Balkans; he only really began to be read at that time, even though he was already known. Many did not even try to read his comics because they were only available in the Slovenian language. By the way, when I used to sell Stripburger, I always only supplied two copies, because it was always only purchased by the same two people. As if it had been in Chinese…

When I translate a text, I return to it a few times so that all the linguistic structures that do not exist in Croatian get ironed out, and even a few times after assembling it, to see how the translation functions on a specific page. The last time around I do not read the original at all, only the translation, and if something does not work, I substitute it with a more appropriate formulation. Those who read it were pleased. In this manner, the comic strip is halfway to poetry, because it is trying to say as much as possible with a limited number of words. There is more freedom, because the important thing is to achieve the same effect with the readers as with the original and not to make them notice that they are reading a translation.

Speaking of your drawing: even though you are critical towards it, I personally think it is quite ‘correct’ and I have a feeling that there are many comic strip artists with even more modest drawing skills. We have Matjaž Bertoncelj, and on a global scale there is, for example, Scott Adams with his Dilbert. Where does your aversion to your own drawings come from?

This is because I’m a good critic. You observe the others, you see what is not good and then you look at yourself and you cannot say that your work is great. The instinctive defence of anyone who you criticise is: “Look at how you draw yourself”. I don’t want to argue that I criticise them because I think I would be able to perform a certain task better, but because I can see where they are going wrong, like I do with myself. I would correct everything, if only I knew how.

How did my drawings become such as they are? For me, comics are storytelling. Everything I’ve done since I was nine was to tell stories in the most functional manner possible. If this process is exposed through what I draw, then I do not make corrections to it. This is great for telling stories. I learned to do that well, but I neglected some issues of graphism, thickness of the lines, and similar issues. There was a little improvement in those areas, but not much. Finally, I realised that I should have already learned these things twenty years ago, but I had not, and now I cannot do it anymore because it would mean investing a lot of work. So then I devoted my energies to other roles (editing, writing, etc.). When I draw something that is not entirely good, but good enough, then I leave it as it is. Those who draw really well work on various sketches, refine their drawings and don’t abandon them until they are satisfied. It does not seem useful to me to be satisfied with a drawing, perhaps it is better to be dissatisfied. Every single time I draw, I tell myself that I ought to give up drawing and leave it to someone better. There is nothing about drawing that makes me happy, but when the characters come alive on paper, then this is just ‘it’. Objectively, of course, I am better at writing novels, because I have complete control over words, whereas that is not the case with the drawings.

With that, you’ve partly answered my next question. Why do you want to draw some of your own comic books yourself, while with others you entrust them to someone else? Is the reason for this more pragmatic in nature – when there is no one who could draw it for you – or do you think that for some comics you’re the most suitable draughtsman yourself?

Some things are so personal that they either have to be drawn by me or by nobody. Sometimes it’s because it is the quickest way, and sometimes because for me to create comics means to draw comics. I also enjoy collaborations, because they offer something that I would not be able to achieve on my own; but too often it has happened that those collaborations which were not backed up by a publisher with money never materialised. An example is Borovnica, which I drew for nineteen years, and which is a kind of diary of my thoughts and feelings. I once had a block and I asked Dario Kukić for a few sketches, but then it was not Borovnica anymore. In the case of Sergej it is my own masochism, because I want to draw a longer comic myself. Some things are simply best if I draw them myself, because then I do not need to interpret and explain to someone else what I want from a comic. The chief reason remains that I want to draw comics … Perhaps I should learn to draw better, maybe I’m too old, but we’ll see what happens. Evidence in favour of the poor quality of my drawing is that readers generally don’t reach out for my comics. Borovnica, which was published in Modra Lasta, is read because the kids are already familiar with it and know what it is about, but otherwise my comics do not work on the first encounter or at first glance.

Do you usually have the opportunity to choose the artists for collaboration or have you ever been forced into an already fixed tandem?

One and the other, all sorts of things have happened. In Star Wars there was no choice: if I wanted to work, I just had to get a draughtsman, be it a good one or a bad one. With Croatian projects I like that aspect of co-operation, when can I choose who writes what and who draws what. Sometimes you have a great illustrator, with whom you simply do not get on; sometimes you work with people, because you are friends; sometimes because you work well together; sometimes experimentally; at the invitation of other drawers… I realised how many people there are who would like to draw comic books, but do not know how to tackle it. Then they join any kind of team project and work for a few pennies. This is quite fascinating to me.

There are people who are excellent draughtsmen, but very strenuous to work with; while others are not so good, but you can see that they go beyond themselves in their work, because it feels good to them to be involved in it, and this can also be seen in the comic strip. The opposite example can be seen in those comics of Lavrič that he drew himself, in comparison with those which he drew based on Frank Giroud’s or David Morvan’s scenarios. The latter do not have that inspiration, despite the skill that they manifest, they lack that playfulness which is characteristic for the comics that Lavrič writes himself.

Take the project on which I worked with Radovanović. I did not expect to ever finish even the first episode. But when I saw how he tried, how he gave back more than I had invested in the first place, it gave me the momentum for a new episode. For me, such moments are the best thing about creating comics in collaboration, when the authors encourage each other to work better.

Could you mention some of your more successful collaborations with draughtsmen and is there an illustrator with whom you would really want to work, but there hasn’t yet been an opportunity?

Including the living AND the dead?

The living.

If you just consider with whom I have worked more than once, it is clear who my favourites are. One just cannot compete with the dead. Take, for example, Edvin Biuković: the first illustrator with whom I worked – the results were impressive. Then Igor Kordej: with him I very much liked the results, but the work process was slightly different from the one with Edvin. Of course, I was flattered to work with him because I grew up on his comics. A similar example is Štef Bartolić, whose ideas were more concrete than Kordej’s, but he loves to debate for hours on end before undertaking any kind of work. Then I can mention Goran Sudžuka, with whom I worked on Martina Mjesec and Svebor i Plamena. I was very pleased with the results of my cooperation with Robert Solanović on Mister Mačak, until we fell out and now we no longer work together. The only project that wasn’t done for the money was La Bête Noire with Milan Jovanović. This project is very dear to me; hopefully this year it will come out in a compilation. If I worked with someone at least twice, it means that I obviously like them. I like the progress that David Petrina made, with whom I collaborated on Ukleti Vitez.

Sometimes I just do not find the work process suitable, it depends. Problems can arise when I like an author too much, and then I adjust to something that that author does anyway, and this is bad. Maybe I’m too much of a ‘fanboy’ and I like to know who is going to draw, because in doing so it is easier for me to imagine the scenes. For example, Tomaž Lavrič: I would really like to collaborate with him, but I’m not entirely convinced that we would not fall out, since we disagree about certain matters. But also because I see how it is when he works with others. I think it’s best when he works on his own stuff. In principle, I find it easiest when illustrators choose me by themselves and tell me what they want me to do. Then you know that they want to work with you, and you do not need to convince them of this or that.

Thought experiment: I’d love to work with Moebius, but then I would write stuff that would be too similar to what he has already worked on, and he would then draw something to my text, something that would be worse than what he had already drawn before. Being such an incorrigible ‘fanboy’ is a major obstacle to my authorship, because it means that I am putting myself in a subordinate position. Therefore, I am best at working with someone from my own generation, with whom I am in an equivalent position.

Recently you organised the first so-called 24-hour cartoon drawing of the former Yuga (drawing of a completed comic strip on 24 pages in 24 hours), following the inspiration of Scott McCloud. Could you tell us more about this experience?

Historically speaking, this was actually the third such drawing. The first was in Belgrade, while the second was a private drawing in Croatia, completely unrelated to the first one. In Croatia there is a whole bunch of new authors that create only occasionally, on the Internet, on blogs, and that draw comics purely for their own entertainment, without any professional ambitions. These people are gathering around my blog and other related projects.

I like this 24-hour drawing, I’ve also participated several times in Angoulême. This time I wanted to have a comic strip event on the premises of the Zagreb Academy in order to bring comic strips closer to the cultural mainstream. Then Ines Krasić from the Academy joined in, arranged a space for us; Vlado Šagadin helped with food and in general. At the end, this project turned out to be the smallest failure out of everything I have worked on. We all had a lot of fun, the following issue of Q was twice the usual thickness because of the comics from this drawing session. It was a truly positive experience. Maybe because I had very low expectations.

As you can see, I don’t have many original ideas. I’m not a pioneer, an innovator or a genius, who would invent something completely new, but I am good at spotting a good idea somewhere else and using it here. This is why I have been working in this area, while my ideas are taken from some other environments and circumstances, and have therefore not always functioned optimally. This 24-hour drawing session was organised practically overnight and Fabijan Črneka set up a website for downloading comics literally overnight.

You seem to like projects that are somehow formalistic in their nature. Another project we could consider in this group is Max Jaguar. Can you explain what this project is about and where you see the utility and potential of such experiments?

The comic strip is conditioned by the format in which it is created; be it newspaper, book, manga or bande dessinée …

These comics are therefore not the same. The rhythm is different and the storytelling requirements are different. I am interested in these formats and want to test each one I come across. I love these commitments and constraints. When I was presented with a 160 page notebook, I set myself the goal to create a comic book diary, one page for each day. The format of the comic book was already determined by the format of the notebook, and the format is what gives a form to what you’ve already got in your mind, ideas are not a problem at all. My blog brings together people who only draw every now and then, or as a hobby, and some new kids who want to work, so I launched a few initiatives. Regoč was the first comic strip in which I put down a page without text. Someone wrote the text for it and drew a new page without text. Then someone else entered their own text and drew a new page and so on. It went on for twenty weeks, and we were joined by two people who had only appeared for the purpose of this project. The next project involved creating a comic book starting with the last picture and moving back towards the first. Max Jaguar started with a banner that was once drawn by Milan Jovanović, and is being manufactured in a similar fashion to Regoč.

Each of these projects has attracted some authors who had not worked in comics before. I do not know why, but the fact that people choose to expose themselves and say ‘I will do it’ cannot be bad. They may get infected with this virus and continue to work in this sphere. Drawing is solitary work, so people like to draw at jam sessions in order to feel less lonely. When someone enters the world of comics, he/she is usually warmly welcomed and accepted. Of course there are also arseholes among those entering the scene, as well as there being arseholes already in it, so that not all is brilliant, but when someone comes along with a little bit of talent, you welcome him/her; no matter how long you’ve been working in this area, you’re ours. This is due to our childlike unconcern and enthusiasm, these games may yet serve some purpose, and if someone learns something in the process as well, so much the better.

Somewhere I have come across your statement that “the only real comic strip is the genre comic strip”. I find this an interesting position, so I would like to know if you still think that way, and if so, why?

On the one hand, I can say that this is not true; on the other hand, the comic strip that would once not have been considered as “genre” (such as the comics published by L’Association in France), maybe really is just ‘a new genre’. I guess the idea is that the genre comic strip is the one that creates habitual readers. There are those who read only Zagor for consolation or for some other reason; but in modern comics the same is happening as in modern literature. Someone likes reading books by a certain author, but this does not necessarily mean that this person would read any other literature. The comic strip has become a literary genre, which is assessed according to different criteria than in the past. When I was a kid, comics were considered literature for boys. These were genre comic strips and they created a habit through subsequent episodes. I still think that a comic book that can be published in episodes (and still work fine as such) is something exceptional. As, for example, Trondheim’s Lapinot; something that is built from album to album, which can go on for as much as a decade. The form of the series represents an in-depth friendship with comics and this should not be ignored. Of course I myself love authors’ series the best. Serial comics are very important and ‘serialisation’ is something which the comic strip does very well. There is no need for everyone now to be making graphic novels, it is merely what’s fashionable at the moment.

Science fiction plays an important role in your opus, while on the other hand, in one of your essays you state that this is a genre that quickly becomes obsolete. What, then, is it that keeps your faith in this genre and why are you so fond of it?

The fact is that I am already a bit fed-up with science fiction and that as a reader I am now finding that it is not offering me much any more. Production is huge, but within the genre not much is new, so I am not such a fan anymore. I see this category more as philosophy than literature, as it informs your way of thinking. My way of thinking about the world is science fiction. I find it easier to think through this metaphor than through strict realism. The latter otherwise attracts me, but the world in my head is most likely not very realistic; there’s science fiction working in conjunction with the present. The golden age for science fiction is twelve: at that age it hits you straight in the head, but as literature it’s not very convincing.

It is also a perishable genre, because there is nothing that spoils faster than the future; but I still like it, although I don’t read it much. When I write, I find it easier to manage worlds in which I have no restrictions.

Would you be able give us an example of a good SF comic strip for adults, one that doesn’t underestimate the reader?

Hmmm, Lapinot has elements of science fiction, but people do not tend to regard it as science fiction. The seventies were the golden age of science fiction and all of my favourite SF comics are from that era (The Cosmic Travellers, Aster Blistok and others). Macchu Pichu is a fine example of domestic comics of this kind.

It is hard to talk about competition if you write SF yourself. In the comics scene in general, this has a relatively small presence. In Spirou we have it almost all the time, even Tintin possesses elements of science fiction … I also like everything by Jodorowsky, including the Metabarons. I think it is a very good space saga. Let’s say that The Metabarons is a good example of science fiction with a rating of B+.

We have already mentioned your essays. In one of them, you wrote that comic book heroes affected your moral maturation and that some of the comic heroes of your youth are still your role models. On the other hand, it seems like your own characters are often rather cynical and are not quite morally exemplary (such as Borovnica and Mišo). Why this discrepancy?

Life tends to make one a little bitter, and I do not know if my favourite characters really did affect me, but I know where the impact of comics on my life actually shows. For many years I behaved in such a way that when I was right, I thought I had the right to take it out on other people, shout at them or hit them, because they were behaving in a way that I thought was wrong. That’s just the way it works in comics: when the heroes of comic strips are right, they attack the comic book villain and this is never called into question. In real life you get strange looks from people if you act that way, so obviously I wasn’t the best in making a distinction between reality and comic books. Perhaps my aggression and other kinds of foolishness are expressed through my comic strip heroes. The other day Tico told me that Borovnica is no longer intelligent, but has instead become evil and is getting worse and worse. He has been colouring it for a long time and knows it very well. The older I get, the more I get irritated with the world and the less I believe that it is going to get better. Therefore, I perhaps take revenge on the world through my characters.

I remember one of the comics on your blog, in which you settle the score with your ‘discarded’ characters. Can an author of comic books love his own heroes in the way he loves the heroes of other authors?

You like other people’s heroes in a way that is more pure, while you love your own more like the way you love your family members. When you become a comic strip author, you start to see other people’s characters in a different way, not just in terms of what happened to them this time, but how the author drew them, how he developed the plot, etc. You can no longer be neutral. In contrast, your own ‘mob’ is alive. That settling of accounts with them is due to my exasperation at the realisation that these characters were in a kind of limbo, because the author had stopped drawing them. This irritated me, so I decided to kill them to get rid of them, but then I’ve also had to resurrect some from the dead because there has been a commission, etc. This is a reflection of my state of consciousness at that time. I drew the comics without a pre-prepared script, like a diary, almost without a pencil, and at the time it felt good. The responses of the people who read this and did not know those characters before were interesting, but there was another interesting thing, something I found rather bizarre. Jaspis, one of the characters, otherwise a holy-fool, came across the main villain and a real sadist in this comic strip, surprising me with this unexpected development. He showed me that characters, when in the company of their fellows, somehow stratify; some become more good, some more sinister, others show some unknown traits: that is what I found the most interesting.

I notice that many of your characters are anthropomorphic animals (Sergej, Mišo, Mister Mačak) – which in the world of comics is not at all uncommon. In your opinion, why are animal figures sometimes thought more appropriate than ordinary people?

Trondheim said they are more symbolic or something, but comics with animal characters are for most of us among the first things we read (Tom and Jerry, Donald Duck). I take what I like, I like a stylised and witty drawing, and these have often been just such characters. Sergej was created in response to Usagi Yojimbo, so I wanted to give it a try. Mišo was the main character in some educational material on IT, but was then launched overnight in the context of another contract, and was indirectly inspired by Lavrič’s Diareja. Mister Mačak is the creation of Robert Solanović, while the Kljunovi came from some of his other drawings. The trick is that it brings an automatic characterisation; you see a cat, and you already think something about this character. In any case, let the illustrators draw what they feel like or what suits them most.

We know that in addition to writing comics you also write prose. At what stage do you decide whether an idea will be developed into a comic book or a story in prose?

Sad, but true: I think I decide that immediately. When I get an idea, it depends on what led me to it. If it is a response to a comic strip, it is automatically in the form of comics and the same is true for prose. This is part of the dialogue with the seen and read. Some critics say that art should reflect life, but I think it is was Anatole France who said that the painter does not paint the tree because he saw a tree, but because he saw another painter painting a tree.

Thus, art talks with itself and this is what comes out of it. One of the problems that I find most disturbing about myself, is that patterns of how others worked on a comic book are too strong a presence in my mind. I cannot escape from comics which refer to comics. In prose, it is a little easier; there my style is already developed, while in the comic strip my fanboy side bursts out, which is too aware of what has already been created: it has been informed by too much reading and is too tied to the already seen. For each of my own comics, I can say in response to what it has occurred; the same applies to its form. Then I comfort myself by the fact that, either way, I’m using a language that has already been invented by someone else.

How do you see the development of contemporary comics and do you miss anything in them?

I think the original author comic strip got to the point where it wanted to get to, i.e. it became equivalent to other media. It succeeded in that, as there is no topic that cannot be treated in comic strip form. Today the trend is to make comics with a story that could also be told through another medium. A good example is the biography of Man Ray’s model Lulu de Montparnasse, which I read and I did not find a single reason why this would not rather be a prose work.

I miss the old fashioned comic strip, that beautiful old one, in episodes, but it is just I that misses it. When there still weren’t many graphic novels around, they were all praised by default, then some others got praised out of all proportion, e.g. Stuck Rubber Baby, or even Blankets, where everything is empty. Comics and literature critics praised many works purely because they were dealing with a specific serious issue. This flood will have a positive effect because there will be someone who will say: “This is good, this is not good”; because a critical vocabulary will finally emerge. Therefore, I will not read just any Sacco, because I am interested in what happened in Bosnia, but not, let’s say, in Palestine. Fortunately, these days cartoonists are no longer limited to drawing comics for children against their will; such comics are now mostly drawn by those who really want this.

What’s going on with the Q comics? What is the current situation and what are the prospects for the future?

Q is my big defeat. First I wanted to do a commercial magazine, but this fell through with the first issue. We then discovered the option of obtaining the support of the Ministry of Culture and the thing started to flourish. Up to the fifteenth edition we were unable to reverse the declining sales until they changed the distribution and sales conditions. Q therefore had to be removed from the newsstands and that was the moment of my defeat. Until that point I tried to learn from some successful solutions from abroad, but then we got a generation that focused the magazine more on the domestic comic strip scene, which only worsened the sales. Then I was inspired by Stripburger’s model and began publishing albums that were presented to the ministry as regular issues of the magazine. Some got sold, some did not, but my enthusiasm is currently quite low. I need a new idea, to bring the project back to life again.

The comic strip has for some time now been expanding into the digital world (Internet, e-books), but it seems that it has not yet fully adapted to these new media. How do you see the development of comics in the digital environment, in which direction could it develop?

I’m a very bad visionary, and this question contains two separate issues. The first is comic strips on the Internet as a “creative outlet”: last year, they counted a million comics that were either found on the Internet or had been made for the Internet. This is the reality: paper does not mean anything to these authors since they started drawing comics because they read comics first on the Internet. It is a complete change of authorial paradigm. The other thing is publishing and the e-book: this is linked with money and is not so relevant. It will work if readers adopt it. Some things do work. American comics and manga in particular are an excellent on-screen read, while this is less true for European variants; some of this is due to their compactness, some because of the ‘scrolling’, some because the French do not know how to scan. The economic model (or the method of sale and distribution) is otherwise not connected with the medium. If this turns out to be worthwhile, we will all be on the Internet tomorrow, otherwise not. In principle, I am a bad economist and if I ever earn anything, it is just a coincidence. There are a million comics on the Internet; so it seems that comics as such apparently did survive, while I am getting old and dying off.

What can you tell us about your future plans – what do you still want to accomplish in comics? A utopian project maybe? What do you still see as a challenge in comics?

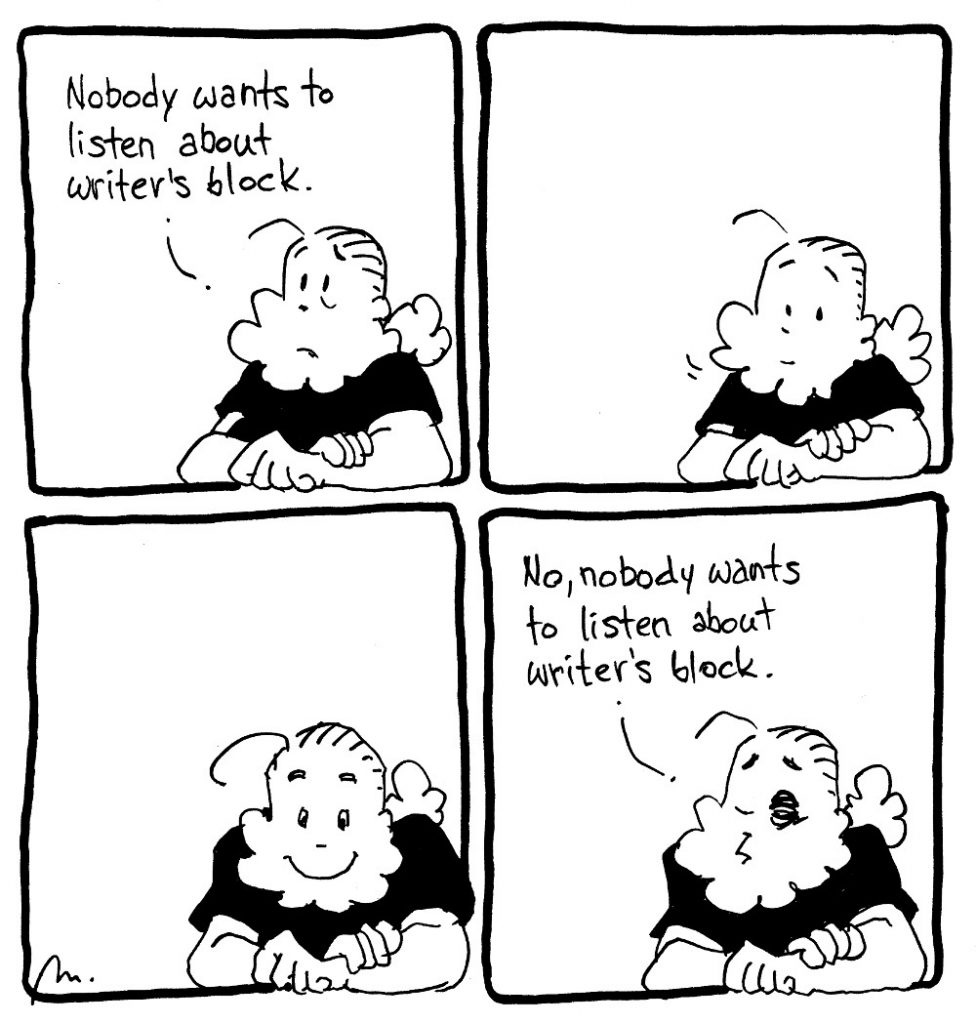

In the last week I killed three comics, stopped creating them and thought about what I would really like to finish. One of these is Sergej. There is still half of it missing, so two hundred and fifty pages, I would like to expedite and complete that. Borovnica has already had five books and I do not have anything to add there. Some things are still tempting me and I wonder whether they can be realised. One is the history of Croatia in comic strip form, not too serious, but spiced with humour. I am tired, now I think more about what to avoid, rather than what new thing to burden myself with. Maybe something between Dnevniq and Obračun, so essays on comics in a comic strip format, but the thing should be comprehensive and well thought through.

This issue of Stripburger is dedicated to recipes. What do you recommend to young people, as well as other comic strip authors? What must they consider on their career paths, what is the recipe for success or failure in comics?

There is no recipe for that, as success is defined by each individual for him/herself. If someone sets himself a goal to create a comic strip the way he conceived it himself, and realises it, he has succeeded. It is sad that I have always implemented everything I ever wanted. Maybe I aimed too low. If you set too high a goal, you will be happy for a longer time.

How to write a good comic strip review? How does this differ from other reviews? How to tackle reviewing a comic strip which is generally bad?

The time of uncontested praise for comics is over; the comic strip is an adult, no longer a newborn. With regard to daily newspapers and readers who don’t read comics, it’s like that: it would be best to select a comic strip with something good in it, and speak well about it, too. If you do not have anything good to say about a comic strip, you should remain silent. When it comes to online press and reading material that is read by comics readers and connoisseurs, then you can start firing from all cannons. A good critic should establish the necessary criteria; in the first place, craft-skill criteria (how is it drawn, how can it be read), and secondly the critic should discover what the author intended to portray and compare that with what was actually achieved.

You know that Stripburger also has a collection called Ambasada Strip. In it we try not to publish only classics that have stood the test of time, but also works that are likely to receive a good response on the domestic scene, which could sell well and which people would read … With this in mind, do you have any suggestions as to what we could also publish?

That I cannot answer, because I have tried to do that for the Croats with Q magazine, but no one bought it. You do not have a new Muster, who would produce a series for the wider audience, and that would not quite suit Stripburger’s profile. Stripburger is not exactly easy to read, I read it because it is the antidote to my way of thinking. I need to see how it is possible to think differently from the way that I think. Stripburger has this problem, which is not just its own particularity – which is the short story format. The short form is mainly used by young authors and the topics that they deal with are always the same. When the generations change, this is followed by variations on the same theme.

That is also why literature prefers longer genres, like the novel; while in the comic book world, this is equivalent to the form of the album. The short story is not a form that many people would claim to adore, and it is more difficult to make as well. Stripburger survived three or four changes of editorial teams and has become an institution. It succeeded in that because its idea is what coalesces any respective team. Therefore, the individual “parts” are replaceable. This aspect of long-time publication and remaining current is great.

We talked about Sergej. Can you explain what type of story this really is and who is Sergej?

The only references to Usagi Yojimbo are the American format and the anthropomorphised animals. Sergej was conceived as a series, but I found that that doesn’t always suit me, and that I love things that end. Thus, Sergej became a post-apocalyptic novel. When I want to drive people away, I tell them that this is a comic book on the role of the individual in historic processes. It does have a number of flaws, but it also has all the characteristics that make up a novel, and I owe it to myself to finish it, even if the final assessment may not be exactly flattering.

What about the young Croatian comic strip authors? Which of them are, in your opinion, the most talented and promising?

These are more or less female illustrators. Namely, Sonja Gašperov, Sara Divjak, Irena Jukić and Dunja Janković. These are girls who create their own comic books. Currently, they are much better and stronger than the boys. One exception is Maksim Šimić, who could become a good commercial illustrator, while others are so far more on the borderline between being amateurs and professionals. Ivan Marušić produces good novels in a comic strip form, but he insists on a drawing-style that is not particularly accessible at first glance. The aforementioned authors are, so far, the best that the Croatian comic strip scene can offer. I can also mention Josip Sršen, my long-time apprentice, who got independent and is proving my adage that one can make it in comics with persistence.