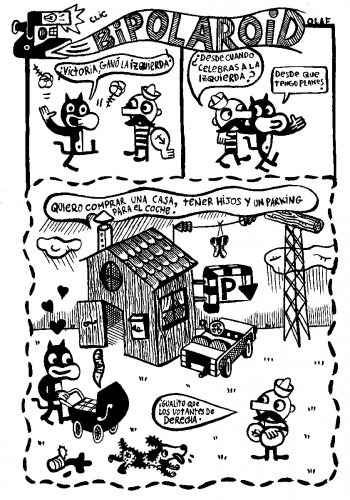

Olaf Ladousse (Spain) – interview, Stripburger 66, December 2015

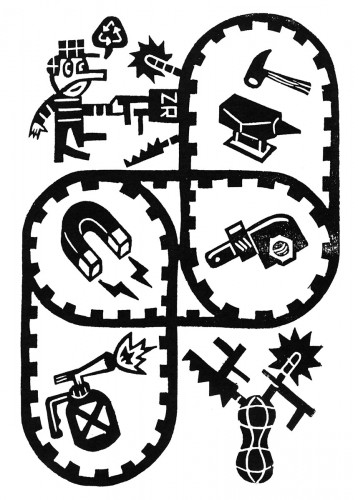

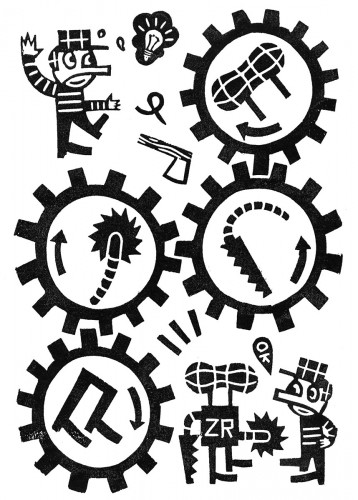

Olaf Ladousse is a ‘one of a kind’. This charmer with a franco-spanish accent is much more than one could imagine by merely reading his comics – although hints there are telling enough. This hardened veteran of the zine scene harbours a strong love for music as well. In his work, it crosses the boundaries of its own art and flows into the visual. And the opposite is true as well: he expresses the ‘uncomicsable’ through musical experimentation with instruments of his own (re)making. His trademark works are linocuts for all purposes: as illustrations, as posters, as comics or many other things. He’s held a linocut workshop in Ljubljana after the opening of his exhibition, where he (and Carmen Espina) also held two musical performances.

We’ve caught him during the preparations for the arrival to Ljubljana and made sure it was really him. Here’s how.

(Albahari)

First of all, we would like to find out more about you, your education, your background and your more or less humble beginnings. You seem to assume a different character in every interview. Who are you now? How and why did you start creating comics (and other forms of art)? How did your professional path evolve? Did you have any doubts, ups and downs?

In my first reincarnation I was a fish, or to be more precise, a salmon, which is why my parents called me Olaf – as a homage to a famous and tasty smoked salmon brand. A long time ago, as I was swimming upstream the Sava River in search of my origins, I bumped into the Argonauts’ boat. I had an argument with Jason about who had the right of way – the one on the surface or the one under the water – the rule wasn’t certain but I can declare with certainty that his crew consisted of a mix of women, horses and fish similar to me. This mixed community gave birth to the dragons that annoyed Saint George so much that he decided to fight them. Don’t worry, I wouldn’t lie to you.

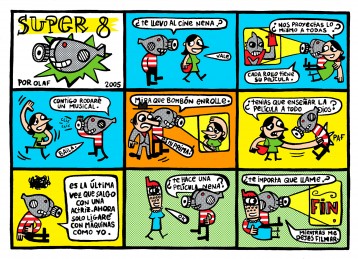

I learned to read and write in school, at the age of 6. Before that I used to draw like any other kid and I still remain to do so. Once I finished with my school, I started spraying stencils all over the neighbourhood. This delinquent activity introduced me to industrial design. I was strangely admitted to a selective public school where I presented my stencils as a book, years before Banksy became famous. I will take advantage of this interview to confirm that I am not him. After 5 years of learning how to shape cool objects and handling machines and a 1 year student exchange at a Mexico University I graduated and left for Madrid. I thought this would be a good place to find new opportunities and plan my return to Latin America. It was not. I started showing my designer book around agencies where I met a lot of unpublished comics artists. I had no job but I had a perfect agenda to start a fanzine. Madrid is not a good place for an industrial designer so I decided to become an illustrator and created the ¡Qué Suerte! fanzine, which means “what luck!”, as I am certain I am a lucky man with only ups.

Comics readers know you best from your zine entitled ¡Qué Suerte! How did it emerge? How long have you been publishing it? How do you manage to produce it with all the other stuff you do? What is the (main) reason you have been doing it for so long? Who (and how) is helping you with it?

My main occupation is being busy inventing a job for myself. Upon my arrival in Spain publishing was my first activity. ¡Qué Suerte! started in 1992, soon after I started rehearsing with the all-girl band Las Solex. Since then I have published one issue of the fanzine every year and changed bands every 13 years. Now is the turn for circuit-bent music with an all-horse combo: LCDD. This bi-polar venture draws the main line that keeps me trapped and famous in the underground scene. My agnostic militancy allows me to explore the flea market on Sundays while the rest are praying on their knees. This lack of faith gives me the freedom and time to staple, bend and shape zines and weird objects such as the doorag instruments and compose LCDD melodies. Thanks to the international collaborators of ¡Qué Suerte! I’m in touch with the graphic scene throughout the underground. I receive nice comics, good drawings, cool letters … Each issue seems to please the contributors and our small audience. This is a good reason to keep on publishing. Right now I’m taking advantage of the irreplaceable support of my girlfriend, who is helping me answer the questions in this interview and plan our concerts. But I fold millions of Xerox copies singlehandedly while sipping from a glass of beer and listening to sweet music in the background.

You also create music. Even more, in one of your interviews you said that music is more important to you than comics/images. Can you explain this? Why do you draw (or cut) then?

It is very hard to pay the rent with notes and melodies; it’s easier to find a client for an illustration. As long as I get paid I am happy to draw whatever. But I don’t hand out a license for my music if I am not applauded. Luckily my linocuts are more successful than my records. I consider drawing to be a language with which I communicate and music a medium with which I unleash my emotions. I’m very sentimental and my sentiments are very noisy.

You are not the only comics artist to also create music (or the other way around). We have a similar artist in our redaction (Domen Finžgar), and we also know of Matthias Lehmann (who also creates linocuts), Robert Crumb, Tom Morello, Rob Zombie, Amanda Palmer, Jim Steranko and even David Lynch for example. What do you find so interesting in these two very different media? What are the main challenges of creating music alongside sequential art?

I work at home and host a huge vinyl collection. After breakfast the turntable plays constantly; it is the last thing we turn off at night. At home I wired the computer loudspeaker to my hi-fi through the antenna system, so I no longer have a TV, but I can listen to my records while I am connected to the virtual world. I listen to music while drawing, lino-cutting, printing, cooking … it doesn’t disturb my recipes. The only time I need silence is when I’m reading. There might be a certain empathy between graphic and musical languages, but it seems this does not exist between letters and notes. I play the hardest records while drawing, I pretend I am not paying attention to the sophisticated, strange or unusual sounds, for my brain seems to be better at assimilating new things this way. I recommend this exercise while listening to LCDD music. I met Matthias Lehmann only once in Paris, and I agree that he is better than me at engraving and playing the guitar (I highly recommend his Raw Death album with the Le Dernier Cri screen-printed cover) but I’m objectively cuter than him. Robert Crumb and I share the obsession for records that are to be played at 78 RPM, while David Lynch and I share the haircut and nothing of his mystical philosophy. I hope I’ll soon have the opportunity to meet Domen Finžgar and see if he’s prettier than Matthias.

Your restless creativity led you to invent the doorags. Could you tell us more about them, how you came up with the idea for them and how do you make them? What’s the idea behind them?

As you might have noticed I don’t believe in God, however, I’m a fervent follower of the sole rule of DIY: “do it yourself”. I needed to take out the sounds from toys so that I could include them in my music. The easiest way to do this was to plug them directly into the amplifier. Then I discovered I could modulate the sounds by changing or altering some parts of the electronic circuit. All of this took place at the same time as I met Thermos Malling from the Doorag duo and following the advice of Fela Borbone, the engineer of the Ulan Bator Trio. This was a good occasion for practicing my industrial designer skills. The circuit-bending scene happens to be largely international: the people from Asia have all the coolest toys at hand, the English-speaking have the main literature on bending, while the people from the third world have the tradition of recycling home-made devices. This is the main reason behind LCDD’s obsession to tour the world. I don’t believe everybody digs the music, but there is always an audience that will appreciate the process.

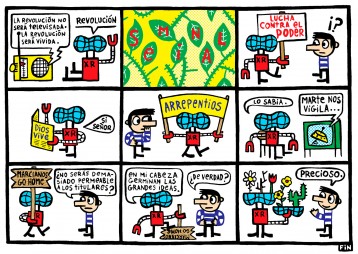

What is the story with you and El Cartel? How did that collaboration emerge? What is its purpose?

There was a fascist newspaper called La Voz de España (Spain’s Voice) which was stuck to the walls throughout Madrid. I was annoyed to see people reading it. I decided to create a poster with the street issue of ¡Qué Suerte! and pasted it over La Voz de España. A few years later a friend proposed to take over the idea as a regular newspaper and this was how El Cartel was born. There were four of us, all press illustrators, we choose the topic, produced and pasted the posters together. We made around 50. They are now compiled in a self-edited book.

So you make posters, but also album covers for indie music label publishers. They both seem to work in a similar way, but posters are ‘public art’, while album covers are usually ‘read’ at home. Does this mean you apply different approaches when you’re making a new design/ illustration?

El Cartel was not a public art matter. It was all about politics. The record covers are packaging. The two attempt to attract your attention in different ways. The record cover has to fit with the sounds and the taste of the band, while the posters were an expression of a personal opinion, we did not need to satisfy any clients with them.

We have noticed a revival in the popularity of basic graphic techniques (linocuts, silkscreen printing, etc). What is the appeal of these techniques for you (and in general)?

There was a time during which we all had to learn how to design with a computer because of the final art requirements. Now that we are all IT experts we know enough to look for different technologies in order to escape from Photoshop filters. Water screen-printing ink made the technique easier, but I am not sure engraving is as popular. My sister is the real professional illustrator in the family; she sent me my first painting tubes. Later she told me I should cut linoleum as my manual skills were better than my drawings. I agreed to do so, but only if she let me choose my own colours this time. I’m too proud to go the gym, but my age and physical condition require exercise, an activity I fulfill while printing on the floor with a kitchen roller, a DIY way to do sit-ups while listening to Cecil Taylor instead of Lady Gaga.

Do you have an unfulfilled artistic wish? What would you create if you had the means to do it?

Do I have unfulfilled wishes? I told you, I’m a lucky man. If you gave me a lot of money, the opportunity and the energy I might shoot a nice European movie, the kind they hate in America and love in Asia. For €1,000 I can make a new neon light.

What will your next project be?

I came to Ljubljana to learn the recipe for ‘burek’ for I would like to open the first ‘burek’ restaurant for hipsters in my trendy gentrified neighbourhood. Currently you can get a ginger and green tea ice-cream with an Ethiopian fixed-gear espresso, but there’s no spinach ‘burek’. In between I hope to produce some more fanzines and tour Africa.

SHORT BIOGRAPHY

Olaf Ladousse (1967, Paris) is a hyperactive explorer of visual and musical arts who lives in Madrid. His work is characterized by his DIY approach. His illustrations are regularly published in different Spanish and foreign printed media. He’s the publisher of one of the oldest graphic/comics zines titled ¡Qué Suerte! and a member of the graphic association El Cartel. Apart from his visual art, he also creates custom neon lights and ‘doorags’ (one-of-a-kind instruments made of toys and other apparati). He co-founded the musical band Los Caballos de Düsseldorf (LCDD) that often performs during silent movie screenings and other occasions.