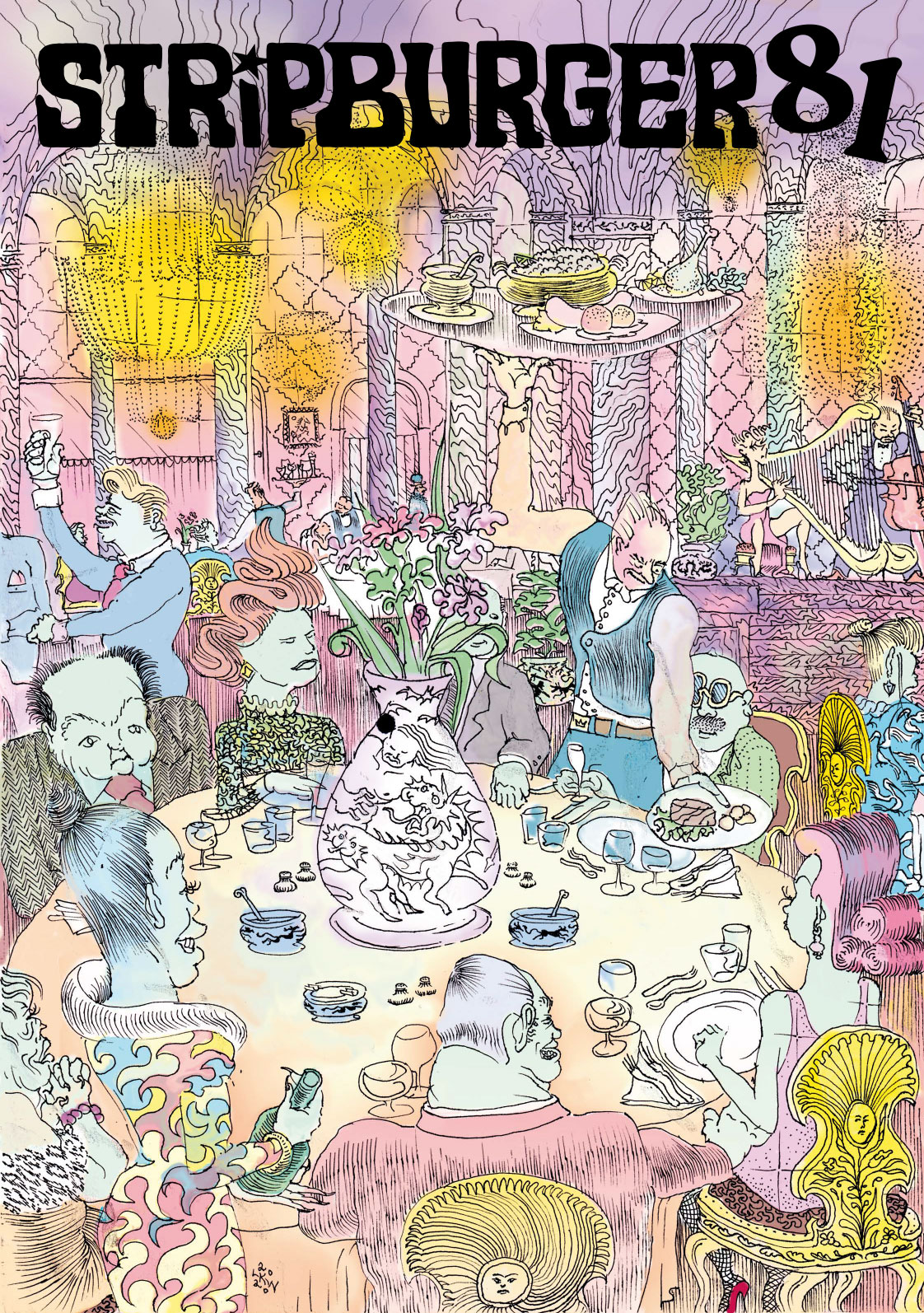

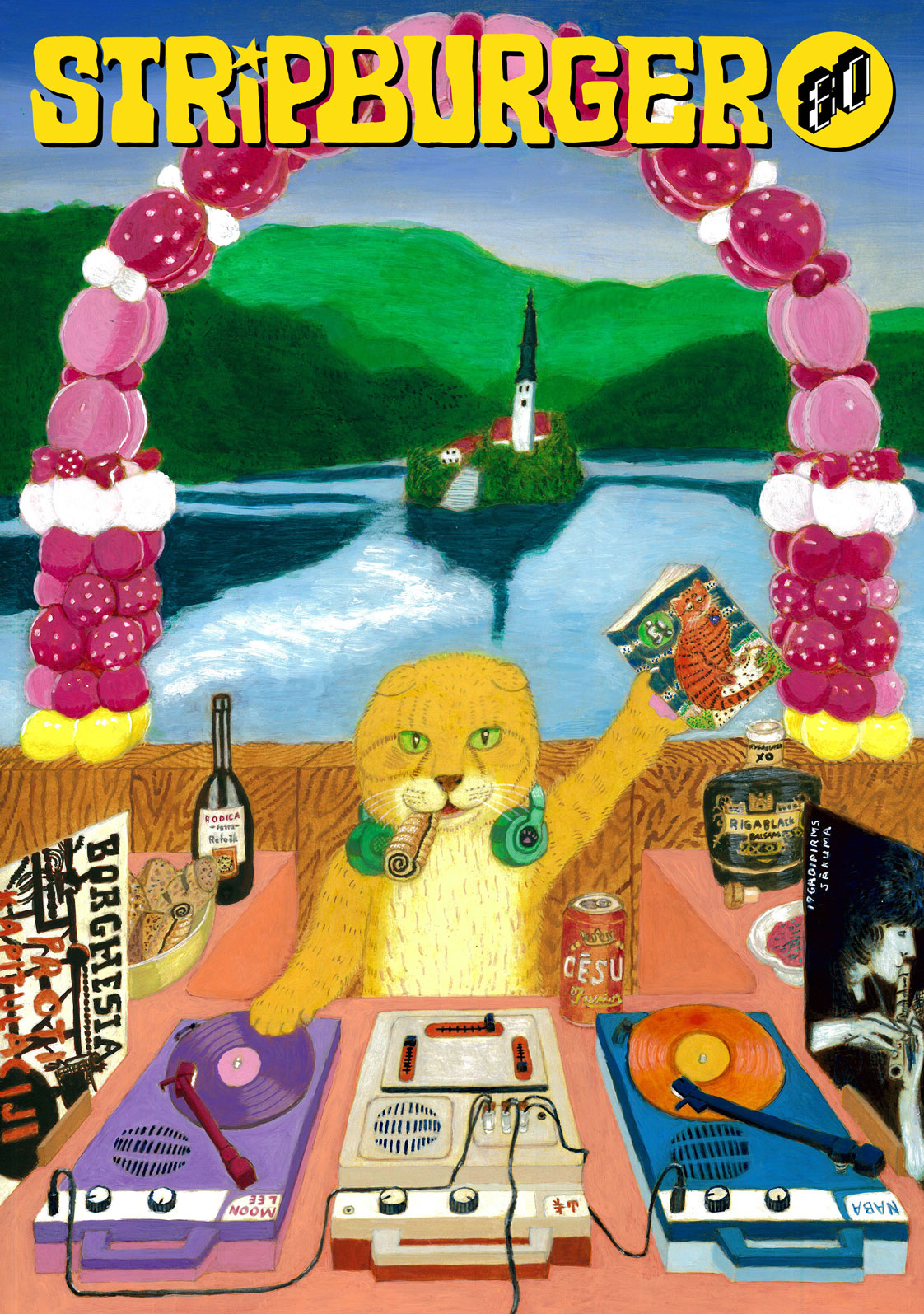

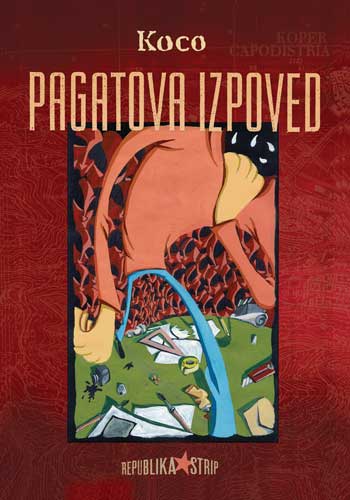

Koco’s name is closely linked to Stripburger. With years-long editing and publishing, he left a distinctive mark on the magazine. Readers remember him by his spontaneous, sometimes awkward, but always interesting comics. In addition to drawing and painting, he has a passion towards animation and teaching. The back cover of this Stripburger issue features one of his works. He participated in group exhibitions in Ljubljana, Athens, Stocholm,Berlin, Belgrade and Paris.

Matej Kocjan – KOCO: comic strip author, illustrator, teacher, animator

Four years ago you moved from Ljubljana to Povir. Are you enjoying the countryside life?

Ljubljana is a great city. But at the same time tiring. Every city has its own pace with which it pressures you. You quickly get tangled in repetitive patterns and relations, which often turn out to be pointless and a complete waist of time. There is a bunch of unimportant meetings and you are often being dragged from one part of the town to the other. This rhythm was beginning to drown me. I believe that as time goes on, it begins to eat away all of us.

Living in Ljubljana cost me a lot of energy, and although it was not easy, it felt good to move back to Littoral.

I have detached myself from a closed scene where all you hear is constant whining. You get fed up with it. People usually complain in order to have something to talk about.

Your album Pagatova izpoved (Pagat’s Confession) is closely connected to the city life.

Among other things, yes. At the time, I was dealing with a personal crisis, brought upon by other factors too. During the period, I didn’t draw, because it would ware me out too much. I did keep a journal though, which I used as a starting point later on.

I had other ideas, but at that time, this particular one seemed the most innovative and, in a way, I was still feeling the mood, which has passed now, but it seems to me, that the timing was right. Soon after, when I began working on the album, I was offered to work as a substitute. This is why I didn’t have the time to finish my album. That kind of project obviously demands its share of time.

Comic strip album is hard work. It’s probably important to finish it in a given period which should not be too long, so you don’t lose your focus.

When I began working on the album, I had no concept of integrity. The contents seemed powerful and I had the urge to depict them. I started drawing nebulous dreams I had experienced during my crisis period. Later on, those nightmares were a starting point for building events that explained them. Otherwise, all that is detached from my experiences of that time. The album features one enormous construction, and it’s an autobiographical story only in part. At the time, Matjaz Bertoncelj offered a great deal of support to me by advising me on dramaturgy.

Generally speaking, a graphical solution usually works in comic strips, but it can lead to a loss of contents.

When I began making comic strips, I loved experimenting and I was interested in many techniques, which of course always took a toll on the contents. At the time I didn’t have an appropriate appreciation for my work. As many beginners, I was impatient. I started to work on it quickly, and I quickly finished it.

How has work at Stripburger, where you spent a great deal of time, helped you in the making of comic strips?

Coming to Stripburger felt like an enlightenment to me. Before that, I was only familiar with Bonelli’s comics, Mickey Mouse and Muster’s Twisted-Tail (Zvitorepec). At Stripburger I discovered the underground works. At the time, the comic strip history was a terra incognita to me. It took me approximately two years to figure out, which authors of the Stripburger library are important.

I loved the Stripburger team that was interested in the same things as I was. I could share views, problems I encountered while working, all in all, it was great. What a great experience. As time went on, I became a permanent member of the editorial board and I began to work on exhibitions, the magazine and everything connected to it.

It turns out I learned a lot from the strip authors that worked for the Mladina weekly. I still have a collection of torn out pages, featuring Smiljanič’s, Lavrič’s and Kastelic’s comics. They have raised my awareness of the comic strip world as far back as in the 80’s.

What kind of feedback do you receive from published works?

The problem with feedback (any kind of feedback) is that it means a lot when the work is new and has just been published. If delayed, the energy is lost and, in fact, you don’t need it anymore. On the other hand, there is a great satisfaction in the fact that your work has been published. But that can be a double-edged sword. The mere fact of publishing does not in itself reflect quality. But surely, I would not have made such a difference in comic strips if my work hadn’t been published, even the work I today consider to be complete crap.

Copyright work is, in general, not as appreciated as it used to be.

There is an abundance of artists as well as copyright works (and even more to come). They are usually chosen according to one particular pattern, just because no one bothers to check out what else is out there, namely the work of quality. We all make the same mistakes. Even I took some things as bad quality, when in fact they were not; this I know today, but at the time they seemed poorly made and simplistic.

What is the main problem of Slovene comic strip? We have already mentioned this.

I don’t know what the problem is with our generation. Maybe the fact that we didn’t read enough when we were young. Maybe we did, but we weren’t able to use it the right way later on. And now we are all learning.

Let’s talk about the subject of your last comic. Superkanta is reminiscent of Alan Ford’s Superciuk.

Exactly! I never read Alan Ford. I had no idea there even was a character named Superciuk (meaning something along the lines of “Superdrunk”). Any resemblance to actual events is therefor coincidental!

The superhero was a result of an association to a drunk Slovene, while the situation itself coresponds to actual events and will do so in the future. At least I hope so. I never desired formations, destined only to produce stories that would entertain readers. I always strived to experiment with the media, dialogues, texts on a given subject. I never wanted to entertain just for the sake of entertainment.

Subjects of a copyright work are usually heavily marked by the author.

I have to say that I am still very fond of the dreamy, absurd world, where things are distorted, but multilayered at the same time. They can be interpreted at different levels and even this symbolism of meanings, which I sometimes use, is very important to me. This is done by not being litteral, by attempting to blur the message and give it more than one meaning when possible. At times it reaches the point of opacity not understandable to anyone, ha ha. I then picture myself as a poor, misunderstood and miserable Calimero. I have to admit that I myself don’t understand the commentaries anymore and that the things I do are opaque and difficult to understand, because I feel I am still evolving and changing.

That is your signature style.

This is one thing that separates me from the professionals. I act as an amateur with the desire to become a professional one day. It seems that the desire is greater than the talent …

You have attempted to work on The Baptism by the Savica (Krst pri Savici), The Goat Devours the Tailor and Shits Him Out. We know you are interested in Slav mythology.

That’s true. It’s a part of our identity that has been left behind and cannot be awaken by modern generations. When I was little, my grandmother from Hrastovlje, used to tell me tales about the dead who, in a funny way, came to life, about witches and gypsies, humans with dog’s heads … Even though the stories were peculiar and frightening at first glance, I enjoyed them a lot, because she was the only one who could tell them that way. When I began studying literature on Slav mythology many years later, it soon became clear to me that it had been reduced to oral tradition, and that there were no materail remnants left behind. Oral tradition from the Istria region was assembled by the author Marjan Tomšič in his book The night is mine, the day is yours that I simply devoured in elementary scool. The stories make your head spin, but most of them are unknown. To the average Slovene, Istria is a mere turistic whore, seducing him with its charms and giving itself away. He can only see its most attractive parts, oblivious of the existence of a different, more continental Istria, rich in oral tradition, where you can always find someone to speak to about things long forgotten. This realm of Slav myths and local adaptations is incredible. It would be great if these traditions were assembled while there still exists someone to tell them. Such material would be a great basis for visual interpretation in the form of animation or comic.

You illustrate for Sobotna priloga, a supplement to the daily Delo.

I started working for Sobotna priloga at a delicate period. I sent my portfolio at the time, when Ervin Milharčič was still the editor-in-chief.

They showed some interest for my work back then, but it was the new editor who invited me to join their team.

Several illustrators stopped publishing in Sobotna priloga. How many are working there now?

In fact, I am the only one. A part of the team quit as a sign of protest and some hadn’t been invited to continue their work with the supplement.

What sort of texts do you illustrate for?

I don’t have much choice. They usually send me texts regarding the educational system, because they know I’m a teacher.

At the very beginning I made it clear that I am not interested in illustrating political texts. I prefer abstract themes, without any defined personalities. This allows the subnote of my illustration to become more visible.

And if you are given a text with which you don’t agree?

I counter it with my illustration and make my position clear. The editorial board was afraid of responses to some illustrations, that were clearly a provocation. But there were no problems. In this case the board acted fairly.

You have to work fast, usually finish by the next morning. Is that a problem?

That type of work suits me. The next morning, I have other engagements, say my family and school.

There is something else that is problematic. I miss a clear vision concearning illustration and comics in most Slovene newspapers. There are foreign papers that for example publish only illustrations, or rather illustrated texts. To me, this seems to be a good and interesting concept with which you can grasp the multilayer effect of a particular content. Photography has a more documentary role and is in a way limited in expression.

We don’t have enough newspaper illustration tradition. Illustration is often used only when there are no suitable photographs. The catch is that photography is cheaper. Photographers are in general underpayed per published photo.

What is absurd is that comics are payed less than illustrations.

To conclude, are you really preparing a new album?

I have gathered some ideas about which I don’t want to talk about untill developped. The problem is in time. Family takes your energy and time that you used to spend on drawing. Once you start, you work days and nights, and so for months at a time. We are talking about elaborate projects that demand consistency and time. Now that I have my usual projects, I often get screwed by the extra ones, and so it happens I get behind on my schedule.