Marijan Pušavec (Slovenia) – interview, Stripburger 67, June 2016

Everyone who is familiar with the greatest achievements of the domestic comics production knows Marijan Pušavec. Together with Zoran Smiljanić they have been creating the extensive historical narrative Meksinajnarji for quite a while now. As if that wasn’t enough to place him on the Slovenian comics Parnassus, Pušavec raised the comics-writing standards even higher.

Together with Jakob Klemenčič, a seasoned comics veteran, they created a comics biography of the (not so) famous and (under)appreciated Slovenian traveller and novelist Alma Maksimilijana Karlin. The book was published at the end of last year and has stirred a huge interest amongst readers, thus a detailed interview with the writer was inevitable. We asked him a lot of questions, and he answered even more. Enjoy.

[Bojan Albahari]

How did you come up with the idea for the biographical graphic novel about Alma Maksimilijana Karlin? Who else contributed and helped in the making of the book?

It was my idea to write and draw the biography of this famous, but unappreciated citizen of the world from Celje, an individual unparalleled in the Slovenian cultural space. Alma’s story has been presented in practically all art forms: it has been staged as a theatre monodrama, a dance performance (twice), been presented in two documentaries, a nice monograph, and has also inspired a number of other artistic performances … As a researcher of her life and work, I wasn’t too pleased with these representations, I felt a comprehensive presentation of her peculiar – even for today’s terms modern sensibility and life style – was direly needed. I see this presentation as an arch between the incredible insight she had, shown primarily in her testimonial works, and the 8-year long adventure around the world, unsurpassed even today. As I have said many times before, her real biography exceeds the imagination of great movie screenwriters. Since no feature movie about Alma is on the horizon, I decided to create a biographical graphic novel.

Accepting the fact that I am never going to write her literary biography, I opted for the easier option and decided to tell her story through a comic: images and text made it easy to convey Alma’s complexity to a wider audience. This decision stemmed from my belief in the communication power of comics in the contemporary world in which images trump over words. Comics vehemently combine and merge images and words, appealing to the reader’s ‘less thinking, more looking’ laziness, thus enabling a comprehensive experience that peaks when a good story meets an appropriate visual expression. Ultimately, there aren’t many biographical graphic novels like this, especially in our country.

The first and main collaborator was, of course, Jakob Klemenčič, an excellent artist who has been fascinating me with his comics, and who sometimes made me angry, if I felt he was lagging behind in his work. I checked whether Klemenčič was right for my idea with my old friend Zoran Smiljanić, whom I trust, and Sandi Buh, who has a great overview of Slovenian comics artists. None of them advised me against him, and Jakob was also quickly persuaded to join me.

How hard (or easy) was it to work with Jakob? What was your greatest motivation during your collaboration?

Jakob Klemenčič is a conscientious, precise, know-ledgeable, sensitive, hardworking taskmaster, who speaks foreign languages, reads books, uses his head and is a very benevolent person … which writer wouldn’t want to work with an artist like that? Due to his broad mental horizon and artistic range I knew that I could not allow myself any writer’s shortcuts or other type of carelessness. I was afraid that he wouldn’t draw them and he would start having an even worse opinion of me as a writer. There was certain selfishness in our creative relationship, but it was always in the service of the greater good. This was why I rarely tried to intervene in his drawings, and I did so only when truly nece-ssary – for example when we had a misunderstanding as to how my (or Alma’s) words should look like.

Drawing ‘Alma’ took three long years. What about the scenario? Was it already written, or did you write it as you went along? How did the writing take place?

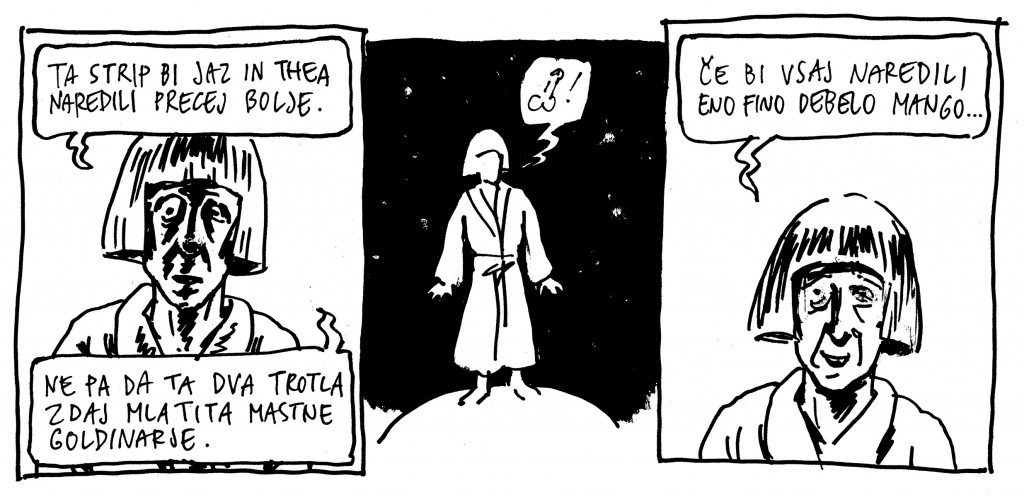

Before Jakob and I met for the first time in Celje to discuss the book, and the distinguished artist excitedly breathed his ‘I do’, I only had a prologue to the story in my head, an emotional accent that was supposed to run throughout the book (I later yielded to Jakob and let him add an explanation to the final laughter of the mother and daughter). I waited for him to draw these six pages and I was terrified: this prologue was so po-werful I feared its power would overshadow the rest. But then I realized I had the ‘right person’ on my side. Only after that point did I begin to truly consider how I would capture Alma’s life in words. I instantly decided she would be the narrator of her life, which she would narrate in her own words, thoughts, formulations and articulations. Jakob and I decided to divide the story into four chapters and a prologue. In spite of Jakob’s unwillingness, I insisted on including an epilogue, which clarified Thea’s fate. Of course, he was reluctant to do it because he was already fed up with the two women at the time… as a compromise we created an epilogue on two instead of four or five pages.

The first two chapters were quickly completed, while the third was the most time consuming one. Jakob started drawing the fourth in the middle, thus Alma died before she joined the Yugoslav resistance. He was very understanding while haunting me for texts and waiting for new scenes, knowing that it’s hard to tell a story you know too much about. This was probably my main handicap, until I managed to relax by asking “What would Alma think?”

My main intention was to pass on Alma’s life story with her own words, and avoid glorifying her, something I have noticed was often done in the works about her by the self-styled guardians of her legacy. I must confess I regard myself as one of them, but I’ve never succumbed to the temptation to appropriate her or her lore in any way, or to declare my story to be the only worthwhile one. I derive great pleasure from falsifying all kinds of nonsense and myths about Alma.

In practice, the scenario was written in the following way: first I figured out the concept and asked Jakob’s approval. Then I took all Alma’s testimonial works and I cut out, pasted and filled the passages and texts that fit my concept. What I could not find in the books, I found in the fragments of her legacy: in her correspondence with Thea, in newspaper articles by and about her, and in Thea’s unpublished autobiography. Then I decided which quotes and texts needed to appear in a certain scene, and described the space, time and atmosphere Jakob had to draw. When I had a clear picture of how a certain scene should look like, I wrote it all down as instructions for Jakob, who employed my solutions if he didn’t have a better idea. He diligently sent back individual pages before inking them, and took into account my suggestions whenever he found them appropriate. We never quarrelled about this.

How did you set about researching the life and work of Alma M. Karlin?

I’ve been researching Alma M. Karlin for roughly fifteen years. I started around the beginning of the millennium, when Goga Stefanović Erjavec, a choreographer from Celje, staged Angel on Earth, a dance performance dedicated to Alma. After the show, there was a public debate in Celje about the fate of the abandoned and desolate house on Pečovnik, where Alma died in 1950 and her companion Thea Schreiber Gammelin lived until her death in 1988.

At the same time, a local businessman demolished an old mountain lodge on the nearby hill of Svetina and constructed a megalomaniac ‘Alma’s home’, named after this world traveller buried in a cemetery in the vicinity, so that he would make it more commercially recognisable and successful. The self-styled guardians of Alma’s legacy went berserk because they thought this was a disrespectful appropriation of the name of a Nobel Prize candidate. This was when I started paying attention to the polemic: a Nobel Prize candidate from Celje?

I began reading expert, semi-expert and journalistic texts on Alma. There wasn’t much material, and the basic facts differed from text to text. It became clear that this woman has so far not been given a proper place in the national cultural heritage. I was so angered by the numerous enthusiastic ‘researchers’ who attributed Alma with more than what was true, that I delved into this myth and struggled through her legacy (mainly stored in the manuscript section of the National University Library) and the (still dishevelled and unreviewed) legacy of her partner Thea. During this research I encountered unexpected things, such as the fact that the first part of her travelogue Samotno potovanje (Lonely journey), that was first published in Slovene language as late as 1969 (published in German in 1929, catapulting her into the European literary orbit of the period), was not translated in its entirety, while the high point of my research was the discovery of her never published autobiography. I managed to convince the publishing house Mohorjeva družba to re-publish and re- translate the ‘Lonely journey’, and the translator Mateja Ajdnik Korošec to translate and finance Alma’s autobiography. In the meantime I created a virtual online space for Alma that provides authentic basic information and visual material about her life and work.

What is your stance towards her now? Did it change in any way? What do you think of her now? Would you portray her differently today?

My opinion on Alma has changed considerably over the years. At first, I looked down upon her, probably because of the idolizing by her followers, who more or less perpetuated the same nonsense that was beginning to be perceived as the truth, and because I didn’t have a very good opinion about her fiction. After discovering her autobiography entitled Sama/Ein Mensch wird (By myself), I realized there was no better work about the coming of age of a woman in our little Slovenian province at the break of the century. Mind you, her autobiography was also written in German, just as her other books.

If I would make a graphic novel about her again, it wouldn’t be any different. Now, after the third reprint, I might want to change an emphasis or accentuate an experience that is not visible or present enough. I’m still convinced that this unique woman is a good thing to have happened to the Slovenian people, even though these people, as history has shown us, don’t know how to treat such excellence. In this sense it’s yet another sad Slovenian provincial story.

Conspiracy theorists vehemently assert that the choice of Alma MAKSIMILIJANA Karlin is not a coincidence: she shares her middle name with the Austrian Mexican imperator you’ve covered in Meksikajnarji. Let’s clear this once and for all: is this true?

Yes, there is definitely something in this. Especially as both scenarios were in the making at the same time, and on one of her travels along the west Mexican coast Alma met a descendant of one of these ‘meksikajnarji’ (‘meksikajnarji’ were volunteers who travelled to Mexico in 1864 to fight for emperor Maxi-

milian, the brother of the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph). This was Jakob’s discovery as he used to wander those places years ago. I’m sure there is indeed a metaphysical connection between Alma and Max that Alma’s theosophical followers, who believe in the migration of souls and the transfer of the personal soul onto the global one, would be able to substantiate. Namely, if we follow the conspiracy theory, Ferdinand Maximilian did not meet his demise on the outskirts of Queretaro in 1867. Instead he survived, set up a new identity somewhere in Latin America, and continued to live in Arequipa – which happened to be Alma’s first stop on her journey around the world – until his old age.

You and Zoran Smiljanić have a long and fruitful cooperation, for you co-created the longest Slovenian comics story Meksikajnarji. How did this occur?

This is a long and old story. We both love westerns in all their manifestations, and we both love Mexico in all its manifestations, but we don’t like Slovenians in all their manifestations. When we learned about this interesting episode of Slovenian history, we were fascinated by it, but we soon forgot all about it. In the beginning of the 1990s Zoran went on a ‘study’ trip to Mexico, and after that families and kids happened, then I moved to Celje, then we did individual projects, all until my friend Zoran suggested: “Shall we do this?” So we did. Since we were both writers of the scenario, we independently wrote our own drafts with the characters and main events, and then put together the two drafts. We picked the most promising ideas, and agreed upon the development of the adventure and the characters in this epic. After numerous meetings, long discussions, deliberations, researching sources Zoran started to draw the first part eleven years ago, and I began writing texts and dialogues. Finally, we both polished the results until we both found them pleasing and convincing. The working process hasn’t changed in all these years, although we have reached a point in our routine where we can save time and avoid bad mood, which is most often caused by my delays in the submission of the texts.

How come you moved from conventional literature to script-writing for comics? Who or what drew you to this (pun intended)? Why are you so attracted to comics? The potential of the medium, examples of good practice or something else?

I wouldn’t agree that I’ve moved from literature to scriptwriting. To be honest, I don’t see myself as a writer or a scriptwriter, even though I would say I can do both fairly well. Both art forms strive to tell a story. In order to achieve this they use the narrative, and I have always understood stories as an important instrument of experiencing and understanding the world, in the same way myths were used to explain the world in antiquity. I think comics are just one of the numerous forms that can be used to tell stories. I think comics have an advantage over literature for they contain concrete images that can either open and expand (in the best case scenario) the reader’s perception or narrow (ideologically or poetically) and even define it (in the worst case scenario). I also see comics as something between literature and movies. They’re more dynamic than literature, and if they had sounds … uff, they would become movies. After all, a lot of movi-es were based on (massively popular) comics. And there’s another thing that draws me to comics: their potentially subversive potential that can be expressed without words, in just a few images (corresponding to aphorisms, anecdotes and jokes in literature). And of course humour in all its manifestations that I find lacking in literature, especially Slovene. Of course, there is no shortage of good comics examples abroad, and, luckily, also in Slovenia.

Apart from the comics scenarios, you’ve written short prose and articles on literature, and you have graduated on Witold Gombrowicz’s work. Would you be interested in comics even if you hadn’t studied comparative literature?

I knew about comics when I wasn’t even able to read: my dad used to read them in the toilet and I loved to leaf through them on the bench behind the kitchen stove. I’ve upgraded this activity by enjoying full-length animated movies that were usually based on famous works of literature. I think it is safe to say I’d be interested in comics regardless of my education, since I’ve only learned about the study of comparative literature right before graduating from high school.

What do comics represent to you personally? Which ones do you read or you’ve read? How did your education in comics take place? Who are your role models, if you have any? Whom do you consider an excellent comics writer and why?

In my opinion comics are equivalent to literature. Of course this does not apply to every single comic, and I do have my favourite genres, especially adventurous ‘realistic’ comics with a lot of history, with a tight story and prominent heroes/antiheroes. I also like erotic comics, but above all I enjoy reading comics that feature atmospheric artwork, comics in which the artist uses minimalist expression to appeal to my emotions and trigger an experience that I’m familiar with from literature and movies. Usually I tend to watch them rather than read them. I dislike comics that would fall within the fantasy genre in literature.

When it comes to comics, I’m totally self-taught. The greatest contribution to my comics education came from my friend Zoran, with whom we share the same sensibility towards the world. I have no role models in these terms, and I don’t really know enough about the comics world to be able to highlight an individual artist. But I do admire an all round author, i.e. a writer and artist in the same person.

By now you’ve gained a good amount of experience in comics writing. How do you see the work of a comics writer now? What are the main challenges in this field? What is most important and what is the hardest?

Hmm, I can only speak from my own experience, I don’t have a theoretical basis or reflection on it. As I’m no good at drawing, but I am able to think situation-wise and event-wise (two fundamental postulates of narration), I judge comics only in the second step, the first one being the experience itself. If the experience is strong in itself, I don’t necessarily take the next step. The second step is about how the individual elements are coordinated, so the reader is struck by the work as a whole. Sometimes it bothers me when the artwork surpasses a poor or even really bad narrative, or the other way around, when great story material is drawn too hurriedly or even hackneyed. Sometimes I’m angry with all round authors who create a hardly digestible mess from perfectly good material … Anyway, I find it is important to maintain a balance of the artwork, the narrative approach and the message, and this is what I think is the hardest to achieve. I’m increasingly becoming convinced that two people are necessary in order to achieve this.

As regards content, I think that it’s not really of primary importance: if the aforementioned balance is present, and a recognizable author’s perspective – expressed in an individualistic way – is added to it, then I can enjoy an excellent comic that pleases me in all respects, even when it comes to some poetic bucolics or urban bizarreness.

I believe that the main challenges for a good comics scenario are the same as the ones in movies: a good story, convincing dialogues, characters that give life to these dialogues, and a credible theme that elicits the reader’s/viewer’s experience.

What are you plans for the future as regards co-mics? We heard that you are already working on some projects with other Slovene artists. What are you working on?

We’re finishing the last scenes of Meksikajnarji. Zoran and I feel a moral and human debt towards Toni Mrlak, the helicopter pilot who was shot down over Rožna Dolina in Ljubljana on 27th June 1991. I’m also preparing a series on the deeds and former inhabitants of the village of Koritnikovo for Martin Ramoveš, who, I think, has great comics potential. In the future, I’d love to co-create an erotic comic, spiced with Slovenian bizarre particularities, and I’m also tempted to create a ‘political’ comic in a much more grotesque expressive manner than the Hardfuckers. I also find the experiment that they are performing at Radio Študent, with their audio comics / sound comics, very intriguing.

Drawings: Jakob Klemenčič (Alma M. Karlin: A Cosmopolitan from the Province)